By the late 13th century, the great Mongol Empire held the whip hand from the fringes of Europe to the Sea of Japan. Genghis Khan and his successor-sons had mastered like none before the ruthless science of conquest. Brilliant horsemen, expert archers, geniuses at siegecraft, the Mongol armies were an inexorable tide, destined to carve out the largest contiguous land empire in world history. But along their southeastern marches there remained another empire—dazzling, more ancient, tantalizingly coveted—that so far had eluded their grasp: China.

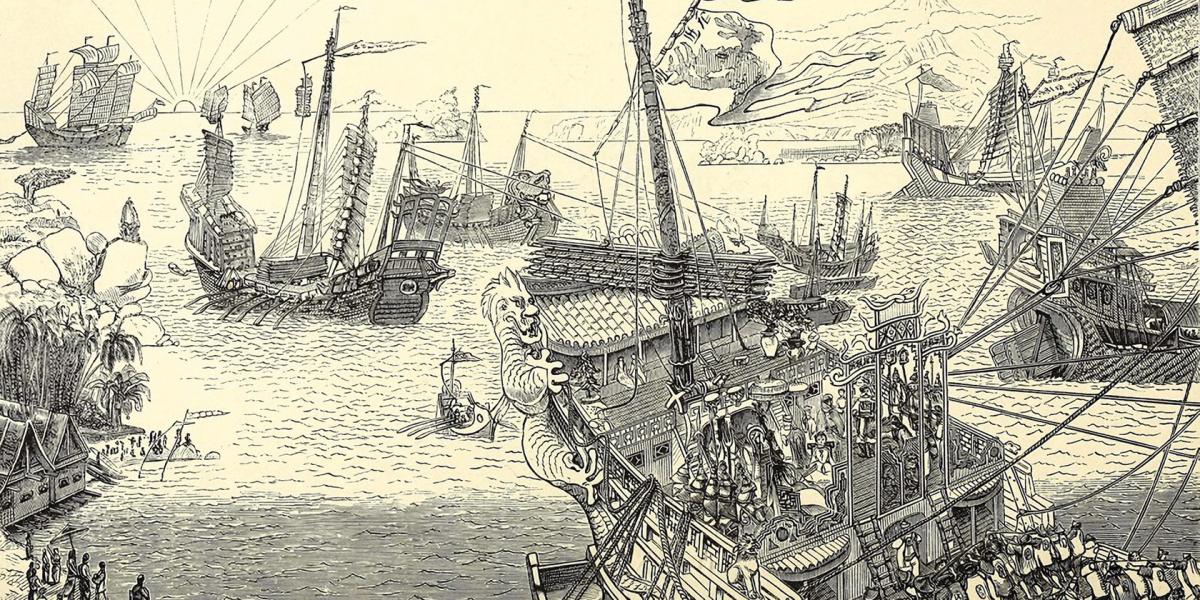

There, the Song Dynasty had ruled since 960, overseeing an age that witnessed a flowering of art and science. Song Dynasty China’s achievements included impressive strides forward in the naval realm: Paddle-wheeled warships, bedecked with trebuchets capable of catapulting incendiary payloads, plied the pirate-infested southern coast and the great inland river-highways. Song China’s advanced culture boasted a concomitantly advanced navy.

But by the 1260s, beneath that shining veneer there was creeping rot. And when a Chinese defector was lured to the court of Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan, he came with valuable insights: The Song fleet was wallowing in disrepair, thanks to corrupt government officials diverting naval funds to line their own pockets. China was ripe for the taking—if Kublai Khan could build a navy.

Such an undertaking was alien to the Mongols. As recently as 1251, the most advanced form of river crossing they could handle amounted to inflated animal skins and crudely constructed rafts. But Kublai Khan recruited talent from the far corners of his multi-ethnic empire and began constructing a fleet, augmenting the buildup with vessels captured as battle spoils in 1265. Starting thus from scratch, the speed with which the Mongols rose to a threatening level of naval capability was astounding. Now, instead of futile attempts at conquering China by land power alone, the Mongols would invade by way of the mighty waterways that led deep into the heart of Song territory.

The Han River bastions of Xiangyang and Fangchen fell in 1272. By 1275, the Mongols were on the Yangtze River. By 1276, the Song Dowager Empress was urging capitulation. The imperial capital fell; the nut had been cracked—but not entirely: The Southern Song, the remnant shred of the dynasty, held steadfast, and the Mongol victory would not be utter until South China fell as well.

Pushed ever farther to land’s edge, their armies decimated in one fight after another, the vestiges of the imperial entourage found themselves cornered at last near Guangdong, on the coast of the South China Sea. Here, in March 1279, came the final showdown: the Battle of Yaishan (aka the Battle of Yamen).

The fleet of the Southern Song admiral, Zhang Shijie, outnumbered that of the Mongols by ten to one. But despite his superior force, he fatally opted for a defensive position, while the Mongols’ admiral, Zhang Hongfan, was willing to carry the fight to the enemy.

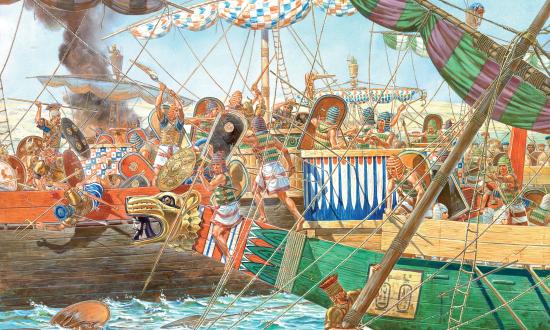

The Song admiral ordered 1,000 warships to be lashed together inside the bay at Yaishan to form a great floating wall. The Mongols sent in fire-ships, but the Chinese by now were inured to such tactics and had slathered their vessels in fire-retardant mud. Undaunted, Zhang Hongfang blockaded the bay, while Mongol land forces cut off the transport of water and supplies to the Chinese fleet. Deprivation, and desperation, began to set in, with those on the trapped ships resorting to drinking seawater.

When the full-on Mongol assault came, it hit the defenders from multiple directions. Despite its greater numbers, the Chinese fleet was crippled by its self-imposed entrapment and lack of individual vessel maneuverability. Rocks and arrows filled the sky as Mongol forces bounded onto the enemy’s floating palisade, brandished swords, and hacked their way through the sick and weakened foe, working their way ever closer to the center, toward the imperial barge that carried the last of the line, the boy-emperor Zhao Bing. The prime minister, seeing that all was lost, took the seven-year-old in his arms and plunged with him to a watery death.

The Mongols, upstart seafarers, had wiped out a vaunted naval power. Kublai Khan became the first Mongol emperor of China, the Yuan Dynasty supplanted the Song, and the Yuan navy would continue to grow, expand, and sail farther outward in search of new conquests. In mere decades, the Mongols had gone from animal skins and rafts to rulers of the waves—a stunning historical example of how quickly a new sea power can emerge.

Sources:

Thomas J. Craughwell, The Rise and Fall of the Second Largest Empire in History: How Genghis Khan’s Mongols Almost Conquered the World (Beverly, MA: Fair Winds Press, 2010), 224–47.

Lo-Jung Pan, China as a Sea Power, 1127–1368, Bruce A. Elleman, ed. (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2012), 211–46.

Stephen Turnbull, Fighting Ships of the Far East (1): China and Southeast Asia, 202 BC–AD 1419 (Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2002), 4–9, 14–36.

James Waterson, Defending Heaven: China’s Mongol Wars, 1209–1370 (London: Frontline Books, 2013), 224–36.