Operation Desert Storm (17 January–28 February 1991) witnessed the U.S. Navy’s evolution from a force zeroed in on winning a war at sea with the Soviet Navy to one fighting continental campaigns as part of joint-service and multinational coalitions. Major changes to institutions with long-established and widely accepted strategic doctrines and methods of operation may prove beneficial over time. But the transitional process, like sausage-making, can be a messy affair. Such was the case with the Navy and Desert Storm.

The Reagan Buildup and the ‘Tanker War’

Because of President Ronald Reagan’s strong support and Navy leaders’ determined efforts during the 1980s, the fleet on the eve of the Gulf War was never more powerful. By 1990, the Navy had put to sea a sizable force of 15 carrier battle groups, four battleship surface action groups, 100 attack submarines, and many more combat and support ships. The fleet boasted the most technologically advanced aircraft, weapons, and ships, including the large-deck, 90,000-ton aircraft carriers of the Nimitz class and four recommissioned battleships of the Iowa class.

Surface ships and submarines gained the ability to project their conventional firepower hundreds of miles from the sea with Tomahawk land-attack missiles (TLAMs). Top-of-the-line aircraft included advanced variants of the all-weather, day-night A-6 Intruder attack plane, the

new F/A-18 Hornet strike fighter, and the F-14 Tomcat fighter. With their newly installed SPY-1A phased-array radars and Phalanx close-in weapons systems, Aegis guided-missile cruisers provided the fleet with strong antiair protection.

The Navy also deployed 3,650-ton Oliver Hazard Perry–class guided-missile frigates that operated highly versatile SH-60B Seahawk helicopters. Vice Admiral John B. “Bat” LaPlante, who led U.S. amphibious forces during Desert Storm, aptly observed that the Navy could not have achieved what it did in 1991 ten years earlier: “not on a bet; we got what we paid for in the Reagan years.”1

Joint-Service Reluctance

With the disintegration of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, that country’s navy largely disappeared from the world’s oceans. The U.S. Navy found itself without the maritime enemy it had been built to defeat in cataclysmic battles far from shore. At the same time, American strategists concluded that the U.S. armed forces would need to improve their ability to fight as a team and against enemy nations that usually possessed minimal maritime capabilities. That core idea was embodied in the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986.

As they had during the Cold War conflicts in Korea and Vietnam, however, many naval leaders resisted subordinating their aircraft carriers and Marine combat units to commands headed by Army or Air Force generals. As a consequence, the Navy provided only a small, woefully underpowered staff to serve as the naval component under Commander in Chief, Central Command (CINCCENT), and half-heartedly took part in joint military exercises. Secretary of the Navy John Lehman later complained that decision-making during the “Tanker War” was complicated by “Washington’s obsession with ‘jointness’” and reliance on U.S. Central Command’s (CENTCOM’s) “1,000 uniformed bureaucrats.”2 At the outset of Operation Desert Shield—the initial response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait—in August 1990, the Navy had to send to the Persian Gulf its Seventh Fleet commander, Vice Admiral Henry H. “Hank” Mauz Jr., and naval forces then operating thousands of miles away in the western Pacific.

Once on the scene, Mauz, a decorated Vietnam veteran and key commander during the Sixth Fleet’s strikes against Libya in 1986, took charge on board his flagship off Bahrain as Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Central Command. Despite the desires of the theater commander, Army General H. Norman Schwarzkopf Jr., naval leaders resisted deploying Mauz’s headquarters to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where he would be under the general’s close supervision. When Vice Admiral Stanley R. Arthur relieved Mauz on 1 December 1990, he considered moving his headquarters to Riyadh but did not for fear of disrupting his command’s preparations for combat, since war with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq was imminent.

Raising the Shield

Soon after the start of Desert Shield, the air wings of the carriers USS Independence (CV-62) and Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) were on hand to help defend the skies of Saudi Arabia.

As anticipated during the 1980s, soon after President George H. W. Bush ordered the U.S. military into action, Maritime Prepositioning Squadrons with ships carrying one month’s supply of war materials for two Marine expeditionary brigades deployed to the gulf. As a result, only weeks after Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait, strong Marine forces were on hand to defend Saudi Arabia’s ports and airfields.

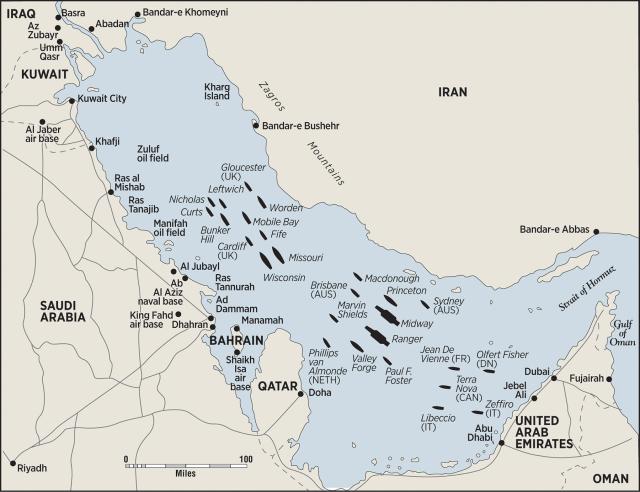

By the end of August, Mauz also had in theater two aircraft carriers with more than 300 combat planes, the battleships Missouri (BB-63) and Wisconsin (BB-64), and 25 other warships. The Navy’s preparation during the 1980s for the global sealift of powerful combat forces proved its worth. Speedy and specially configured fast sealift ships of the Navy’s Military Sealift Command (MSC) made repeated trips from the United States, delivering armored vehicles, helicopters, and other high-priority cargoes. The 96 cargo ships and tankers of the Ready Reserve Force fleet, while experiencing numerous operational difficulties, provided the bulk of the military gear and supplies flowing to Saudi Arabia.

Indeed, during the seven months of the Persian Gulf War, MSC delivered to the theater 95 percent of the armored vehicles, attack helicopters, trucks, heavy weapons, ammunition, and supplies for ten combat divisions.

The men and women of the 3rd Naval Construction Regiment—Seabees—along with Marine engineer units, built airstrips, logistic facilities, and ammunition dumps. Lieutenant General Walter E. Boomer, commander of the I Marine Expeditionary Force, remarked at the time that the Seabees “don’t talk a lot of bullshit. . . . They just go out and do the job.”3

As sanctioned by United Nations Resolutions 661 and 665, the U.S. Navy, with U.S. Coast Guard assistance, and the navies of 12 other nations mounted a major maritime interception operation to prevent Saddam from importing war materials and exporting his main revenue source, oil. As commander of the largest international naval contingent, Mauz coordinated monthly meetings with the heads of the other naval forces. They established protocols and procedures for hailing, stopping, and, if need be, seizing merchant ships sailing to and from Iraq. The international naval contingents carried out routine measures to enforce the embargo but also employed helicopters and specially trained boarding teams using novel “vertical insertion” and “fast-roping” techniques. The embargo patrol not only strangled Iraq’s overseas commerce, but also reassured the many nations involved that they were part of a righteous international effort to fight aggression.

Assault by Air and Sea

The Navy’s contribution was absolutely essential to the success of the Desert Storm air offensive that kicked off on 17 January 1991. Just before the opening shots, Arthur let the sailors and Marines in his command know he was “confident in your abilities, your courage and stamina.” He added, “we are joined by professional, talented allies with impressive skills, courage and dedication.” Paraphrasing a line from James Michener’s classic Korean War novel The Bridges at Toko-Ri, the admiral wondered, “Where do we get such [brave] men and women?” He observed: “I’m proud of each of you. Good hunting and God speed.”4

In the early morning hours of 17 January 1991, the battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and submarines deployed in the Persian Gulf, Red Sea, and Mediterranean launched salvos of Tomahawks at targets in the heavily defended Iraqi capital. While the Gulf War TLAMs lacked sufficient hitting power and accuracy, they still took a heavy toll on enemy facilities. In addition, five and later six aircraft carriers launched strikes from the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. As part of the allied aerial armada, the Navy’s carrier squadrons wreaked havoc on Iraq’s air defenses, communications facilities, airfields, naval bases, and power stations.

It is noteworthy that the Navy’s intelligence establishment helped the allies understand and neutralize Iraq’s air-defense system. Navy-launched HARMs (high-speed antiradiation missiles) took out many enemy radars, and carrier-based EA-6B Prowler electronic-countermeasures aircraft jammed others to protect allied aircrews. On the first night of Desert Storm, Lieutenant Commander Mark I. Fox and Lieutenant Nick Mongillo, pilots of F/A-18 Hornets operating from the carrier USS Saratoga (CV-60), shot down two enemy MiG-21 fighters over Iraq.

These were the only Navy kills of the war, however. Air Force General Charles Horner, CENTCOM’s Joint Force Air Component Commander (JFACC), was not confident that Navy planes had the right equipment to differentiate between friendly and enemy aircraft, so he limited their use in the air interdiction effort. On the other hand, Air Force and allied aircrews greatly respected the Navy-developed Sidewinder and Sparrow air-to-air missiles that proved instrumental to the coalition’s 38 aerial victories.

In “tank-plinking” strikes, Navy A-6 Intruder, A-7 Corsair, and F/A-18 Hornet attack planes and Marine AV-8 Harriers and Hornets devastated enemy armored forces in Kuwait with laser-guided bombs and other precision-guided munitions. While most of the ordnance dropped on the enemy forces in Kuwait consisted of Vietnam-era conventional “iron bombs,” air-to-surface missiles, and rockets, their use in day and night attacks thoroughly demoralized Iraqi troops miserably holed up in desert redoubts. Intruders and Corsairs, at the end of their service lives, performed well enough in Desert Storm, as did the Hornets.

Naval leaders recognized, however, that the F/A-18s would need future improvements to increase their range and ordnance-carrying capacity. The Harriers, vertical/short takeoff and landing planes able to operate from nearby ships and unimproved airstrips, were useful in low-level air-support missions. They proved vulnerable to Iraqi air-defense weapons, however, which shot down four of them during the Gulf War.

Only with a robust air-defense umbrella could U.S. and allied aircraft carriers, surface warships, and logistic vessels operate deep into the constricted Persian Gulf. Defending the allied armada were U.S. Aegis cruisers and multinational surface ships armed with surface-to-air missiles and coalition early-warning, patrol, and fighter aircraft. The one Iraqi test of the coalition’s air defenses proved to be the last when a Saudi air patrol shot down two enemy Mirage jets picked up on allied radars heading into the gulf. Navy radar-equipped surface ships and aircraft as well as Air Force AWACS (airborne warning and control system) planes ensured that no midair collisions of friendly aircraft occurred during the entire war.

Friction with Schwarzkopf, Air Force

The Navy’s transition from planning for a fight with the Soviet Navy to participation in joint operations involving the other services, especially the Air Force, did not go smoothly. General Schwarzkopf made it clear from the outset he wanted Horner, his JFACC, to control the aviation assets of the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy. Horner also made it clear he would not accept the Vietnam-era “route package” approach to bombing that created separate service-oriented zones. When Mauz suggested as much, Horner shouted: “F--- that! . . . We’re not going to do it! I’ll resign first.”5

The only major difference between Schwarzkopf and Arthur related to the destruction by Arthur’s forces of Iraqi tankers loaded with flammable petroleum off the coast of Kuwait. The admiral believed Schwarzkopf had authorized their sinking to lessen the danger to coalition amphibious forces. The general exploded, however, when he learned of the action, because he feared the international community would condemn the United States for polluting the gulf. It did not happen, since it was clear that Saddam Hussein gained much more of the world’s opprobrium with his destruction of Kuwait’s oil wells and pollution of the surrounding environment.

Throughout the war, on a host of issues, Schwarzkopf and Arthur maintained a good working relationship. Indeed, the general considered Arthur a true leader and “one of the most aggressive admirals I’d ever met.”6

Arthur’s Maritime Campaign

Arthur’s signal achievement in the direction of U.S. and allied naval forces was to convince Saddam that he intended to unleash the U.S. Marine Corps on him and carry out another “Inchon” amphibious assault that would destroy Iraqi forces in Kuwait and end the war. Arthur’s first step was to clear enemy forces from the northern gulf, and that effort truly reflected the joint-service and multinational aspect of Desert Storm.

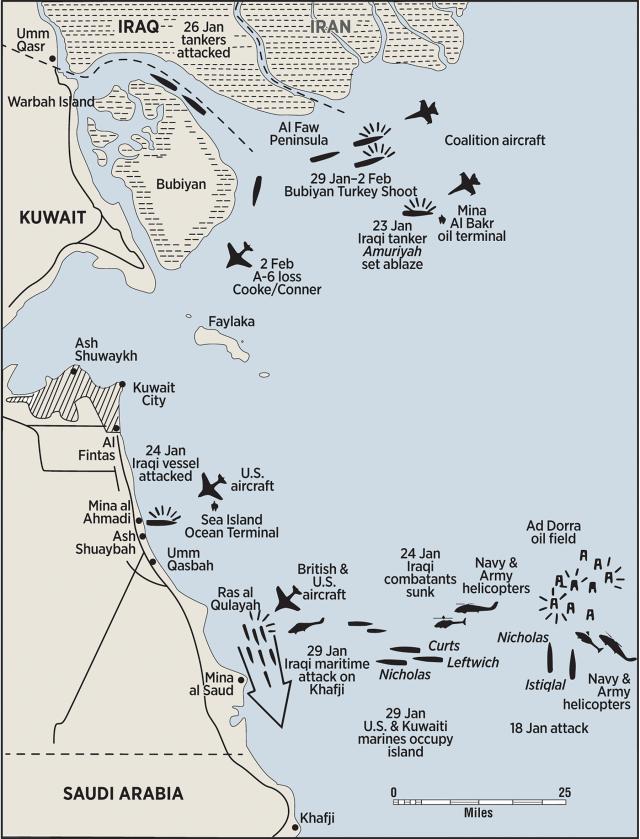

Employing innovative hunter/killer tactics, advanced radars, night-vision gear, and Sea Skua and Hellfire missiles, teams of U.S. Navy, U.S. Army, and British helicopters sank a number of Iraqi combat vessels.

The guided-missile frigate USS Nicholas (FFG-47) and Kuwaiti missile boat Istiqlal captured the war’s first enemy troops when they seized an Iraqi-fortified platform in the gulf. On 24 January, Navy SEALs and Army helicopter teams operating from the guided-missile frigates Nicholas and Curts (FFG-38) and destroyer Leftwich (DD-984) seized 75 more Iraqis on or near Qaruh Island. Finally, in the so-called “Bubiyan Turkey Shoot,” U.S., British, and Canadian planes sank or disabled 20 Iraqi naval vessels attempting to flee to Iran for sanctuary.

Hence, in a few short weeks in January, coalition naval forces gained control of the northern gulf and sank or forced into Iranian hands more than 140 Iraqi Navy vessels, including every one of the 13 especially dangerous missile-launching craft.

Arthur then moved his fleet closer to Kuwait and ordered the carriers to intensify attacks on military targets along the enemy-held coast. U.S. and British mine-countermeasures forces cleared lanes through suspected minefields, later confirmed to consist of 1,200 old but also technologically advanced weapons. From positions close offshore, the battleships could identify and then, with their powerful 16-inch naval rifles, precisely bombard hunkered-down enemy forces. The ships’ thick armored hulls and their escort, the British destroyer HMS Gloucester (which downed an incoming Iraqi Silkworm with a surface-to-air missile), enabled the battleships to carry out their mission. The other ships of the fleet lacked the battleships’ heavily armored hulls, which put them in great jeopardy.

During Desert Shield, Schwarzkopf had forbidden Arthur from sending aircraft over these waters to map the minefields for fear of triggering the war before the coalition was ready. As a result, the amphibious assault ship Tripoli (LPH-10) and shortly afterward the guided-missile cruiser Princeton (CG-59) detonated mines that severely damaged and could have sunk these ships save for the Herculean efforts of their damage-control teams.

The minefields did not dissuade Schwarzkopf or Arthur from launching an amphibious invasion of Kuwait. They had ruled out that action as unnecessary by 2 February, fearing the devastation to Kuwait’s coastal infrastructure and potentially heavy casualties to the assaulting Marines and amphibious ships.

The Navy’s actions in the northern gulf, however, did reinforce Saddam Hussein’s belief that the coalition was about to launch such an assault. By mid-February, Arthur had deployed 31 ships of the Amphibious Task Force, with the 4th and 5th Marine Expeditionary Brigades and the 13th Marine Expeditionary Unit embarked, just off Kuwait’s shores. At the same time, carrier aircraft and the battleships poured a deluge of fire onto coastal targets and the enemy-occupied island of Faylaka, and SEALs carried out daring and attention-getting operations on the coast.

The strategic ruse worked perfectly. Those Iraqi combat divisions, hundreds of artillery pieces, and five antiship missile batteries positioned along the shore were not able to swing against the coalition’s massive and powerful U.S. and allied ground army, including General Boomer’s I Marine Expeditionary Force, that emerged from the desert to flank Saddam’s army and liberate Kuwait.

The coalition’s unrelenting air and sea assault on Iraq and the masterful ground campaign kicked off on 24 February brought Saddam to his knees only 100 hours later. Many observers believed the dictator would no longer threaten regional peace or continue to terrorize his own citizens. As demonstrated by the outbreak of another war with Iraq in 2003, however, that assumption proved false.

The Navy fought the Persian Gulf War as part of a joint-service and multinational coalition that accomplished one of the most successful campaigns in military history. Following the dictates of U.N. resolutions and U.S. strategy, the Navy and the other components of the allied coalition liberated Kuwait and limited Saddam’s ability to threaten his neighbors. The Navy and its military partners reduced the Iraqi Air Force by more than half, severely constrained the Iraqi Navy’s combat capability, destroyed 4,200 tanks, armored personnel carriers, and artillery pieces, and killed, wounded, or captured 100,000 enemy troops. The Navy accomplished its mission without the loss of a single ship. The enemy shot down six Navy planes, killing six naval aircrewmen, including Lieutenant Commander Michael S. Speicher, whose remains were not identified until 2009. (Subsequently, he was promoted to commander and then captain.) The Marine Corps suffered the loss of seven aircraft and the killing or wounding of 110 Marines, mostly during ground combat.

After the Storm, a New Direction

The U.S. Navy learned from Desert Storm by improving its ability to contribute to multinational and joint-service operations against enemies afloat and ashore. U.S. Naval Forces CENTCOM (NAVCENT) also gained significant operational experience after the war working on the international effort to restore Kuwait’s infrastructure, clear the gulf of mines, maintain the maritime patrol against Iraq, and deter Saddam’s newly aggressive activities.

The Navy’s maintenance of “no-fly” zones over Iraq, launch of Tomahawk strikes against military targets in and around Baghdad during 1993, and fleet movements in 1994 moderated the dictator’s behavior, if only temporarily. The Navy worked in the postwar period to assure the friendly nations in the gulf region of U.S. constancy through multinational exercises and training missions.

The naval service took steps to improve its capability in the region and its contribution to CENTCOM. In 1992 and 1993, the Navy agreed to the establishment of Commander NAVCENT as a permanent billet headed by a three-star admiral and the maintenance ashore in Bahrain of his headquarters. Vice Admiral John Scott Redd, who led NAVCENT during 1994, later stated the obvious when he remarked that “if it looks like a fleet, acts like a fleet, and operates like a fleet, it’s a fleet!”7 Finally, on 1 July 1995, the Navy agreed and stood up the U.S. Fifth Fleet as CENTCOM’s dedicated naval combat force.

The Navy also worked to incorporate the lessons of Desert Storm in joint-service operations. The fleet improved many of its communications and data-link systems, its adaptation to the air tasking order, the development of common missiles and other ordnance, and the equipping of its helicopters with better weapons and targeting devices, as well as significantly upgrading its mine-hunting ships and aircraft.

At the strategic level, the Persian Gulf War inspired the Navy to strengthen its evolution from the global Cold War to a new era of regional conflict in which non-Soviet nations and navies likely would be the adversaries. The Navy’s 1992 white paper From the Sea announced this new strategic approach; it was refined two years later with Forward . . . From the Sea. Both guiding documents incorporated the experience of the Gulf War. They called for the employment of sea-based “power projection” forces to influence multinational and joint-service campaigns ashore. Hence, the Persian Gulf War truly marked a milestone in the modern history of the U.S. Navy.

1. John LaPlante interview with Marolda and Schneller, tape 3, side 2, in Edward J. Marolda and Robert J. Schneller Jr., Shield and Sword: The United States Navy and the Persian Gulf War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001), 31.

2. John F. Lehman Jr., Command of the Seas (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1988), 395.

3. IMEFB, 19 March 1991, as related in Shield and Sword, 273.

4. Stanley R. Arthur interview with Marolda in The Oral History of Adm. Stanley R. Arthur, USN (Ret.) (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 2016), 515.

5. Letter, ADM Henry H. Mauz Jr., USN (Ret.) to Marolda, 12 June 1996, as related in Shield and Sword, 114.

6. Gen H. Norman Schwarzkopf Jr., USA (Ret.), It Doesn’t Take a Hero (New York: Bantam Books, 1992), 437.

7. Quoted in Jeffrey H. Thomas, “The Fifth Fleet Stands Again,” in Pull Together (publication of the Naval Historical Foundation), Spring/Summer 1997, 9.