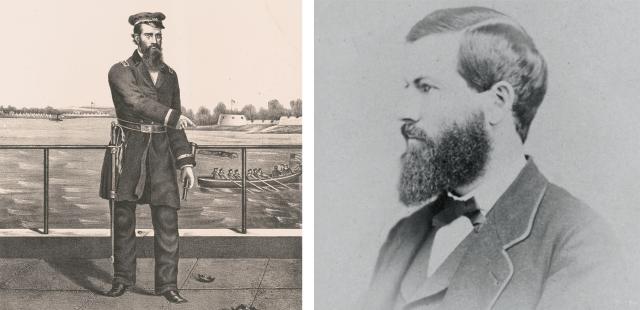

John Lorimer Worden became a Navy midshipman in 1834 and spent the next several decades ashore and at sea, including service during the war with Mexico (1846–48). As the nation moved inexorably toward civil war, Lieutenant Worden recalled that the Secretary of the Navy “wanted me to go at once to Pensacola with dispatches for Captain Henry A. Adams” instructing the latter to reinforce the vulnerable federal Fort Pickens. Many officers were suspected of sympathizing with the South; Worden was chosen for his unquestioned loyalty to the Union. With the peace rapidly crumbling but war not yet commenced, Worden traveled in uniform through several Southern states and delivered his message as ordered. He then began the journey back to Washington, but two days after hostilities commenced with the shelling of Fort Sumter, Worden was taken off the train in Montgomery, Alabama, then the capital of the Confederacy, and incarcerated in the city jail, where he remained a prisoner for the first seven months of the war.

At last released as part of a prisoner exchange, Worden was contacted by Commodore Joseph Smith, chairman of a three-man board earlier appointed by Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles to “investigate the plans and specifications that may be submitted for the construction of iron or steel-clad steamships.” By then, the first such ship was nearing her launching at Greenpoint, New York, and would soon be christened the Monitor. She combined three emerging revolutions in technology—armor cladding, steam propulsion, and a turreted gun. Smith told Worden, “this vessel is an experiment,” and then added, “I believe you are the right man to command her.” Despite his wife Olivia’s urging to the contrary, Worden eagerly accepted.

Plans called for the Monitor to have a crew of 49, including a commander, an executive officer, four engineers, one medical officer, a paymaster, and two masters (essentially navigators). Paymaster William F. Keeler was among the first selected, and he predicted that “if I am not very much mistaken [Captain Worden] will not hesitate to submit our iron sides to as severe a test as the most warlike could desire.” He described the ship’s second-in-command, Lieutenant Samuel Dana Greene, as “a young man . . . [with] black hair & eyes that look through a person & will carry out his orders I have no doubt.” His assessment of both men was soon to be proven accurate.

Greene was indeed young, just shy of his 22nd birthday. He was from Maryland, graduating seventh in his class at the U.S. Naval Academy, and was serving in Asian waters in the sloop-of-war Hartford when the war began. Arriving in Philadelphia after a nine-month voyage home, he soon volunteered for service in the Monitor. At this point in the war, the Union Navy was stretched thin, with naval officers in high demand, which at least partially explained why such a young officer was assigned as executive officer. Commodore Smith was prompted to comment, “A good deal of wonderment and many surmises are afloat.”

The enlisted men were all selected from a bank of volunteers, many with little or no naval service. A few changed their minds and deserted when they arrived and saw the strange vessel that some had described as a “cheesebox on a raft” with her almost nonexistent freeboard and all her crew quarters below the waterline.

Under Way

In February 1862, the Monitor was moved to Brooklyn Navy Yard, where she was commissioned on the 25th. Nine days later, on 6 March, the Monitor took in all lines and headed down the East River with a cold rain falling. John Ambrose Driscoll (who was destined to be the last living member of the original crew) recalled that “nothing but gloom surrounded our departure. The weather itself seemed to mock us, it being one of the most dreary mornings I had ever witnessed.” To improve her speed, the ship was being ignominiously towed by a Navy tug, the Seth Low.

Headed south for Hampton Roads, Driscoll remembered, “With the exceptions of a few men in the turret and in the pilothouse, we were all in absolute darkness excepting the dim rays of light we got from an oil lamp.” Things got worse on the evening of the 7th, when “the gale, which had been threatening all day, commenced to begin with violence.” Waves crashed over the six-foot-high smokestacks and the leather belts driving the ventilation systems began to stretch, causing the blowers to fail. Water cascaded into the ship and the pumps too failed, requiring the crew, many of them suffering from severe sea sickness, to resort to hand pumps.

Miraculously, the ship survived.

By the afternoon of the 8th, she neared Cape Henry, and her exhausted crew was greeted by the sounds of ongoing battle. Making their way into the shallows of Hampton Roads, the crew saw the masts and spars of a Union warship engulfed in flames and soon learned that another ironclad—this one converted from the captured Union ship Merrimac and rechristened as the Confederate ship Virginia—had wreaked havoc among the Union warships, ramming and sinking the sloop-of-war Cumberland and setting the frigate Congress ablaze. The frigate Minnesota had run aground, and only the receding tide had prevented her from being destroyed as the Virginia retreated to deeper water.

As Worden anchored the Monitor near the helpless Minnesota, Lieutenant Greene recalled “an atmosphere of gloom pervaded the fleet, and the pygmy aspect of the newcomer did not inspire confidence among those who had witnessed the day before.” As the night wore on, the men of the “pygmy” prepared for the coming battle, which one witness would describe as comparable to “David and Goliath.”

The Contestants

At 256 feet long, the Merrimac had been one of the largest ships in the Union Navy. Now as the Virginia she was 263 feet long—the additional length a consequence of adding a large battering ram to her bow—compared with the Monitor’s 172-foot length. More than a thousand tons of four-inch-thick armor had been fashioned into a casement with sloping sides that ran the length of the ship, causing some to liken it to the top of a barn. Protruding from the sides of the structure were the muzzles of ten cannon, five arrayed down each side.

The Monitor had only two guns, but they were XI-inch smoothbore Dahlgrens, weighing eight tons each and able to fire a 1,300-pound shot nearly a mile. They were mounted in a movable turret of about 20 feet in diameter, which enabled them to be fired in any direction except dead ahead, where the pilothouse—the only other projection above the main deck—was located.

The Virginia’s engagements with the unarmored Union ships the day before had been one-sided. At one point, the Congress had fired a 32-gun broadside at the ironclad. A soldier on the nearby shore could hear the great blast of the guns but was amazed when the shower of projectiles “rattled on the armored Merrimac [Virginia] without the least injury.” The rampaging ironclad had moved among her adversaries with impunity.

Although both the Virginia and Monitor were ironclads, they were different in several ways, akin to gladiators battling with different arrays of weapons. There had to have been much uncertainty among both crews as the Monitor got underway the next morning and steamed into the arena to meet the oncoming Virginia.

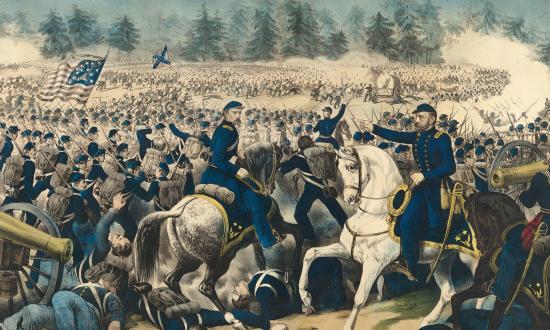

Duel of Iron

The Monitor’s captain was in the pilothouse, peering out through the narrow slit forward, which Worden described as the “lookout hole,” issuing orders to Seaman Peter Williams, who was at the helm. Worden later recalled:

In the gray of the early morning we saw a vessel approaching, which our friends on the Minnesota said was the Merrimac. Our fastenings were cast off, our machinery started, and we moved out to meet her half-way. We had come a long way to fight her and did not intend to lose our opportunity.

Worden approached his adversary on her starboard bow, on a course nearly at right angles with her line of keel, reserving my fire until near enough that every shot might take effect. I continued to so approach until within very short range, when I altered my course parallel with hers, but with bows in opposite directions [and] stopped the engine.

Lieutenant Greene was in the turret, and, as the two ships neared one another, he “triced up the port, ran out the gun, and, taking deliberate aim, pulled the lockstring.” And naval warfare was changed forever.

The two ships spiraled about one another, trading shots for quite some time, with neither able to strike a fatal blow. Their suits of armor withstood the terrible punishment each was attempting to inflict on the other. One Yankee witness on the nearby shore later remembered that “gun after gun was fired by the Monitor which was returned with whole broadsides by the rebels with no more effect, apparently, than so many pebblestones thrown by a child.” Within the ironclads, the shots striking the metal did not sound like pebblestones; the din inside both vessels was almost unbearable as striking shot reverberated throughout their echo-chamber hulls.

The spirals grew ever tighter until the two ships were next to each other, firing at point-blank range. And still the shots glanced off the Monitor’s whirling turret and off the Virginia’s sloping sides, causing no more than dents and the awful clatter. It was clear each had met her match, yet neither was able to prevail.

As Worden instructed the helmsman, “Keep her with a very little port helm, a very little,” there was a great flash and a thunderous crash as an enemy shell slammed into the pilothouse. Worden took much of the blast full in the face, and his eyes were filled with smoke and burning powder. He staggered back with his hands to his face and said, “My eyes. I am blind!” With blood pouring from all the pores of his upper face, he was taken to his cabin.

Greene was summoned to the pilothouse, but for a time, Seaman Williams, who had avoided serious injury, was handling the ship alone; he would be awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions. Greene took command and continued the fight.

By then, the two metallic contestants had fought for several hours, with neither ship suffering disabling damage. No one had been killed on either ship; only Worden was seriously injured. The Virginia had fought a battle with enemy ships the day before; the Monitor had fought a battle with the forces of nature that day as well. The result was that the men in both ships were exhausted, and the two vessels had expended much of their ammunition. It was time for this undecided but historic battle to end. The Virginia headed for Sewell’s Point, and the Monitor returned to her anchorage.

The Aftermath

When Abraham Lincoln heard that Worden was recuperating in a friend’s home in Washington, the President hurried to the house. Worden, his eyes still bandaged, heard Lincoln’s voice and said, “Mr. President, you do me great honor by this visit.” Lincoln paused a moment, then said, “Sir, I am the one who is honored.”

Worden never fully recovered from his wounds, suffering chronic pain, a blind eye, and permanent facial markings, but he returned to duty, commanding another ironclad, the Montauk, as part of the blockade that was strangling the Confederacy. In early 1863, he sank the Confederate raider Nashville, and he later participated in the ironclad attack on the forts guarding Charleston.

Because of his junior status, Greene was relieved of command of the Monitor soon after the battle but continued to serve as her executive officer, later participating in the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff on the James River. When the Monitor foundered in a gale 20 miles off Cape Hatteras on New Year’s Day 1863, Greene barely survived after being pulled into a lifeboat by the ship’s surgeon. He subsequently served in the gunboat Florida on the blockade off North Carolina and later sailed around South America and into the Pacific in the sloop Iroquois in search of the Confederate raider Shenandoah.

In a letter to his parents, Greene revealed that his roommate at the Naval Academy, “Buttsy” [Walter R. Butt], had been serving in the Virginia during the battle, adding “little did we ever think at the Academy, we should be firing 150 lbs. shot at each other, but so goes the World.”

A Reunion

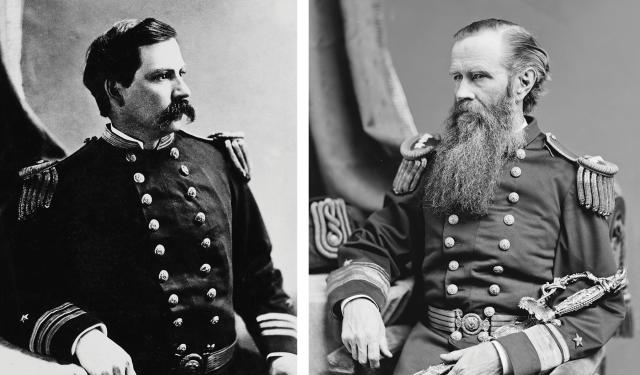

As fate would have it, John Worden and Samuel Greene would be reunited a decade later when both men were assigned to the U.S. Naval Academy. Worden, by then a rear admiral, had taken the helm as superintendent and was joined by then-Commander Greene, serving as head of the Department of Astronomy, Navigation, and Surveying.

The year 1873 was not a happy time for naval officers. In the decade following the Civil War, while other nations had learned the rather obvious lessons proffered by the duel between the Monitor and Virginia and were building steam-powered, ironclad ships, the U.S. Navy sold off or laid up much of what had been the world’s second-most-powerful fleet. In addition to those revolutionary concepts tested by the contestants at Hampton Roads, there had been other naval technological developments with rams, mines, torpedoes, and submarines that were embraced by many other nations, yet the U.S. Navy remained stagnant and would have been more appropriate for service in the 1840s. In 1873, during the so-called Virginius Affair—a diplomatic dispute among the United States, the United Kingdom, and Spain—it became clear, and alarming, that no U.S. Navy ship could have challenged a Spanish ironclad then showing her nation’s flag in New York Harbor.

In addition to this poor state of affairs, a seniority-based officer promotion system that had the effect of stagnating promotions had caused serious morale problems in the officer corps. So, it is not too surprising that a group of officers then serving at the Naval Academy decided to take action that some would consider bold and innovative—others would wonder if it were something akin to mutiny.

In the early twilight of 9 October 1873, the sounds of leather boots on cobblestones converged on one of the Naval Academy’s academic halls. Fifteen naval officers, ranging in rank from lieutenant to rear admiral, had come to “organize a Society of the Officers of the Navy for the purpose of discussing matters of professional interest.”

It is not clear who first conceived of the idea, though there are some indications it may have been Commodore Foxhall Parker, who had served in the Union Navy during the war while his brother had been Superintendent of the Confederate States Naval Academy. Another key player was Lieutenant Charles Belknap, who apparently organized the first meeting and subsequently served as secretary.

It is clear that Rear Admiral Worden presided over the meeting and was joined by his old shipmate Commander Greene. The rest of the group consisted of another commander, Edward Terry, Chief Engineer C. H. Baker, Medical Director Philip Lansdale, Pay Inspector James Murray, Lieutenant Commanders E. Harrington, J. E. Craig, Caspar F. Goodrich, P. H. Cooper, and C. J. Train, Lieutenant Willard H. Brownson, and Marine Corps Captain McLane Tilton.

The members of this eclectic group could not have known that they were creating a truly unique and enduring organization that would provide an open and independent forum for constructive—if sometimes critical—discussions of matters of great importance to the Sea Services and to the nation. They had laid the keel that would serve as the basis for two important magazines that would emerge to inform and record, as well as a book publishing press that would provide Naval Academy textbooks as well as guides and manuals that would help service professionals in the performance of their duties and would serve as the primary source of naval history among all publishers.

From that seemingly innocuous gathering would emerge other capabilities—such as podcasts, blogs, newsfeeds, and various forms of symposia—that would enhance the forum in ways that these men who were still relying on gas lighting and candles for illumination could not have predicted. Essay contests and oral histories became important contributions that further enhanced the mission, early decided as “the advancement of professional and scientific knowledge in the Navy,” later expanded to include the other Sea Services and adding the word “literary.”

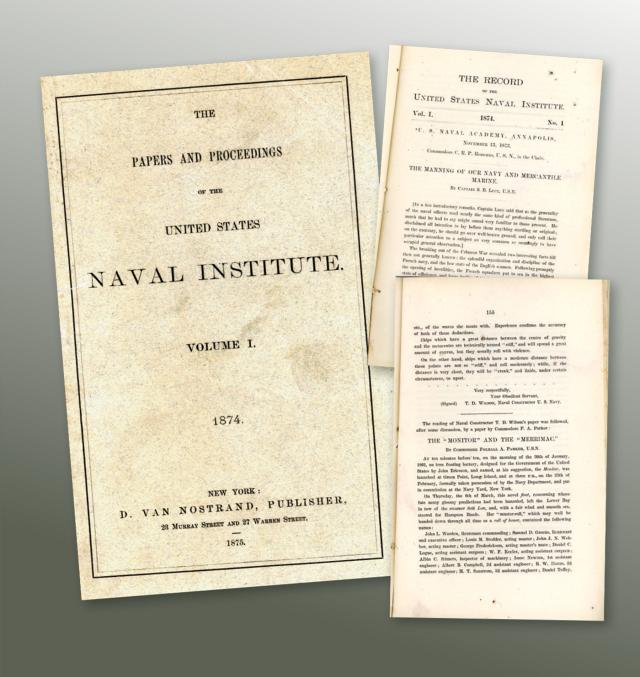

It did not take long for the organization to take shape and the membership to grow. By the end of the year, there had been four meetings, and new members included such luminaries as Stephen B. Luce of Naval War College fame and C. R. P. Rodgers, then Chief of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and future superintendent of the Naval Academy on two separate occasions.

They decided that their newly formed organization would be called the “United States Naval Institute,” a name that was certainly appropriate (if one assumes “naval” includes the Marine Corps and Coast Guard) but would sometimes lead to confusion by causing outsiders to assume it was a government entity. That it began at the Naval Academy and has continued to reside there on federal property (with the approval of Congress) for its entire existence of nearly 150 years has only added to the confusion.

The group decided to meet in the evening on the second Thursday in each month. They also decided to publish The Papers and Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute, later mercifully shortened to Proceedings. Included in the first issue was a paper presented by Commodore Parker titled “The ‘Monitor’ and the ‘Merrimac,’” which praised “Worden and his gallant men” and concluded with the words, “May a grateful country never suffer their memories to grow cold, and may their names, inseparably connected with some of the darkest and yet most glorious days of the Republic, be mentioned with reverence by our children’s children.”

In that same issue, the lead article was a paper presented by Commodore Luce at the 13 November meeting titled “The Manning of Our Navy and Mercantile Marine.” Arguing for a system of apprentice training in the Navy and the Merchant Marine, Luce’s paper spurred Congress to pass legislation supporting merchant marine training, naval apprenticeships, and the opening of the first state maritime school in New York City. This was just the beginning of important changes initiated by discussions in Proceedings. Over the ensuing years, forum contributors included many whose names would later adorn buildings and ships—Alfred Thayer Mahan, Ernest J. King, Chester Nimitz, Arleigh Burke, Edward L. Beach, and Elmo Zumwalt, to name a few. But of equal importance were the contributions of those of lesser rank and prominence, whose ideas—some of them game changers—would never have seen the light of day without the uniquely independent forum of the Naval Institute.

After nearly a century and a half, the importance of the Naval Institute is well established. Despite its unorthodoxy, it is the envy of the other services that have no such entity, and it continues to serve its original purposes and many more. Many of its ties to the Naval Academy remain in place but are largely overshadowed by its importance as an independent, professional military association whose mission transcends political affiliations and supports those who serve through its books, articles, conferences, and online content.

Legacy

In a moment of high drama in the waters of Hampton Roads, John L. Worden and Samuel Dana Greene fought for their nation’s very survival. Through their actions and those of countless others, a nation was saved and purged of an evil that threatened its ideals. Years later, in a less dramatic but unquestionably important way, these same two men and 13 others gathered in the contemplative surroundings of an academic lecture hall and again changed the course of history.

By creating an open and independent forum in which the exchange of ideas could lay siege to those fortifications that too often obstruct progress, they encouraged those who would dare to “read, think, speak, and write” for the betterment of that same nation that still strives to live up to its high ideals. These two men understood the significance of both the sword and the quill that are at the center of the Naval Institute’s insignia, and through their actions they helped preserve and defend the nation they selflessly served.

Sources:

Robert M. Browning Jr., “The Last Union Survivor,” Naval History 26, no. 2 (April 2012).

LCDR Thomas J. Cutler, USN (Ret.), “Duel of Iron,” Naval History 18, no. 4 (August 2004).

William C. Davis, Duel Between the First Ironclads (New York: Doubleday, 1975).

LT Samuel Dana Greene, USN, “Voyage to Destiny,” Naval History 21, no. 2 (April 2007).

COMO Foxhall Parker, USN, “The ‘Monitor’ and the ‘Merrimac,’” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 1, no. 1 (December 1874): 155–62.

John V. Quarstein, “The Monitor Boys,” Naval History 26, no 2 (April 2012).

Fred Schultz, “Influence and Relevance,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 139, no 10 (October 2013).

CAPT Roy C. Smith III, USN (Ret.), “The First Hundred Years Are . . .” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 99, no. 10 (October 1973): 50–76.

Richard Snow, Iron Dawn: The Monitor, the Merrimac, and the Civil War Sea Battle that Changed History (New York: Scribner, 2016).

G. V. Stewart, “An Admirable Servant, Occasionally Obsequious,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 74, no. 10 (October 1923): 1,199–211.

John L. Worden, Samuel Dana Greene, and H. Ashton Ramsay, The Monitor and the Merrimac: Both Sides of the Story (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1912).