On 8–9 August 1942, the U.S. Navy suffered its worst defeat in combat at the Battle of Savo Island. The misapplication of technology, doctrine, and tactics allowed a well-trained and disciplined Japanese cruiser force to decimate a larger group of Allied cruisers and destroyers defending amphibious forces off Guadalcanal.

One year later, using nearly the same technologies but a different tactical doctrine, a U.S. destroyer force reversed the prior result. On the night of 6–7 August 1943, Commander Frederick Moosbrugger, commanding a task force of six U.S. destroyers, intercepted a Japanese flotilla in Vella Gulf, Solomon Islands, sinking three of the four enemy destroyers with no damage to his force (see “‘Perfect in Every Respect,’” August 2008, pp. 26–33). This signal victory was the first use of tactics devised as a result of studying the fighting at Savo Island and the battles that followed in the latter half of 1942.

U.S. and Japanese forces fought 13 major surface actions prior to the Battle of Vella Gulf, with the results tilted heavily toward the Japanese. Starting with Moosbrugger’s victory at Vella Gulf, all but one of the subsequent surface actions in the Solomons were resounding U.S. victories. But it had taken 12 long months of U.S. sailors dying to apply the lessons of those earlier battles.

Transition to Wartime Doctrine

Historian Trent Hone (author of “Guadalcanal Quintet,”) has written extensively on the development of U.S. Navy tactical doctrine in the interwar period and throughout World War II, including critiquing the execution and evolution of night-fighting doctrine during the Guadalcanal campaign. This essay stipulates Hone’s assertions about the flaws of prewar small-battle tactics (“minor tactics”) along with his reluctance to blame prewar planning for the Navy’s tactical woes.

Hone points to the summer of 1943’s landmark Current Tactical Orders and Doctrine, U.S. Pacific Fleet, PAC 10 as proof that the U.S. Navy put deliberate effort into developing a battle doctrine that incorporated “major tactics”— tactics for a large fleet in battle—and minor tactics, with lessons from the first year of combat.1 But the Navy had been lethargic in reviewing lessons from the night actions of 1942 and promptly applying those lessons.

During the interwar years, the Navy spent significant time and energy planning for a future war. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz famously stated after World War II that “the war with Japan had been enacted in the game rooms at the War College by so many people and in so many different ways that nothing that happened during the war was a surprise—absolutely nothing except the kamikaze tactics toward the end of the war. We had not visualized these.”2 But perhaps that sentiment was more nostalgia than history. Or more critically, once the war began, “so many people” turned their attention to the crisis at hand and lost their focus on which of the “many different ways” worked and did not work for surface navy doctrine.

The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor significantly disrupted U.S. plans for the employment of the Pacific Fleet. The fleet had not considered nor trained for operating without the battleships that were lost in the 7 December 1941 attack. Most of the interwar Fleet Problems had focused on major tactics—employing the battle line as the central part of the fleet; minor tactics mainly focused on support of the battle line. When the remaining surface fleet was called into action in 1942, the prewar lack of emphasis on minor tactics showed, and the results were less than spectacular.3

The first indications that the Navy was unprepared for surface combat against the Japanese occurred in the opening months of the war. Isolated in the western Pacific, the ships of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet fought bravely with the ill-fated American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM) in defense of the Malay Barrier. The outnumbered ABDACOM was soundly defeated at the Battle of the Java Sea on 27–28 February 1942 and the Battle of Sunda Strait the next night. While initial torpedo salvos and gunnery were poor on both sides, the decisive blow at Java Sea was a devastating night torpedo attack by Rear Admiral Takeo Takagi’s heavy cruisers that sank two Dutch cruisers, which joined the three Allied destroyers lost earlier in the battle on the bottom of the Java Sea. The Japanese suffered only one destroyer damaged.4

Unfortunately, even though the Asiatic Fleet commanders wrote detailed reports of the actions of January and February 1942, the lessons from this devastating defeat were not developed and pushed to the fleet until more than a year later, in March 1943—months after significant U.S. losses in the naval battles around Guadalcanal.5

‘To Know Tactics Is to Know Technology’

After the victory at Midway in June 1942, U.S. forces tentatively took the offensive in the Pacific with the invasion of Guadalcanal and Tulagi islands that August. The initial naval defense of the landings fell to the 8 cruisers and 15 destroyers of the invasion escort and fire support groups under the command of Royal Navy Rear Admiral Victor A. C. Crutchley. On the night of 8 August 1942, this force was disposed in three separate groups to cover the three entrances to Sealark Sound (later known as Ironbottom Sound), where the transports of the invasion force continued to offload men and supplies.

Despite the demonstration of Japanese naval tactics during night surface actions earlier in 1942, Allied naval commanders still did not fully understand their foe. Nor did they fully understand their own forces’ capabilities. The lack of a unified doctrine, despite the eight months since the loss of the battle line at Pearl Harbor and the Asiatic Fleet’s experience, resulted in a poor disposition of forces and the failure of individual ships to remain vigilant for the enemy’s unexpected arrival. No coordinated action was planned in advance of contact with the enemy, and “no provision can be found in [the western screening force’s] instructions for night action in the event of a surprise raid by enemy surface ships detected only after they had gotten within gun range.”6

The late naval strategist Captain Wayne Hughes’s six cornerstones of naval tactics include, “To know tactics is to know technology.”7 While interwar weapons designers worked hard, building new and better guns and radar, the tacticians did not keep up. The Japanese developed their technology as well, focusing on the Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedo and night optics instead of radar and guns. The fundamental difference between the two adversaries was the coordination between the technology and the tactics. At Savo Island, the Navy relied on a technology that was not fully understood—radar—to overcome a lack of coherent tactical doctrine, and the technology failed to deliver.

Radar was first deployed on board U.S. warships in 1938, but the ships of the Asiatic Fleet were not equipped with it. Having radar available at Guadalcanal would appear to give the Americans an advantage over the Japanese. But dependence on radar failed to overcome Japanese night-fighting tactics.

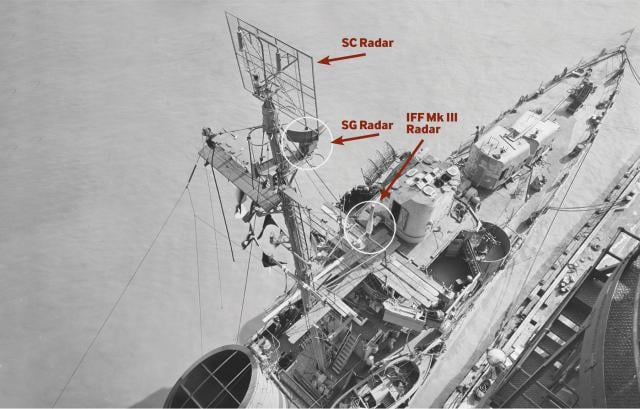

The SC radar on board the two picket destroyers east of Savo Island was manually trained, and its displays were relatively primitive. An operator had to verbally communicate contact reports to the ship’s command team, stationed in a different part of the ship. The maritime environment in the South Pacific, which differed greatly from the North Atlantic, where initial SC radar testing had been accomplished, also significantly reduced detection ranges and sensitivity, unbeknownst to U.S. commanders. Lack of knowledge about radar meant a lack of trust among more senior naval officers throughout the subsequent battles around Guadalcanal. Even Commander Arleigh Burke, who would learn to capitalize on the radar advantage, hesitated in his first action against the enemy because of his mistrust of the information provided by his radar operator.8

The Allied force at Savo Island, and throughout the Guadalcanal campaign, was equal to or superior to the Japanese in guns, radar, and overall ship technology. But the Japanese Navy’s comprehensive and well-understood doctrine overcame these technological advantages.9 The U.S. Navy needed a new doctrine, not new ships or new technology.

Failure to Learn the Lessons of Savo Island

The Allies did little, if anything, to address the causes of their defeat at Savo Island in the ensuing months. To be sure, the Navy had some success in the subsequent battles around Guadalcanal. Still, on the whole, it failed to develop a tactical doctrine to counter Japanese torpedo attacks or take full advantage of radar. In the year following the Battle of Savo Island, no fewer than six major surface actions occurred in the South Pacific, resulting in the loss of 9 U.S. warships, damage to 13 others, and the deaths of more than 2,000 sailors.10 Yet the lessons learned at Savo Island did not reach the fleet until March 1943.11

After the 13 November 1942 First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, Rear Admiral William S. Pye, president of the Naval War College, wrote a scathing critique, noting:

We study the reports of actions, in order to learn lessons from them so that they may not be repeated. Yet the statement is made that this condition has grown progressively worse. Surely some thing, or person, or policy has been responsible for it; if so, nothing has been stated as to what is being done to remedy it.12

Pye called flag officers to task for the piecemeal introduction of ships into battle and the complete failure to apply lessons from the previous battle to the next. Of the five major surface actions fought in the four months after Savo Island, none were led by the same U.S. flag officer, and few of the ships fought in more than two of the battles. Lessons on the proper deployment and use of radar-equipped ships were not absorbed. Continuing his critique of the 13 November battle, Admiral Pye lamented:

It seems also generally accepted that the American force went into this action without any battle plan, without any indoctrination, or understanding between the OTC [officer in tactical command] and his subordinates; with incomplete information as to existing conditions in possession of subordinates. . . . Destroyers were tied to the column rigidly—practically used as ships of the line, which is not their function. . . . The OTC and the unit commanders were not on the ships with the best radar equipment.13

New Eyes on an Old Problem

In 1943, as momentum shifted toward a broader offensive and more forces flowed from the United States, U.S. naval leaders had the time and inclination to analyze the previous year’s naval combat and look for ways to improve performance. One of those new to the fight was Commander Burke. He was an engineer by training, and his technical assignments had kept him away from the interwar Fleet Problems. He had to beg his way into a combat command in 1943, and he had to make up for his lack of seagoing experience. He did what all engineers do: study. He examined the surface actions around Guadalcanal and concluded that several things had to change.14

Burke recognized that “by fighting in long columns to maximize gunfire effectiveness, the cruisers and destroyers were vulnerable to a salvo of Japanese Long Lance torpedoes,” notes Wayne Hughes. “Burke developed tactics that exploited our first-detection surface radar advantage to make sudden surprise attacks in two short columns, each one holding gunfire while first firing our own torpedo salvos as the decisive weapon.”15

By recognizing the U.S. technological advantage of radar and applying it to a common tactical doctrine, Burke’s ideas ensured that the Navy would be prepared to fire first effectively, and thereby negate the Japanese night-fighting doctrine.

New Tactics, New Success

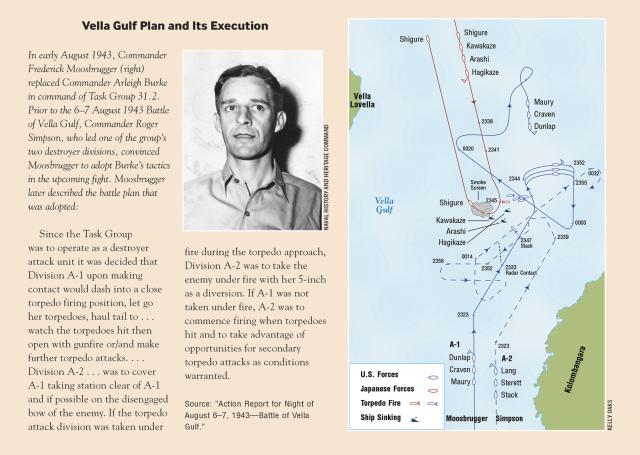

The first opportunity to use the new tactics occurred a year after the Battle of Savo Island. Commander Moosbrugger, using Burke’s tactics, led two three-ship destroyer divisions of Task Group (TG) 31.2 into Vella Gulf to intercept a Japanese four-destroyer resupply mission.16 Before TG 31.2 departed Tulagi on 6 August 1943, he held a conference with all commanding officers. “The Battle Plan was discussed and information exchanged,” the commander later reported. “This conference was of great value as it enabled any doubtful points to be cleared up. There was complete mutual understanding of all possible situations to be encountered.”17

Moosbrugger’s plan applied all the lessons learned from the previous year’s surface actions and incorporated Burke’s recommendations for effective use of the destroyer’s main battery of torpedoes.18

Just as the Japanese had done at Savo Island, Moosbrugger’s force was able to strike with ship-killing torpedoes before detection by the opposing force. Executing the plan precisely as briefed, the task group sank three Japanese destroyers. A fourth was hit by a dud and escaped. Moosbrugger’s six destroyers returned unscathed to Tulagi.

The success at Vella Gulf was not because of any significant improvement of technology, but instead improvement in the manner in which technology was employed. Moosbrugger’s ships were all of prewar vintage, and most had fought throughout the battles of the Solomons campaign. Individual ship performance benefited from the implementation of the combat information center (CIC) concept.19

The CIC brought together technology and the decision-makers and allowed commanders to take full advantage of information available from the more reliable SG radars installed on the ships since their initial arrival in the Solomons.20 At the task group level, using radar for long-range detection but withholding position-revealing gunfire until after torpedo attack runs, Moosbrugger took full advantage of the technology at hand. Knowing the full capability of the ships’ weapons systems and sensors, and then communicating a common plan to all commanders, Task Group 31.2 executed a near-perfect surface engagement.

Over the next four months, three more surface battles occurred in the Solomon Islands chain. The 6–7 October 1943 Battle of Vella Levella was a tactical draw because of an impatient attack by an outnumbered U.S. destroyer force. Rear Admiral Aaron S. “Tip” Merrill and Burke finally were able to bring the entire cruiser-destroyer force to bear at the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay on 1–2 November. Cruiser Division 12’s four Cleveland-class light cruisers and Destroyer Squadron 23’s eight Fletcher-class destroyers represented the latest in U.S. warship design. Using Burke’s new, coordinated cruiser-destroyer tactics, this force decisively defeated Admiral Sentaro Omori’s similarly sized cruiser-destroyer force, sinking or heavily damaging four of four Japanese cruisers and two of six Japanese destroyers, at the cost of only two U.S. ships lightly damaged.

Three weeks later, Burke’s Destroyer Squadron 23 executed what is often called an “almost perfect action” off Cape St. George, New Ireland. With two supporting columns of destroyers, Burke detected Captain Kiyoto Kagawa’s two escort destroyers on radar and closed in undetected for a torpedo attack, sinking both ships. The loss of their escort forced Kagawa’s three transport destroyers to flee, preventing the planned resupply of Buka Island. This was the last surface engagement of the Solomon Islands campaign.

The Lesson: Assess and Adjust

Present-day U.S. Navy leaders work diligently to predict the tactics required for the next war, but naval officers at all levels must be prepared to assess the results of initial combat rapidly and to adjust doctrine accordingly. To do this, they must know the technology of their systems, including capabilities and limitations, and be prepared to exploit their systems’ abilities, even if they are not what they were designed to do. If the Navy expects to exploit its asymmetric advantage of rapid decision-making and flexible operational doctrine, it must inculcate in its leaders the need to rapidly identify, communicate, and implement lessons of naval combat once a war begins.

1. Trent Hone, “U.S. Navy Surface Battle Doctrine and Victory in the Pacific,” Naval War College Review 62, no. 1 (Winter 2009): 75. See also, Trent Hone, Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 1898–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018); Trent Hone, “‘Give Them Hell!’: The U.S. Navy’s Night Combat Doctrine and the Campaign for Guadalcanal,” War in History 13, no. 2 (April 2006).

2. FADM Chester W. Nimitz, USN, speech to Naval War College, 10 October 1960, folder 26, box 31, RG 15 Guest Lectures, 1894–1992, Naval Historical Collection, Naval War College, Newport, RI.

3. Hone, “‘Give Them Hell!,’” 174, 177.

4. Naval History and Heritage Command, “The Last Battle of USS Houston, Sunda Strait, 28 February–1 March 1942,” 30 March 2017.

5. See ADM Thomas C. Hart, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Asiatic Fleet, and RADM William Glassford, Commander, Task Force 5 of the Asiatic Fleet, The Java Campaign (Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence, 1943).

6. Richard W. Bates and Walter Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, August 9, 1942: Strategical and Tactical Analysis (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College, 1950), 56.

7. CAPT Wayne P. Hughes Jr. and RADM Robert P. Girrier, USN (Ret.), Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 3rd ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press: 2018), 23–24.

8. E. B. Potter, Admiral Arleigh Burke: A Biography (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1990), 72.

9. Bates and Innis, The Battle of Savo Island, 105.

10. Summary of action in the waters surrounding Guadalcanal derived from Samuel Eliot Morison, History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 5, The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942–February 1943 (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1949).

11. Battle of Savo Island and Battle of the Eastern Solomons, Publications Branch (Washington, DC: Office of Naval Intelligence, 1943).

12. The President, Naval War College, to The Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, serial 2238, 5 June 1943, 7.

13. The President, Naval War College, to The Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, 4–5.

14. Potter, Arleigh Burke, 63.

15. CAPT Wayne P. Hughes Jr., USN (Ret.), “An Old Salt Picks His Four Favorite American Admirals—And Explains Why (II): Burke,” Foreign Policy, 3 April 2017.

16. Potter, Arleigh Burke, 85.

17. Commander, Destroyer Division Twelve, “Action Report for Night of August 6-7, 1943—Battle of Vella Gulf,” dtd 16 August 1943, 1. Available at ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ships/logs/DD/desdiv12-430809.html.

18. “Action Report for Night of August 6-7, 1943,” 4.

19. Commanding Officer, USS Craven (DD 382), to Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, “Vella Gulf Night Action of August 6-7, 1943—Report of,” dtd 8 August 1942, 5-6. After action reports from other ships at Vella Gulf also praise the performance of CIC.