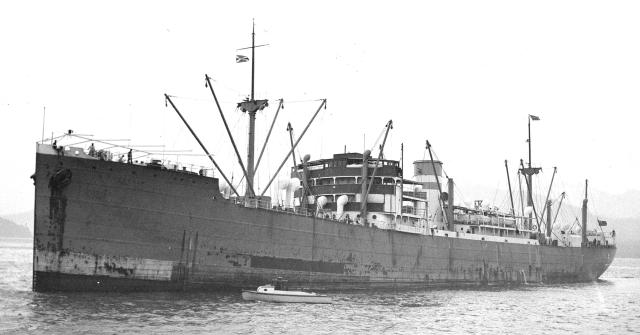

Just before midnight on 23 October 1933, the British-flag motorship Silverpalm finished loading her cargo in San Francisco and left San Francisco Bay, bound south to the Panama Canal. Earlier that day, four U.S. Navy cruisers—the USS Chicago (CA-29) and her sisters Northampton (CA-26), Chester (CA-27), and Louisville (CA-28)—had left San Pedro for a run north to reach San Francisco for a Navy Day celebration. As the flagship of Vice Admiral Harris Laning, commander of the cruisers of the fleet’s Scouting Force, the Chicago led the column of cruisers.

The Collision

The captain of the Silverpalm was Bernard T. Cox, an experienced mariner and Royal Navy veteran. After leaving San Francisco Bay, he increased the Silverpalm’s speed to 13.5 knots. Approaching him from the south were the four U.S. Navy cruisers, steaming in a line-ahead formation at 12 knots. In command of the Chicago was Captain Herbert E. Kays; his navigator was Lieutenant Commander Lloyd R. Gray. Both Cox and Kays took extra precautions with their ships—slowing down and sounding their ships’ foghorns—when they approached fog banks that periodically reduced visibility.

At 0745 on 24 October, Vice Admiral Laning authorized Captain Kays to increase the Chicago’s speed to 18 knots to comply with a Bureau of Engineering directive that she do so in order to anneal a new coating of her boilers. On the bridge of the Chicago, Captain Kays and Lieutenant Commander Gray were watching for any ships that might emerge from fog banks that paralleled the Chicago’s course.

Hidden in the fog ahead and to starboard of the Chicago was another merchant ship, the SS Albion Star. Her captain, Selwyn Capon, had heard fog signals earlier from two ships located on the Chicago’s starboard quarter. At about 0745, the signals began coming from the port quarter, which meant to Capon that the two ships he already had heard were overtaking his own. He made sure that the Albion Star sounded her whistle.

At about 0800, Vice Admiral Laning heard the Chicago sound two blasts of her whistle, signaling that she was slowing. He quickly climbed to the flag bridge. The starboard lookout told him there was a ship to starboard. Laning and the lookout looked and listened—and then heard the Albion Star’s whistle. The Chicago answered with her own whistle, and then Laning saw the Albion Star ahead of the Chicago to starboard. Captain Kays also had heard the Albion Star, and as the merchant ship slowly emerged from the fog bank, he saw that the Chicago was on a converging course. He intended to pass her to her left.

Suddenly, lookouts and the Chicago’s bridge watch saw the Silverpalm coming fast from the fogbank to port. She was headed straight for the cruiser. Captain Kays first thought he could avoid a collision, but then he almost immediately realized that he could not, and he ordered the Chicago’s rudder over full and her engines backed “emergency.” He also ordered the collision alarm sounded. On the Silverpalm, Captain Cox rang for full speed astern, and his engineers quickly cut off fuel to the ship’s two big diesel engines. Tragically, the engines continued to turn over; they could not be reversed until they were nearly at rest. As the Silverpalm bore down on the Chicago, Cox could only order his crew to prepare for a crash.

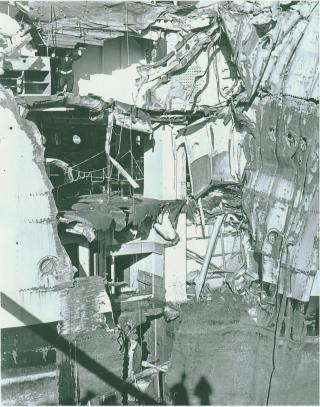

According to the Chicago’s quartermaster, the two ships collided at 0807, the Silverpalm’s stout bow smashing into the Chicago’s port side ahead of her forward turret at an angle of about 40 degrees. Three members of the crew were killed by the impact.1 One escaped with serious injuries.

Immediately after the collision, the two damaged ships separated and sailed independently to San Francisco.

Immediate Aftermath

News of the collision reached the 12th Naval District and triggered two different but related legal proceedings. One was a Naval Board of Inquiry. The other was a libel hearing in the federal district court for the southern division of the northern district of the state of California, in accordance with accepted admiralty law. It also was accepted practice for a representative of the federal district attorney to attend the Navy Board of Inquiry as an observer. Accordingly, District Attorney Henry H. McPike assigned Assistant Federal District Attorney Esther B. Phillips to do so, and she quickly realized that the Albion Star had played an important role in the collision. On 29 October, she requested by radio telegram that the Attorney General in Washington instruct the U.S. attorney in Seattle to submit questions to select members of the Albion Star’s crew before that ship left U.S. territorial waters.

On 1 November, McPike filed a libel claim against the Silverpalm. Under admiralty law, there were two types of liability in ship collision cases. The first was liability in rem—that is, in the ship itself. The ship had the right to sue. The Chicago had the right to sue the Silverpalm and vice versa in the federal district court. At the same time, the law also allowed the owner or owners of a ship to sue or be sued. The government of the United States could sue Silver Line Ltd., the owner of the Silverpalm, and Silver Line Ltd. could sue the U.S. government, and that is what happened.2 However, the U.S government could hold the Silverpalm for bail while the owners of the Silverpalm could not do the same to the Chicago.

(National Archives)

Admiralty law also differed from the common law of negligence in other ways. First, litigants in liability cases had no right to a jury trial. Second, admiralty law did not follow the common law doctrine of contributory negligence, where negligence by one party in a case could add significantly to the damages awarded the other party. The rule governing U.S. courts in admiralty cases was that even minor negligence on the part of one ship involved in a collision meant that the costs of any damages had to be divided equally.3 Third, admiralty law had no concept of “no fault” liability; if there was damage, someone was responsible. Fourth, the U.S. government had the right to petition a district court hearing a collision case involving a government ship for a limitation of its liability.

Board of Inquiry

On 25 October 1933, Vice Admiral Laning directed three senior Navy captains to serve as the principal members of a board of inquiry, and he charged them to thoroughly investigate the cause of the collision and to determine who was responsible. To encourage witnesses to speak frankly, the board closed its hearings to the public. The board also ruled that the key witnesses—particularly Captain Cox and Captain Kays—had the right to be represented by legal counsel, and that all witnesses had the right to refuse to incriminate themselves.

As the inquiry proceeded, it was obvious that both Captain Cox of the Silverpalm and Captain Kays of the Chicago could find themselves formally accused of negligence. When the board completed its work, perhaps its most important finding was that it was “impossible to reconcile the evidence given as to the courses being steered and bearings observed when the two vessels first sighted each other.”4 Nevertheless, the board’s opinion was that the Silverpalm was completely responsible for the collision. Accordingly, the board recommended that Captain Cox be charged with criminal negligence and that the U.S. Department of Justice sue the owners of the Silverpalm for damages to the Chicago and for compensation to the survivors of the three members of her crew who had been killed. On 15 January 1934, Admiral David F. Sellers, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet, approved the board’s findings, opinions, and recommendations, and ruled that the Navy would take no further action. Soon afterward, the Justice Department decided not indict Captain Cox on criminal charges.

Suits and Countersuits

Even before Admiral Sellers made his decision, the lawyers representing the Silverpalm and Chicago had filed suits and countersuits in the federal district court. To simplify the legal issues in the various suits, Federal District Judge Harold Louderback on 16 December 1933 consolidated all the libel and damage suits to three: (a) Silver Line Ltd. (Libelant) vs United States of America, (Respondent), (b) United States of America (Libelant) vs Silverpalm (Respondent), and (c) Silver Line’s petition for “exoneration from and limitation of liability.”

There matters stood until 14 February 1934, when the attorneys representing Silverpalm and the Silver Line surprised Federal District Attorney McPike by saying that their clients were willing to settle the liability and damage cases on the basis of mutual fault. The Navy’s position was that the offer to settle the case on the basis of mutual fault appeared “to be of no advantage to the Government except to save the costs of litigation” and that unless it could be shown in court that the Chicago was also at fault, District Attorney McPike should be told to proceed with the case.5

McPike assigned Assistant Federal District Attorney Phillips to try the libel case. Her opponent was Ira Lillick, a well-known attorney in San Francisco. They began presenting their respective cases on 13 March 1934. Phillips’s strategy was to go over the evidence thoroughly to educate Judge Louderback. She had a very strong case. Her strong point was that the Silverpalm’s engines could not be reversed when her officers first sighted the Chicago, and that the Silverpalm had been pressing ahead without due regard for the hazard posed by such engines. Lillick did not have a strong case going into the trial, and he did his best to find any evidence of negligence on the part of Captain Kays and his crew.

The district court trial transcript—over 1,200 pages of it—shows the opposing lawyers working hard to persuade Judge Louderback to adopt their opposed positions. Lillick focused on the behavior and decisions of Captain Kays of the Chicago. Why had Kays begun to increase the speed of the cruiser when there were fog banks to either side of the Chicago? When multiple witnesses testified that Kays had taken what they thought was every precaution, Lillick left that line of inquiry and focused his attention on the throttlemen in the Chicago’s engine room.

Captain Kays had testified that he had ordered the Chicago’s engineers to accelerate around the Albion Star because he knew that if the Chicago encountered another ship heading toward him his engineers could throw the Chicago’s powerful turbine engines into reverse almost immediately and avoid hitting the approaching ship. Phillips produced several witnesses who testified that the Chicago’s engine room staff was engaged in slowing her—and had slowed her considerably—when the collision occurred. Lillick countered this by pointing to unusual changes in the logs of the Chicago’s throttlemen. He noted that such changes were forbidden by Navy regulations, implying that the changes were made to hide the fact that the Chicago had not reduced her speed on seeing the Silverpalm heading toward her.

Examining and cross-examining witnesses went on for days; the sparring between the two leading advocates did not end until 30 March. Attorneys Phillips and Lillick appeared before Judge Louderback to argue which ship was negligent one last time on 23 April; they also answered the judge’s questions. On 8 May 1934, the two sides in the libel case filed their final briefs with the district court. On 10 June, the court found the Silverpalm to be “solely at fault for the collision.” The Chicago was “exonerated.”6 On 12 July, the District Court ruled that the monetary claims of the U.S government against the Silver Line and the Silverpalm would be weighed by a U.S. Commissioner. By this time, both the Silverpalm and Chicago were at sea. Lillick appealed on 24 July 1934.

The Appeal

Though the Navy appeared to have won its case decisively, Lillick knew that if the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals chose to review the judgment of the District Court, the Appeals Court judges did not have to examine the District Court’s lengthy trial transcript. Instead, the judges of the Ninth Circuit could take the case fresh—de novo, and they did just that in 1936. Attorneys Philips and Lillick now had to recraft their briefs in ways that were different than what they had presented in the District Court’s hearing.

(National Archives)

In March 1934, Lillick was the underdog. There was plenty of evidence that the Silverpalm could not stop or reverse her engines quickly. Therefore, Lillick did not defend the Silverpalm but instead searched for weaknesses in the government’s case. He believed he had found two. First, he maintained that the Chicago was moving too fast to stop or to back up when her captain saw the Silverpalm. Second, he argued that the changes made in the Chicago’s engine room throttle logbooks substantiated his claim. Therefore, the Chicago was at least partly at fault, and the responsibility for negligence was shared. Never mind that the Silverpalm was more at fault than the Chicago. What mattered to the Appeals Court was whether the Chicago was negligent.

This put a great burden on Phillips. She had to focus her brief to the Ninth Circuit Court’s judges on defending the Chicago—on showing that the cruiser was not moving too fast given the conditions of visibility and the cruiser’s ability to reverse her powerful engines. She also had to persuade the judges that the changes to the throttlemen’s logbooks were not evidence of a conspiracy. The Ninth Circuit ruled on 28 October 1937 that though the Silverpalm was at fault, the Chicago was equally at fault. Each side had to pay its own damages—including, for the U.S. government, compensation to the families of the members of the Chicago’s crew who were killed.

Senior Navy officers and the government attorneys found the wording of the Ninth Circuit’s ruling astonishing and insulting. Commander Thomas L. Gatch, a senior assistant to the Navy Judge Advocate General, sent Phillips a blistering draft of a petition for a rehearing before the Ninth Circuit Court. His language was so intemperate that Phillips told him not to share it with anyone else. She feared that if he did, he would be punished for contempt of court.7 She saw only two alternatives to the Ninth Circuit’s intemperate language. One was to apply to the Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari in the hope that the Supreme Court would review and then overrule the Ninth Circuit’s decision. The other alternative was to pursue a legislative remedy in Congress.

Phillips had to leave any legislative effort to the Secretary of the Navy. However, with the cooperation of Commander Gatch and the approval of Attorney General Cummings, she drafted a petition to the Supreme Court requesting that the Court grant a writ of certiorari. On 23 May 1938, the Supreme Court declined to issue a writ. As is the custom in such cases, the Court did not have to explain why it rejected the Justice Department’s petition. The Ninth Circuit’s ruling stood.

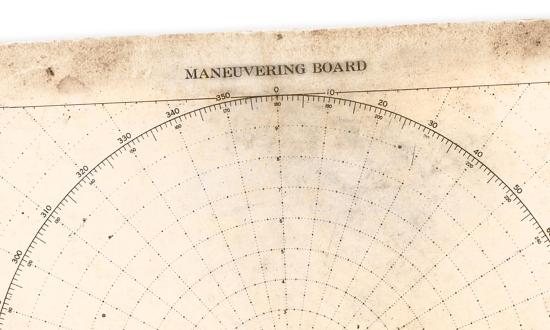

Esther Phillips probably understood why the Supreme Court had turned down the Justice Department’s appeal: because the most critical fact of the case remained uncertain all along—from the Navy’s board of inquiry through the evidence presented to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. That elusive fact was the actual positions of the two ships at the moment each was in sight of the other. In common law, judges assess facts and are guided by legal precedents. The precedents in the matter of Silverpalm v. Chicago were not ones that the Navy favored, but at least they were clear. The facts, however, were in dispute from the beginning, and the court hearings never really resolved that dispute. There is a saying that bad cases make bad law. It seems that this saying applied to Silverpalm v. Chicago. If so, then it suggests why the Supreme Court never took up the case.

1. They were Lieutenant (j.g.) Harold Macfarlane, U.S. Navy, First Lieutenant Frederick Chapelle, U.S. Marine Corps, and Chief Pay Clerk John Troy, U.S. Navy.

2. The Public Vessels Act of 1925 permitted in personam suits against the United States if one of its ships damaged a privately owned ship. See “Navy Admiralty Law Practice,” NAVEDTRA 14350, 12, which draws on Admiralty and Maritime Law, 3rd ed. (2001), by Thomas J. Schoenbaum.

3. See NAVEDTRA 14350, 4.

4. “Record of Proceedings of a Court of Inquiry Convened on Board the U.S.S. Chicago by Order of the Commander Cruisers, Scouting Force, United States Fleet to inquire into a Collision at Sea Between the U.S.S. Chicago and the British Motor Ship Silverpalm,” 26 October to 18 November 1933, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Navy), RG-125, Box 635, Entry 30, Folder 18319, National Archives, Washington, DC)

5. Ltr., from Henry L. Roosevelt, AsstSecNav, to: The Attorney General, L11-15/QM (331110), Mar. 6, 1934, Folder 2, Container 1, RG-118, National Archives Branch, San Bruno (San Francisco), California.

6. “Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law,” Case 21666-L, Harold Louderback, U.S. District Judge, RG-125, Entry UD4, Folder “USS Chicago—Silverpalm Collision Case,” p. 3, San Bruno Branch, National Archives.

7. Ltr., from: Esther B. Phillips, Asst. U.S. Attorney, to: Commander T. L. Gatch, Navy Department, subj: “Chicago-Silverpalm” Collision, Nov. 22, 1937, Records of the JAG (Navy), RG-125, Box 635, Entry 30, Folder 18319, National Archives, Washington, DC.

The detailed story of the collision and the legal cases that followed can be found here.