Nonrigid airships or “blimps” or “gas bags” were a major component of U.S. naval aviation during World War II and through the 1950s. The largest “class” of blimps was the K-series.

The K-1 was an experimental blimp, built by the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia in 1931. Among the features she introduced was a “gondola” or “car” attached directly to the envelope. The K-1 had two tractor engines, a gas bag of 319,900 cubic feet, and a maximum speed of 65 miles per hour. That pioneer served in experimental and training roles until scrapped in 1941.

By that time, production was underway at Goodyear in Akron, Ohio, on the larger, faster, and more capable K-2 series, with the lead ship’s first flight on 6 December 1938. (The Navy took over all lighter-than-air operations in 1937, ending the separate Army and Navy efforts; the disposal of the Los Angeles [ZR-3] in 1939 marked the end of the Navy’s rigid airship program.)

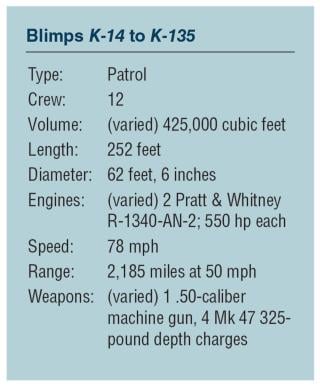

A total of 134 blimps of the K series was produced by Goodyear. By late 1942, the company was building five K-series blimps a year, and it reached peak production of 11 per month by mid-1943. There were several subseries, differing mainly in gas-bag size and engines. During World War II, the blimps were fitted with a .50-caliber machine gun and could carry four 325-pound depth charges.

Some K-series blimps were fitted with the ASG radar, which displayed returning echoes on a map-like position indicator; it had a range of some 90 miles for small surface objects. Also fitted was a magnetic anomaly detector (MAD) that could “sense” a submarine’s presence in relatively shallow water. MAD’s depth limitation required the blimp to fly rather low, and, of course, the system would respond to shipwrecks in shallow water.

During the war, the Navy blimps—mainly K ships—flew 37,000 patrols, most off the Atlantic coasts of North and South America, over the Caribbean, and, later in the war, over the Strait of Gibraltar and the western Mediterranean.1 The first nonrigid airships of any nation to cross the Atlantic were six K-series blimps that flew from South Weymouth, Massachusetts, via Newfoundland and the Azores to Port Lyautey (now Kenitra) in French Morocco during June 1944. The flight time for each of the three legs was about 20 hours. More blimps followed them across the Atlantic.

Those blimps searched for submarines in the relatively shallow waters around the strait using magnetic detection gear; later they were employed to locate mines at Mediterranean ports.

Blimp enthusiasts point out that not one ship was lost to U-boat attacks in convoys escorted by blimps. This is correct—but irrelevant. The problem is that every one of those convoys was escorted by surface ships, and some also had escort or “jeep” carriers with aircraft that sought out U-boats. It is difficult to prove a negative. However, the blimp-versus-submarine score during the war was Blimps = 0; German U-boats = 1.

That U-boat “kill” occurred on the night of 18–19 July 1943, when the K-32 and K-74 were on patrol over the Florida Straits. The destroyer USS Dahlgren (DD-187) also was on station in the straits. The two blimps detected the German U-134 with their radar, and the K-74 attacked. The U-boat remained on the surface and fought it out with the blimp.

Navy doctrine required blimps to stay out of range of surfaced submarines and to guide in aircraft or surface ships for the attack. The K-74’s pilot, Lieutenant Nelson G. Grills, attempted to prevent the U-134 from reaching a tanker and freighter steaming ahead of the submarine. The blimp fired about 100 rounds of .50-caliber ammunition before her machine gun was unable to depress sufficiently as the blimp passed over U-134 on her bombing run. The blimp released her depth charges, inflicting minor damage on the submarine.

The U-boat’s two 20-mm cannon, however, inflicted fatal damage on the blimp, which came down at sea. Abandoned by her ten-man crew, the wreckage of the K-74 remained afloat for several hours, with the U-134 pulling part of the wreckage onto her deck for photographs and examination.2 The airship’s crew, which took to rafts, was rescued some eight hours later, except for one man, reportedly attacked by a shark just prior to rescue.

Other U-boats were sighted by blimps, usually leading aircraft or surface ships to seek out and attack the undersea craft. And several blimps were lost operationally, most because of weather or mishandling.

A few K-series blimps also operated over the U.S. Pacific coast, primarily in the search-and-rescue role. One did attack a submerged submarine near San Francisco—a U.S. submarine!

The production sequence of the K-series blimps was not straightforward, with their numbers out of sequence with subseries. And, as aforementioned, their gas-bag size and engines varied with the subseries. After the war, some K-series blimps were extensively rebuilt, with significantly larger gas bags.

During the war, the K-series blimps were designated ZNP-K, with the “Z” indicating lighter-than-air, the “N” nonrigid, and the “P” patrol. Individual blimps were (usually) identified by a sequential numbers, as ZNP-K-2, etc. Invariably they were identified simply by their K-series designations. The postwar, rebuilt airships bore the series designations ZP4K and ZP5K, subsequently changed to ZSG-4 and ZS2G-1, respectively.

Did blimps contribute to the Allied victory over U-boats in the Battle of the Atlantic? Grand Admiral Karl DÖnitz, commander of U-boats and then head of the German Navy in World War II, wrote to blimp historian J. Gordon Vaeth:

It is possible that a U-boat commander, at the sight of a “blimp,” might conclude that a convoy was nearby. On the other hand, there was also the possibility that the sighted “blimp” was only on patrol. But even if the commander, upon seeing the “blimp,” surmised a convoy, that would only be a slight disadvantage to the use of a “blimp” since it would hinder the U-boat’s approach, at the very least severely.3

Significantly, however, it is difficult to find references to blimps in the multitude of U.S., British, and German histories of the Battle of the Atlantic.

And what was the cost of the airship effort? Could the expenditures for material and engines, the related industrial facilities, training efforts, special bases, and personnel—both air crews and dedicated ground crews—have been more effectively allocated to producing additional land-based patrol bombers and other antisubmarine aircraft? An objective analysis would indicate that, for the cost, more effective antisubmarine systems than the blimps could have been put into the war effort.

1. The definitive work on U.S. Navy blimps in World War II is J. Gordon Vaeth, Blimps & U-boats: U.S. Navy Airships in the Battle of the Atlantic (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1992).

2. The U-134 was sunk on 24 August 1943, near Vigo, Spain, by depth charges dropped by a British Vickers Wellington bomber. All 48 men in the submarine were killed.

3. Vaeth, Blimps & U-boats, 172.