In October 2021, the popular online massive multiplayer game World of Warships released a peculiar ship into the game’s U.S. fleet. Named the USS Kearsarge, the ship seems to be a work of pure imagination—but interestingly, this seemingly insane piece of naval engineering could have very well seen service during World War II.

On page 368 of the recently re-released Naval Institute Press book Russian and Soviet Battleships by Stephen McLaughlin, the ship in question is referred to as Project 1058—ship B (1058.1). To its designer, William Francis Gibbs of Gibbs & Cox, this ship was “Ship X.” Gibbs’s design envisioned an enormous ship some 1,000 feet long with four triple gun turrets mounting 16-inch/45-caliber rifles of the type used in the North Carolina– and South Dakota–class battleships, as well as a 402-foot long flight deck mounted amidships in place of a traditional superstructure. An island conning tower and funnel were offset to starboard like an aircraft carrier.

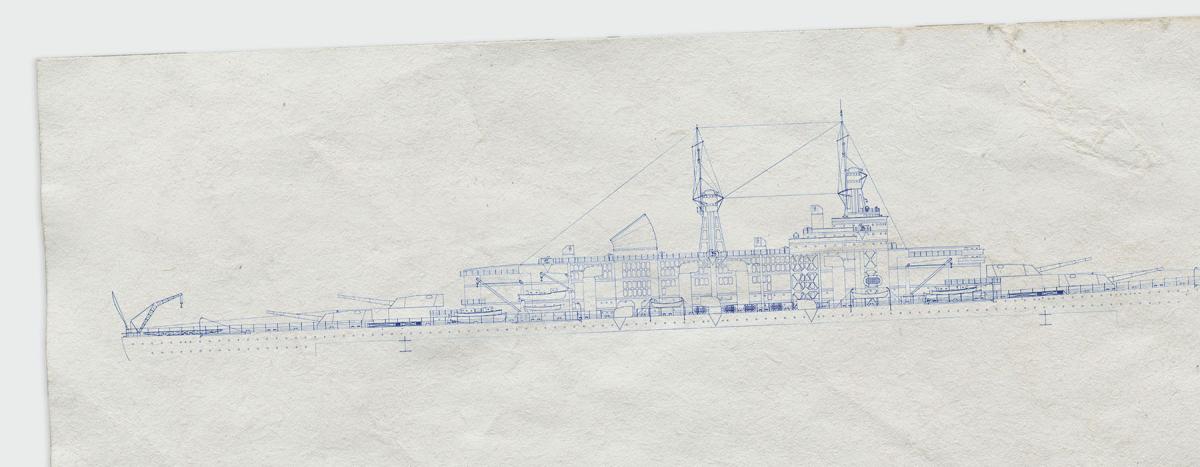

As shown here in this rare 1930s ship’s blueprint, a recent donation to the U.S. Naval Institute Archives, the vessel was, from the keel up, a hybrid carrier battleship—unlike the converted Ise-class battleships of the Imperial Japanese Navy. What had inspired such a design? Was it a fantasy? The twisted imaginings of an eccentric ship designer run wild? What is the real story of “Ship X” and what could have been?

When Joseph Stalin declared in the 1930s that the Soviet Union would develop a modern navy with state-of-the-art battleships at its core, there were a few problems, to say the least. Russia had not built a battleship since the Tsarist period, and its industry was not up to the task of manufacturing a modern battleship, let alone a whole fleet of them. At the time, Great Britain, Japan, Germany, Italy, and the United States were the only countries who possessed the means to build modern battleships. For various political reasons, Japan, Germany, and Great Britain were excluded; Italy and the United States would serve as the primary resources for Soviet naval designs during the interwar period.

Beginning in 1936, the Carp Import and Export company—led by Sam Carp, a naturalized U.S. citizen and brother-in-law of Vyacheslav Molotov (Stalin’s confidante and the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs)—was tasked to procure the necessary components and materials from the United States for the Soviet fleet program. President Franklin D. Roosevelt seemed to signal his support, but after a year and a half of political and bureaucratic roadblocks, especially from the U.S. Navy, Carp had little to show for his work. American leadership could not decide whether helping the Soviet Union build warships of any kind, much less battleships, would benefit the United States in the long run. Many thought not, including Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William D. Leahy. Frustrated, Carp approached Gibbs & Cox, the largest private naval architecture firm in the world, in August 1937.

Carp asked Gibbs to design a ship of unmatched scale and capability that could rule the seas for many years to come. Gibbs set to work designing what he thought would be the ultimate battleship: one with heavy armor, numerous main battery guns—and the aviation facilities of an aircraft carrier.

Therefore, the ship also would need to possess sufficient length to beam and a concomitant shaft horsepower to achieve a top speed greater than 30 knots—no small feat. Numerous drafts for “Ship X” were created, but the version finally settled on would displace more than 62,000 tons (74,000 tons fully loaded). By comparison, the design displacement of the North Carolina-class battleships was 35,000 tons. To accommodate such a leviathan, U.S. dockyards would need to be expanded at Soviet expense. Additionally, the U.S. Navy required Gibbs and Cox to provide it with their designs.

The initial deal called for two of these monster “battle carriers” to be built, one by Bethlehem Steel and the second in Vladivostok, assembled from pieces manufactured in the United States. The U.S. government wished to build two complete ships and provide the materials for a third, but the negotiation only served to delay the project. In the end, bureaucrats opposed to working with the Soviet government obtained Roosevelt’s decision to halt any further work, the stated reason being that building these ships would be in violation of the tonnage restrictions of the Washington Naval Treaty and could be seen by Japan and Germany as a threat. (See “A Template for Peace,” pp. 34–39.) Plans purchased from the United States and Italy would inspire Soviet naval architects to produce a design of their own, which became the Sovetskii Soiuz class, with four hulls ordered in 1938. However, with the outbreak of war in 1939 and the German invasion in 1941, the ships were never completed.

When World of Warships introduced “Ship X” into the game as the Kearsarge, the design team worked from the hypothetical premise that the ship would have been completed by the United States. With the flight deck removed, the ship closely resembles the Montana class of battleships canceled during World War II. Had the first “Ship X” been laid down in 1938, she could have been nearing completion by 1941 or 1942. If so, no doubt she would have ended up serving in the U.S. Navy, as the Soviet Navy was incapable of taking delivery and supporting such a ship by this time. That being the case, how might the U.S. Navy have used the “battle carrier”?

With her high speed, heavy guns, and aircraft, the Kearsarge might have protected convoys headed to Great Britain or the Soviet Union. In the Pacific, she could have provided a stop-gap measure during the early phase of the war, when carriers and fast battleships were in short supply.

Or was the design too inherently flawed to be useful? The flight deck would be too small to operate late-war aircraft, and the deck also impeded main battery firing angles. Ultimately, we can only speculate what this monster of the seas would have done in World War II.

—Jack Russell