In the world of naval warfare, the winds of change were well astir by the early 19th century. In 1784, Henry Shrapnel had invented an exploding artillery shell. In 1788, the first small steamship had launched, and by 1816 Robert Fulton was delivering his first steam-powered warship to the U.S. Navy. By 1820, an iron steamer was crossing the English Channel.

But all these noteworthy advances, these glimpses into the naval future, were not mainstream . . . yet. And so it was that in 1827, when the fleets of five nations clashed in a battle that would alter the course of a revolution and upset the fragile post-Napoleonic balance of power in Europe, it would be an epic blowout of the old school.

The Battle of Navarino, fought on the west coast of the Pelopponese on 20 October 1827, featured an alliance that would have seemed unthinkable a decade or so earlier: the Royal Navy and the French Navy, longtime arch-foes, now arrayed in common cause. With them sailed the Russian Navy, the three fleets united in a vainglorious hope to maintain the geopolitical status quo while at the same time curtailing the brutality into which the dragged-out Greek Revolution had devolved.

The Ottoman sultan had recruited Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt to help clamp down on the Pelopponese, and atrocities ensued, leading to the arrival of the triple-alliance fleet at the Bay of Navarino on 20 October. Vice Admiral Sir Edward Codrington, one of Nelson’s captains at Trafalgar, was in command, and now, on the eve of the anniversary of that great victory, he was about to engage in another battle that would determine the fate of nations.

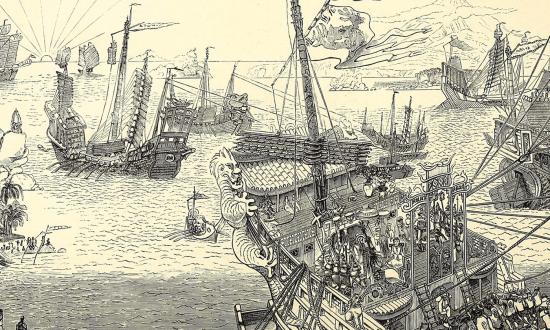

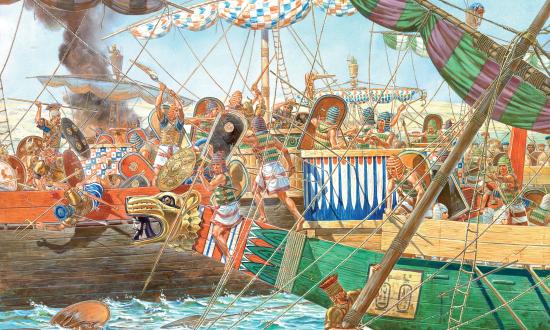

As the allies entered the bay, they found themselves facing a combined Turco-Egyptian fleet, superior in ships, men, and firepower, anchored in a curving horseshoe-shaped line. Codrington’s ostensible directive was to present a show of force, not start a fracas. But a British captain spied Turkish fireships being made ready; he ordered a pinnace to approach and warn them to desist. The Turks fired on the pinnace and lit one of the fireships. A cutter was sent to intercept the fireship. The Turks fired on the cutter. British and French ships fired back, and within minutes an all-out slugfest had erupted.

A British seaman on board the 60-gun HMS Genoa, which would suffer the most killed of the allied ships, recalled how his lieutenant “drew his sword and told us not to fire till he ordered. . . . Then crying out, ‘Stand clear of the guns,’ he gave the word ‘FIRE!’ and immediately the whole tier of guns was discharged, with terrific effect, into the side of the Turkish Admiral’s ship that lay abreast of us. After this it was, ‘Fire away, my boys, as hard as you can!’”

For four hours, the fleets blasted away at one another. With maneuver compromised by ships being at anchor, there was little in the way of tactical movement—just a relentless shooting match.

“The first man I saw killed in our vessel was a marine,” recounted the Genoa seaman. “He was close beside me . . . and on turning round I saw him at my feet with his head fairly severed from his body, as if it had been done with a knife.”

While the Turco-Egyptian fleet had the enemy outnumbered, the allies’ superior gunnery dominated the day. Beneath the smoke-blackened sky, the bay had become a hell of dead and dying.

“The firing continued incessant, accompanied occasionally by loud cheers, which were not drowned even in the roar of artillery,” the seaman wrote, “but distincter than these could be heard the dismal shrieks of the sufferers, that sounded like death knells in the ear, or like the cry of war-fiends over their carnage.”

The Turkish and Egyptian fleets were destroyed; the allies lost not a single ship. The way had been blasted clear for eventual Greek independence—but in the complex chessboard politics of the day, even the allies were desultory about the victory.

But the fight itself lives on as a milestone, one that marks the poignant twilight of an entire age—for Navarino was the last great naval battle fought entirely under sail.

Sources:

Douglas Dakin, The Greek Struggle for Independence, 1821–1823 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1973), 226–30.

William James, The Naval History of Great Britain: From the Declaration of War by France in 1793 to the Ascension of George IV, vol. 6 (London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd., 1902), 358–422.

Charles M’Pherson (identified as “A British Seaman”), Life on Board a Man-of-War, Including a Full Account of the Battle of Navarino (Glasgow, Scotland: Blackie, Fullarton, & Co., 1829), 136–37.

C. M. Woodhouse, The Battle of Navarino (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1965), 17–34, 110–41.