An Allied armada hoisted anchor on 6 June 1944 and departed its base to force a landing on a hostile shore. The result would prove decisive to the outcome of the World War II and would free an enslaved population from years of brutal oppression.

That day the world’s attention was focused on the north coast of France, where Allied troops were pushing inland in the largest-ever amphibious assault. While Operation Overlord would become the one and only D-Day in the public’s mind, in truth there were many other D-Days, many other H-Hours on many beaches throughout the world. From 1942 through 1945 the U.S. Navy conducted more than 50 amphibious landings. One was Operation Forager, launched that very same day to conquer the island of Saipan 1,500 miles south of Tokyo in the Marianas.

The Japanese were defending the outer barrier of their empire. Drawing a straight line almost due north, only Iwo Jima and the Bonin Islands stood between the Marianas and Tokyo. For most of the Americans, it was one step closer to the ultimate battle expected on Japanese soil some time in 1945 or 1946.

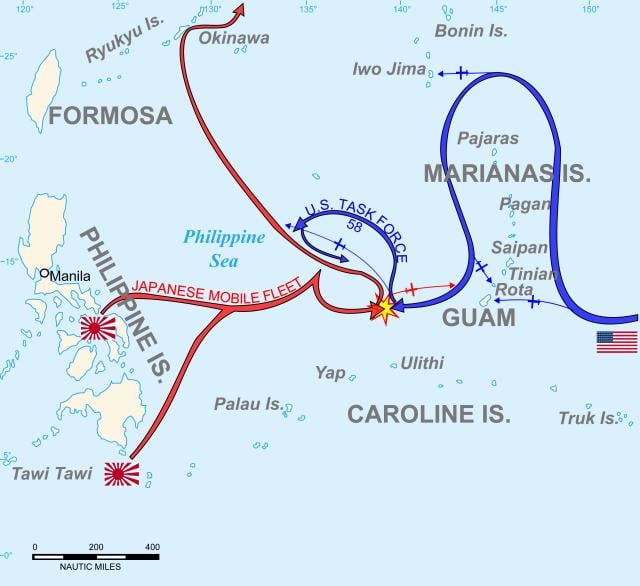

Both sides knew the stakes, and both committed their first teams. There had not been a fleet engagement since the Guadalcanal campaign in October 1942—the sanguinary carrier battle off the Santa Cruz Islands with loss of USS Hornet (CV-8). Now, Vice Admiral Willis Lee’s Task Group 58.7 boasted 111 warships, including 15 fast attack carriers and seven powerful capital ships, none more than four years old. Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa’s force contained all 60 ships, including nine of Japan’s deployable aircraft carriers and five battlewagons—including the Yamato and the Musashi, the largest ships afloat.

Without the flattops, Forager could have proved to be a memorable gunfight. But the only rounds that would be fired by the battleships were aimed at aircraft. The Battle of the Philippine Sea would go into history as “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.”

“An Old-Time Turkey Shoot”

Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher’s Task Force 58 opened Operation Forager by launching air strikes against Saipan and its neighboring islands on 11 June 1944. Assault troops splashed ashore beginning on the 15th. As the island was secured, Martin PBM-5 Mariners from Patrol Squadron (VP) 16 began operating from alongside the tender USS Ballard (AVD-10) anchored offshore. Early on the 19th, one of the Mariners picked up a large radar contact—an estimated 40 ships 470 miles west of Guam. However, atmospherics interfered with the transmission, and timely intelligence was lost.1 The battle was not.

The epic carrier duel that ensued lasted just two days. On 19 June Mitscher’s Hellcat pilots and fighter directors conducted a near-perfect defense, repelling four Japanese raids totaling some 326 aircraft. Simultaneously, Japanese land-based planes also were hunted to destruction. It was the Hellcat’s greatest moment—in the space of several crowded hours U.S. carrier pilots claimed 380 kills (368 by F6Fs), dwarfing any other one-day score in American history.

Though Mitscher’s air groups were defensive on the 19th, American submarines found the Japanese Mobile Fleet. The USS Albacore (SS-218) sank Ozawa’s flagship from beneath him, sending the brand-new carrier Taihō to the bottom. That same morning the Cavalla (SS-244) torpedoed Shōkaku, which had taken part in the raid on Pearl Harbor and was a veteran of every carrier battle except Midway. She lingered on the surface for a few hours before internal fires set off secondary explosions that blew her hull apart.

The day ended on a high note. During a debrief aboard Mitscher’s flagship the USS Lexington (CV-16), a fighter squadron (VF) 16 pilot, Lieutenant (junior grade) Ziegel “Ziggy” Neff, harkened back to his Missouri roots. After four victories he reckoned the battle was “just like an old-time turkey shoot.”2 The “brown shoe” aviators were jubilant—they knew they had inflicted severe losses on Japanese naval aviation and expected to finish the job.

The following afternoon, search teams from the Enterprise (CV-6) found Ozawa, withdrawing northwesterly. Closing the distance, Task Force 58 launched the “mission beyond darkness,” sending 240 aircraft winging into the setting sun, seeking one last, cherished chance at Japan’s remaining flattops. It was a long shot in the literal sense—the distance to the target was a fuel-stretching 300 miles. The Enterprise’s Bombing Ten skipper, Lieutenant Commander James “Jig Dog” Ramage, spoke for many command officers when he told his pilots, “We are going to be gas misers.”

En route to intercept the Mobile Fleet, some squadrons opted for the first available targets. One air group jumped on Ozawa’s trailing support force, sinking two oilers, while the other formations continued toward “the fighting navy.”3 Amid a sprawling, confused attack on Ozawa’s three task groups, TBM Avengers from the USS Belleau Wood (CVL-24) sent the carrier Hiyō to the bottom, and carrier aviators damaged other ships as well.

Then it was time to turn for home beneath a moonless sky. Task Force 58 lost far more aircraft to operational causes than to combat. Throughout the day Mitscher had lost 37 aircraft, including 21 Hellcats. The CVEs and VP-16 wrote off one plane each. Scores of planes splashed out of fuel or crashed in the frenzied effort to get aboard any deck that could take them. Curtiss SB2C Helldivers were especially hard hit. Of the 51 launched, 40 were lost. Ironically, the aging Douglas SBD Dauntless, with which two of the fast carrier squadrons were equipped, handily outperformed its replacement. But the Bureau of Aeronautics had already made the decision: Helldivers were to remain in production while the Dauntless production line would shut down the following month.

That evening, Task Force 58 lost 120 aircraft. Mitscher has received wide praise for his decision to “turn on the lights,” risking enemy detection, but in truth he lost control of the situation. Nearly every ship in the task force lit up, confusing many airborne pilots. Some made landing approaches on cruisers and even destroyers, using gasoline they did not have to spare.

After Saipan, the effects were felt immediately in Tokyo. Prime Minister Hideki Tojo’s cabinet fell, and within months Marianas-based B-29 Superfortresses began burning out the heart of Japan’s urban-industrial areas.

Forager in Perspective

Three-quarters of a century downstream from Forager, it’s possible to place the Battle of the Philippine Sea in perspective. It remains the third-largest naval battle of the steel-ship era, with 207 carriers, surface combatants, and submarines engaged; the three-day surface and air actions at Leyte Gulf was the largest ever fought, involving some 244 warships and subs plus 39 PT boats.4

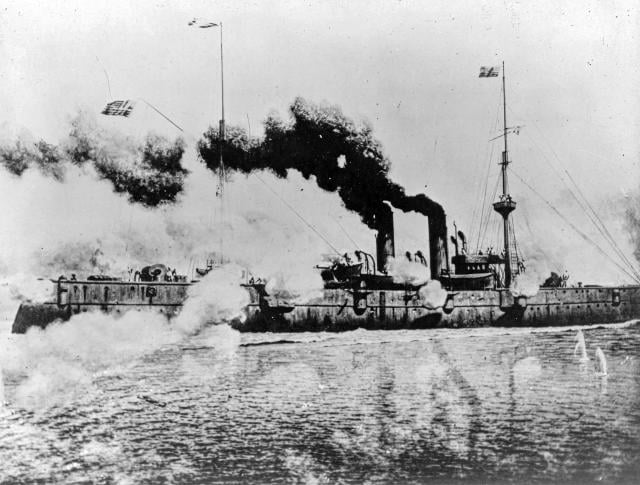

Excepting the Battle of Jutland, the Marianas battle dwarfed anything previous since the age of sail. The first great clash of ironclads occurred between Russia and Japan in 1905, with 81 capital ships and destroyers plus 16 Japanese torpedo boats. A century before Tsushima Horatio Nelson’s epic victory at Trafalgar involved only 60 British, French, and Spanish ships.

The largest American naval battles prior to World War II occurred during the 1898 war with Spain. At Manila and Santiago Bays about 30 ships were directly engaged. But the combined tonnage at Manila Bay barely matched the standard displacement of a single Essex-class carrier. By comparison, the two biggest dreadnaught battles of World War I were Jutland in 1916 with 251 combatants and Dogger Bank in 1915, with approximately 100.

As historic naval battles of their respective eras, Jutland and Philippine Sea provide illuminating contrasts. Strategically, Jutland and Forager had nothing in common. Of interest to tailhookers, Jutland was the first fleet engagement to have involved aircraft; HMS Engadine, a 1,700-ton seaplane carrier, accompanied the British battle cruisers. On the afternoon of 31 May, Engadine craned a Short 184 over the side in response to reports of smoke on the eastern horizon. The floatplane found German screening forces and radioed a contact report.5 Jutland remained the classic naval gun battle, involving 153 British ships (1,263,000 tons) and 98 German (512,000 tons). Yet the badly outnumbered High Seas Fleet sank 14 Royal navy ships (118,000 tons) while losing 11 (65,000 tons). Though Germany’s High Seas Fleet won a tactical victory in the North Sea, the overall situation remained unchanged. Germany felt the increasing effect of the naval blockade for the rest of the war.

Nothing that occurred in the European theater in World War II was remotely close in comparison to the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The biggest naval battles fought against the western Axis occurred in the Mediterranean in 1940–1942, and frequently they were inconclusive. For instance, in the Battle of Cape Spartivento in November 1940 more than 50 British and Italian ships fought without loss to either side. Though heavy merchant losses occurred in the June 1942 Malta convoy battles that pitted 65 British combatants against 58 of the Axis, many Royal navy warships were not directly engaged.

The short interval between the World Wars was notable for the decline of the battleship and rise of the carrier. In those two decades, new technologies were invented—most notably radar—while others were perfected, including radio, ordnance, and the airplane itself. The respective fleets had vastly extended engagement ranges from about 17,000 yards in 1916 to 300 miles in 1944. The world’s navies had commissioned about 45 battleships after the Great War. In 1939 the global population of battlewagons was pegged at 55; carriers numbered 18. Yet six years later on V-J Day almost the only deployable battleships flew the Stars and Stripes or the White Ensign.

Since 1922 the world’s navies have produced 269 conventional carriers, 189 of which have been built in America, including 38 for the Royal Navy. Other tailhook contenders are Britain with 49; Japan with 24; France with 4 and Russia with 1. Yet, barely three dozen carriers ever fought their own kind, and 15 (3 U.S. Navy) were victims of “CV fratricide.”6

The Pacific War was unique—no other conflict has revolved around aircraft carriers. The 1942 naval battles of Coral Sea, Midway, and Guadalcanal were decided wholly or in part by shipboard aircraft. But the Battle of the Philippine Sea remains the greatest carrier duel of all time. In terms of flattops directly engaged, it exceeded all that preceded it. None of the four carrier clashes of 1942 committed more than seven flattops; “Phil Sea” even outnumbered carriers in the subsequent slug fest at Leyte Gulf in October.

The scale of Forager remains stunning. Excluding Admiral Raymond A. Spruance’s Fifth Fleet amphibious forces and support units, Task Force 58’s 111 ships were crewed by nearly 100,000 sailors and fliers, while the Japanese Mobile Fleet’s 60 ships deployed with almost 30,000 more. By World War II standards, those numbers equaled seven U.S. Army divisions and two of their Japanese counterparts.

The carrier tonnage off Saipan was awesome: 270,000 U.S. to 176,000 Japanese, and that does not include U.S. escort carriers supporting the landings. By comparison, the combined U.S. Navy and Imperial Japanese Navy carrier tonnage at Midway was less than what Ozawa took to the Marianas.

In June 1944, the U.S. Navy had 644 warships and submarines in commission; the Imperial Navy, 165. The four-to-one disparity was misleading because America sustained a two-ocean navy. However, the true striking power—aircraft carriers—was heavily concentrated in the Pacific, while CVEs pursued the Atlantic U-boat campaign.

Ozawa’s nine carriers embarked 437 aircraft, many being older model A6M2 Zeros doubling as bombers. Additionally, Japanese land-based air groups were authorized 500 planes in the Marianas, at least half of which were on hand. Task Force 58’s 15 carriers entered the battle with 873 aircraft—463 fighters, 217 dive bombers and 193 torpedo planes. Mitscher’s battleships and cruisers embarked an additional 57 floatplanes, largely OS2U Kingfishers, for a total of 905.7

In June 1944 the U.S. Navy had 47,000 aviators for 34,000 aircraft. On the first of that month, 86 carriers (including 56 escort carriers) were in commission—a figure that would be eclipsed 12 months later. At year’s end, the U.S. Navy possessed 6,084 ships of all types, excluding landing craft.8

Today the Navy owns about 2,600 manned aircraft, including helicopters, excluding the Marine Corps and Coast Guard.9 As of 2019 the Navy reported 289 deployable ships out of a total of 480. Meanwhile, the Navy has 232 flag officers versus 342 admirals and commodores at the height of World War II, with a small fraction of the force structure. “Admiral inflation” with nearly as many flags as ships has been offered as a possible Gilbert and Sullivan opera. In some years there have been more flags than hulls.10

If the equipment was vastly different 75 years ago, so were the people. At the end of 1944 the Navy (excluding the Marines and Coast Guard) counted 3.2 million personnel. Today’s numbers are approximately 330,000 active duty and 100,500 ready reserve. In World War II the median age of carrier aviators was 24 while aircrew averaged 22. Most had received their wings in the years after 1941, yet off Saipan there were 20-year-old pilots and 19-year-old gunners. Today, few aviators under age 25 are in deployed squadrons.

But numbers were only part of the equation. Invisible beneath quantities of people and tonnage of ships was America’s enormous qualitative edge, both human and material. Japan’s early advantage in highly skilled aircrew had steadily eroded through two and a half years of attrition. U.S. Navy airmen were both more experienced and better trained. It was those men who won that the penultimate fleet engagement in world history, fought in the bright sunlight of a cerulean Pacific sky.

We will never see a battle of its like again.

1. Bruce Petty, “VP-16 and Operation Forager,” Warfare History Network, 3 January 2019.

2. Barrett Tillman, On Wave and Wing: The 100-Year Quest to perfect the Aircraft Carrier (Washington, DC: Regnery History, 2016), 196.

3. James D. Ramage, interviewed by Robert L. Lawson and Barrett Tillman, The Reminiscences of Rear Admiral James D. Ramage, U.S. Navy (Retired) (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 1999).

4. Samuel Eliot Morison, U.S. Navy Operations in World War II: Leyte, Vol. XII (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1956.)

5. On Wave and Wing, 7.

6. On Wave and Wing, 269.

7. Barrett Tillman, Clash of the Carriers: The True Story of the Marianas Turkey Shoot (New York: NAL Caliber, 2005), 305–306.

8. Naval History and Heritage Command, “U.S. Navy Active Ship Force Levels, 1938-1944,” 17 November 2018.

9. United States Navy, “Status of the Navy,” as of 14 June 2019.

10. Statistica Ltd., “Total military personnel of the U.S. Navy from the FY 2018 to FY 2020, by rank,” March 2019.