It was a chaplain who designed one of history’s first specialized amphibious assault ships. With it, the crusaders of the Fifth Crusade (1217–21 AD) were able to capture the sea tower (or “chain tower,” in Arabic, Burj as-Silsilah) guarding the easternmost mouth of the Nile and, eventually, take the triple-walled city of Damietta, today a metropolis of more than a million people.

Oliver and the Ships

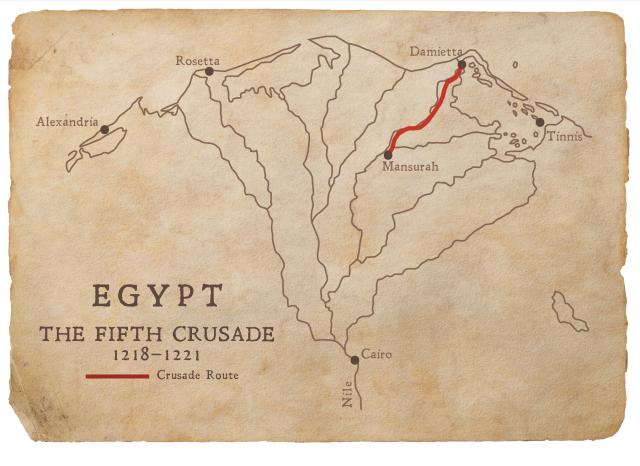

Hoping to trade territory captured in Egypt for Saracen- (Muslim-) controlled Jerusalem, the Fifth crusaders sailed from the Levant to Damietta, a bustling commercial city more highly valued by their enemies. Among the arriving crusaders was the clergyman Oliver of Cologne—more often known as Oliver of Paderborn as in later life he became bishop in that German city.

Oliver was a scholasticus, today, roughly equivalent to a Jesuit professor at a Roman Catholic–sponsored university, who became chaplain to the Frisian and Westphalian contingent of crusaders. At papal request, Oliver had traveled throughout northwest Germany preaching crusade and recruiting troops. He was a popular leader even without an operational role, and he used his eloquence to convince others of the wisdom of the plan to assault Damietta, first conceived by John of Brienne, the military (but not political) leader of the crusaders. He also wrote a chronicle of the crusade, in which he downplays his own activities, but he evidently was brave and a natural engineer.

Like all the other crusaders, Oliver sailed to Damietta in a “cog,” the standard merchant vessel of the time. Sometimes used as troop transports and supply ships, cogs also could function as artillery platforms—using archers, ballistae, and catapults—in sieges against cities, achieving best effect in coordination with land forces.

There was no standard design for cogs, which ranged from 30 to 200 tons burden, although there were a few in the 300–1,000-ton range. Dimensions could range from 49 to 82 feet in length with a beam of 16 to 26 feet. These are estimates based on medieval documents, as well as carvings and official seals; building plans did not survive, and only three partially preserved cogs have been discovered in sediment or river silt, the first in 1962. Cogs were propelled by a single square-rigged sail, and versions from northern Europe were clinker- (or lapstrake-) built, in which the hull planks are overlapped.

Cogs could be equipped with castle-like wooden structures on both their broad bows and sterns to protect archers and other fighters in battle. Presumably, such was the configuration of the cog fleet that sailed to Damietta.

Exactly how many crusader ships sailed to Damietta is uncertain. However, the Frisian contingent alone was reported as having 80 ships. Perhaps as many as 200 crusader ships made the relatively short voyage (in comparison to the travel from Germany). It is probable that Oliver sailed with his Frisian comrades in the first wave to reach Egypt. They made landfall on 27 May 1218.

Objective and Enemy

To assault Damietta—with its triple series of high land and sea walls—was a daunting task. With one wall on the edge of the east bank of the Nile and another on Lake Manzaleh, the Saracen defenders considered the approaches to the city limited as it would be difficult for shipborne forces to breach the sea-facing walls. However, amphibious forces could use the river to land on the opposite (west) bank of the Nile out of range of the city’s defenders—although they obviously would still need to cross to the other bank. Another option was to attack the city from the east by sailing on Lake Manzaleh.

Today, at 544 square miles, Manzaleh is roughly 80 percent smaller than during the Middle Ages, but in crusader times, it was a lagoon with access from the sea. Later in the campaign, the crusaders would dredge an abandoned canal called al-Azraq to the Nile to bypass Damietta to land troops south of the city. The entrance of the canal is unrecorded, but might have been Lake Manzaleh. Once reaching the east bank of the Nile, the crusaders could encircle the city and starve out the defenders, which appeared to them to be the only method to capture the city.

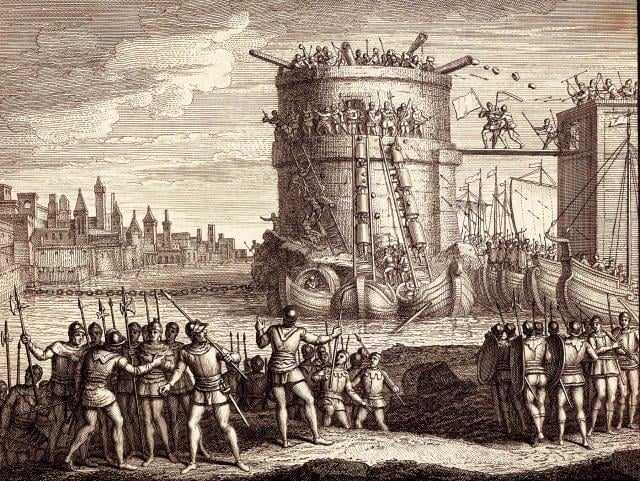

Yet, the Saracens had an even more formidable obstacle that the crusaders needed to conquer before they could cross the river and attack the city in force: the sea or chain tower of Damietta, reportedly 70 “tiers” tall. It is unclear whether a tier is equivalent to a floor in a modern building, but in any event, it awed the crusaders. The tower sat on a small island in the middle of the Nile and was designed to prevent hostile ships from reaching the city or sailing up the Nile toward Cairo. It did this by anchoring two heavy chains across the river, one to the city and one to the west bank, a standard defense in the days of wooden ships. Hence its description as “chain tower.”

The tiered construction of the tower—presumably circular walls decreasing slightly in diameter as the height of the structure increased, looking like an expandable/collapsible telescope at full length—allowed the defending Saracen force of 300 to rapidly position themselves to repel attack from any direction or elevation. Attempting to scale lower levels using typical scaling ladders would have been difficult from the decks of ships because of the motion of the water, something that the crusaders learned from experience. Apparently, the size of the island did not permit assembling a large assault contingent on land, although there was a pontoon bridge connecting it to Damietta that the Saracens could use for resupplying forces. Nor could the tower be “mined” (undermined) by digging tunnels underneath, a standard—albeit difficult—medieval tactic.

Initially, the crusaders attempted to bypass the tower altogether by attacking the sea walls of the city with catapults—called petraries—and ballistae mounted on their ships. Under the leadership of Duke Adolf of Berg (who later died in the siege), the Frisians and other Germans modified one ship into what Arab historians call a “maremme.” In addition to the castle structures fore and aft, the maremme had protection for its ballista and a “small fortress” attached to its mast.

Yet siege machines small enough to mount on cogs would do little damage to the walls. They could, however, kill defenders and have a demoralizing effect on the populace. Throw-weights of the siege engines were constrained by the sizes of the ships, and so they could not match the larger equivalents on land that were designed to wear down and tumble heavy walls.

Worse, however, was that the ships—including the maremme—operating near the city were vulnerable on both sides to fire from the city and the tower. Fire meant both missile weapons and the “secret weapon” of the medieval age, Greek fire, which—being lighter than water—could not be extinguished with H2O. Even today, the exact formula for Greek fire remains unknown, but the closest approximation is napalm.

To combat Greek fire, the crusaders maintained the equivalent of damage-control parties—assigned sailors were armed with buckets of sand, gravel, or acid to quench the flames. As Oliver describes concerning the maremme, “It was seized upon by fire; and although the Christians feared that it would be entirely destroyed, its defenders bravely extinguished the flames.” Nevertheless, operating between tower and city was untenable. The tower had to be taken.

Frustration Leads to Innovation . . . and Victory

Crusaders commenced the assault on the tower using the maremme and two cogs equipped with scaling ladders. The plan was to bring the cogs alongside the lower walls of the tower with troops rushing up the ladders. The maremme would keep up a bombardment.

Not only were the defenders ready for the assault, but the currents prevented the cogs from remaining in place, although a supporting cog (without ladder) of the Templars managed to moor alongside the island until enduring “no slight damage.” The whole operation ended in disaster. In Oliver’s words:

the ladder of the Hospitallers was shattered and crashed into the mast, hurling its warriors headlong; the ladder of the Duke (Adolf of Berg), being broken in like manner at almost the same time, sent up to heaven soldiers who were vigorous and well-armed, wounded in body to the advantage of their souls, crowned with a glorious martyrdom.

Word of this crusader defeat was transmitted to the city and all the way to Cairo by the rejoicing Saracens.

Another attempt at bombardment by the maremme anchored between the tower and the city, also ended in failure; the damage-control parties could not keep up with the volume of the Greek fire from the defenders, although the vessel itself was saved after withdrawing.

The situation seemed gloomy indeed for the crusaders. Oliver gives a definitive after-action report:

we realized that the tower could neither be captured by the blows of petraries or of trebuchets [larger siege catapults on the west bank of the river], for this was attempted for many days; nor by bringing the fort [maremme] closer because of the depth of the river; nor by starvation, because of the surroundings of the city; nor by undermining, because of the roughness of the water flowing about.

After four months of attempts against the tower, the solution was the construction of a one-of-a-kind vessel built by the Frisians and Germans. Two cogs were lashed together with beams and ropes. Enough masts and sailyards were erected to support a larger fortress than the maremme. The structure, which may have been round, was roofed and covered with skins for protection against the Greek fire. But this fortress also was equipped with the equivalent of an amphibious bow ramp (albeit perched high) that extended 45 feet beyond the vessel’s prow. Oliver refers to it as a “movable bridge.” The construction was laborious and cost an additional 2,000 marks for supplies.

Once the construction was completed, the crusade leaders were quite impressed, stating that “such a work of wood had never before been wrought upon the sea.” In his history, Oliver claims no credit, modestly stating that the design and construction were carried out “with the Lord showing us how and providing an architect.” However, all the other eyewitnesses who chronicled the campaign insist that the architect was Oliver himself.

The crusaders swiftly isolated the island and conducted their pre-assault bombardment. Oliver explains, “We realized that we must hasten, because by frequent blows of the (siege) machines, the bridge which conveyed the enemies of the faith from the city to the tower in great part had been destroyed.” On 24 August 1218, “with the greatest difficulty and danger,” the crusaders towed and pushed the new vessel “from the place it was made to the tower,” despite a torrent resulting from the Nile overflowing its banks.

Once “the ropes and anchors were finally firm, although the force of the flooding waters strove to drive it back,” and the archers in the fortress attempted to disperse the tower’s defenders, the “bow ramp” was lowered onto an upper level. Initially the assault was thwarted when the Saracens smeared the end of the ramp with oil and, using their spears as firebrands set it afire, “and when the Christians who were on it ran to put out the fire [amidst the armed troops] . . . their weight [was] so much that the movable bridge . . . was made to bend.” Subsequently, the standard bearer of Duke Adolf’s contingent lost his balance and fell off, which seemed a bad omen. But a Frisian charged the Saracen standard bearer and seized the sultan’s banner, which greatly encouraged the crusaders crossing the ramp.

Soon, the crusaders had driven the defenders into lower tiers. But from the lower tiers the defenders set a fire that forced the crusaders back across the ramp because of the heat.

Oliver had prepared for such a contingency. In interpreting his account, most historians assert the ramp was designed so it could be lowered in its entirety by a system of pulleys. However, a careful reading of Oliver’s narrative seems to indicate the crusaders had built a second ramp below the fortress to access the lower tiers. This ramp was swung down, and the crusaders swarmed into the lower levels, breaking interior walls with mallets and trapping the defenders between them and the fire. Some of the defenders jumped from the tower into the river and attempted to swim, but most were captured or drowned.

After a battle that raged for 25 hours within the tower, the Saracens surrendered on condition their lives be spared. Out of the 300 or more defenders, about 100 remained. The crusaders then broke the chains that barred the Nile and, using the cogs, built their own pontoon bridge so that their forces could cross to the east bank and begin the siege of the city itself.

The loss of the tower has been described as a “staggering blow,” and according to the Arab chroniclers, gloom now settled throughout the Muslim world. They record that as soon as the loss was reported to the ruling sultan, Abu-Bakr al-Adil—who was campaigning against crusaders in Syria while his eldest son, al-Kamil, took care of affairs in Egypt—he fell dead.

The Continuing Campaign and the Offer

The siege and remaining campaign become a slow back-and-forth struggle between al-Kamil’s forces and the crusaders. Al-Kamil had camped his forces some distance from the city but did not reinforce it. Much of the crusading army stayed on the west bank because the Nile was flooding. Impatiently Oliver implored the leaders to attack at once and expressed disgust at their sloth. Disease became rife in the camps. Some of the Frisians sailed for home, considering the capture of the tower as enough of a crusade. New reinforcements sailed in, but other warriors sailed away in a continuing, almost chaotic turnover. The crusaders eventually encircled the city and set up siege engines, which were destroyed by a sortie of the defenders and then rebuilt. Attempts were made to hastily construct another large siege vessel by fastening six cogs together (apparently without Oliver’s help), but it was captured and burned by the Saracen defenders. While besieging the city the crusaders also had to defend against al-Kamil’s army to the south.

Al-Kamil took advantage of crusader lethargy by constructing a dike and scuttling ships a mile up the river from Damietta to prevent further progress up the Nile. The crusaders sent cogs and a smaller, faster vessel they called a “barbote” (of unknown characteristics) up the river to break through but were stymied by losses. The new sultan’s initial strategy was to block any movement toward his capital of Cairo and leave Damietta to defend itself. At the same time, he—a Sunni—had to keep a lid on a potential Shiite uprising in Cairo.

Amid this activity, the greatest disaster of the campaign befell the crusaders: the Pope-assigned political leader, Papal Legate Pelagius, arrived to take command. In the words of a modern historian, Pelagius was “imperious, proud, headstrong, and dogmatic, over conscious . . . of his lofty position . . . and literal in his interpretation of his mandate.” For a while, his presence seemed to breathe new life into the campaign and the crusaders conducted several successful operations against al-Kamil’s army, including capturing its camp. But the defenders of Damietta held on while Pelagius alienated the war leaders and crusader contingents clashed with each other, primarily the remaining Germans versus Italians who had arrived with Pelagius. The siege dragged on.

Pelagius was not the only one to arrive following the capture of the tower. An otherworldly itinerant monk arrived intent on persuading al-Kamil to convert to Christianity—which would end the bloodshed. He was Francis of Assisi, later canonized as Saint Francis. In what the crusaders must have considered a suicidal mission, Francis and another monk, possibly an interpreter, walked unarmed and unannounced to the Saracen lines and requested to meet with the sultan. Whether because of his gentle, ethereal nature, harmless appearance, or simply the bizarreness of the situation, he was granted an audience. The sultan listened politely to Francis’ preaching and—despite the desires of his followers to kill the strange young man who argued against the Koran—allowed him to return to the crusaders unmolested. Obviously, al-Kamil was not converted.

By spring 1219, the continual battling between al-Kamil’s force and the crusader army made the sultan realize he could not resupply the Damietta defenders before they starved to death. So he offered the deal that John of Brienne and his followers dreamed of: For departing from Egypt, the Saracens would return Jerusalem and the surrounding territory to the crusaders with the exception of two castles—for which he would pay them rent. He also would pay to restore the walls of Jerusalem that had been torn down along with three crusader castles that had been partially destroyed. There would be a truce for 30 years and a portion of the (supposed) True Cross captured by the Muslims would be returned.

Most of the crusader army—particularly those who had assaulted the tower—was ecstatic. Pelagius said no. He would never sign a treaty with infidels, and the army would march on Cairo.

More of the original crusaders sailed away. Some accepted money from the sultan to sabotage Pelagius’ plans. Damietta was finally captured by the remaining crusaders on 4 November 1219 after a 14-month siege. According to Arab chroniclers, the “entire Muslim world lamented” and was in a panic. Al-Kamil renewed his offer, which Pelagius again rebuffed.

New crusader reinforcements arrived to strengthen the force—including an unlikely number of 600 cogs to force the way upriver—and the war continued for two more years. But the final march on Cairo—planned ineptly by Pelagius—resulted in such a disastrous defeat (at Mansurah, one-third of the way to Cairo) that the remnants of the crusader army had to retreat to the city and became the besieged. On 30 August 1221, the crusaders agreed to surrender Damietta back to al-Kamil and sail away. Ironically, in an exchange of temporary hostages to ensure both sides honored the deal, the crusaders sent the dutiful John of Brienne. Thus ended the Fifth Crusade as a “colossal and irredeemable failure.”

The Overlooked Maritime Role

The maritime operations of the crusades have been greatly neglected by most historians—treated as a sideshow even though they ensured the survival of the crusader states and included such critical battles as the capture of the tower and siege of Damietta. These extensive maritime operations ranged from sea battles to force projection. There even were “Viking” crusaders (Christianized, of course) who sailed their long ships to the Levant. Perhaps someday there will be some exciting and extensive literature written on the history of the crusader and Saracen “navies of God.”

Sources

Oliver of Paderborn, “The Siege of Damietta,” in Edward Peters, ed., Christian Society and the Crusades, 1198–1229 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971), 48–139.

Francesco Gabrielli, Arab Historians of the Crusades (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1957; republished by Barnes & Noble, 1993).

Thomas F. Madden, The New Concise History of the Crusades (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006; republished by Barnes & Noble, 2007).

Edgar H. McNeal and Robert Lee Wolfe, “The Fifth Crusade,” in Kenneth M. Setton, gen. ed., A History of the Crusades, volume II: The Later Crusades, 1189–1311 (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969).

James M. Powell, Anatomy of a Crusade, 1213–1221 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986).

John P. Donovan, Pelagius and the Fifth Crusade (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1950).