Throughout the centuries many ships have had mascots – cats, dogs, monkeys, parrots – and during World War II there was a profusion of them. Many were adopted as part of the ship’s crew, but none ever achieved Sinbad’s stature or lasting fame. His fame extended to sailors of all countries whose ships plied the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea and spread ashore to U.S. cities far inland.

It all started on a winter’s evening in late 1937, when Blackie and his friend Ed Maillard returned from liberty to the USCGC Campbell (WPG-32) in Staten Island, New York. Blackie was carrying a small gym bag. Quietly, the two men made their way down to the berthing area, trying not to attract attention, because the bag held a husky black and tan mutt with white eyebrows. The next morning, barking alerted the other men to what Blackie had brought on board. Named “Sinbad” by the Campbell’s salty crew, he quickly became one of them.

His first years were without major disruptions, until the Campbell was dispatched to conduct surveys around Greenland in summer 1940. While on liberty ashore, Sinbad discovered chasing sheep was great sport. However, some of the sheep lost strength and died, while others were so nervous they would not eat. The whole countryside was roused. Vowing to eliminate this lone terror, they tracked it to the Campbell.

The evidence was clear, and the ultimate penalty was demanded. However, the Campbell’s commanding officer, Captain Joe Greenspun, would not agree, for no man could condemn a dog for simply being a dog. But he knew that if the attacks continued Sinbad would be killed and the crew would declare war on the locals. So, as with any member of the Coast Guard charged with a crime, a court-martial was held, with the executive officer as Sinbad's defense counsel. The evidence was clear, and Sinbad was found guilty of "conduct unbecoming a member of Campbell crew." He was busted from First Class Dog to Seaman Pup and banned from ever going ashore in Greenland. This was the first of his two courts-martial. His second was years later when he went AWOL in New York.

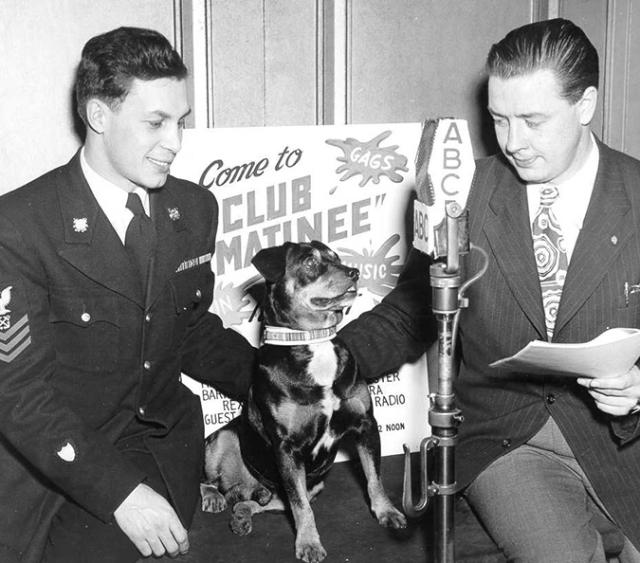

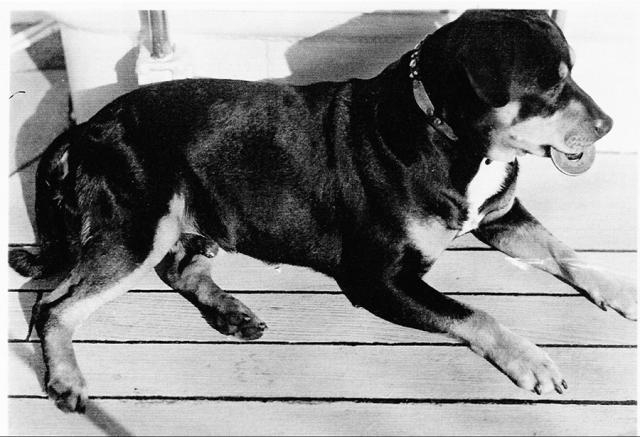

His adventures continued and along with them a growing fame. Sinbad accompanied the Shore Patrol to the bordellos in Portugal. In North Africa he was the guest at a sultan’s palace. He stopped traffic when he came to Boston and New York, and in Ireland, the Belfast newspaper ran a notice whenever Sinbad was in port. There was a Reader’s Digest article in addition to photos and stories in national weekly magazines. In December 1943, Martin Sheridan of the Boston Daily Globe described Sinbad as “rough tough and rowdy,” a combination of “liberty-rum-chow hound with a bit of bulldog, Doberman pinscher and whatnot – mostly whatnot.” Actually, Sinbad was not that big, just 40 pounds of sea dog with an attitude.

He even appeared in news reels.

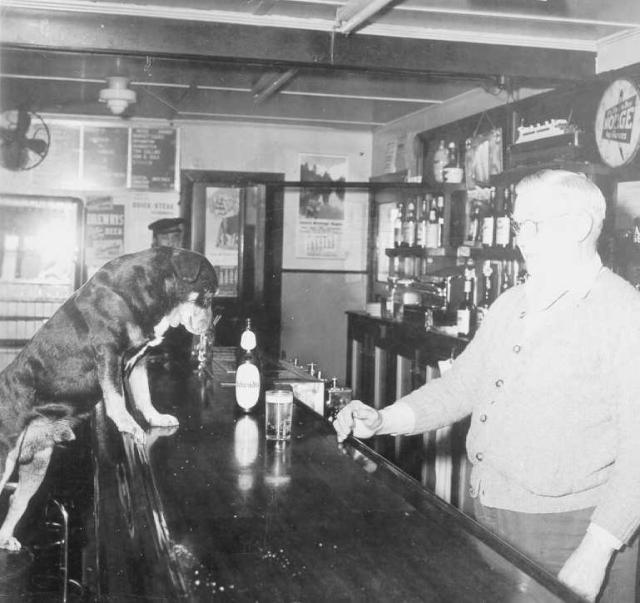

Sheridan touched briefly on Sinbad’s drinking habits. He liked boilermakers and draft beer. He was known in every bar and saloon from the New York docks to Boston’s Sculley Square. The only complaint his shipmates had was that he never paid for drinks when ashore. When he was done drinking, he’d wait by the curb for a taxi to take him back to the cutter. The men kept a can of money in the Quarterdeck Shack to pay for his cab fare. He also knew which bus to take to the beer garden at the Argentia Naval Base. One time in upper Manhattan a woman reported to the police there was dead dog in the gutter. Arriving on scene, the police recognized Sinbad was not dead, but rather dead drunk, and took him back to the Campbell.

Sinbad was as important to the ship as its engines and guns. With their four-legged shipmate as a morale builder, the crew never lacked for entertainment. Al Vetter recalls that Sinbad had a personality all his own and was a good luck charm during World War II. His favorite trick was balancing a metal washer on his nose then flipping it in the air and catching it in his mouth. One not so funny incident was when Sinbad pulled the lanyard that fired a 300-pound depth charge off the side of the ship and almost blew the Campbell out of the water.

In March 1943, when the Campbell was rammed by U-606 and had to be towed back to port, most of the crew was transferred to another ship, but the commanding officer, Commander Jimmy Hirshfield, kept Sinbad on board as an “essential” member of the crew. The men believed nothing bad could happen as long as Sinbad was there. And nothing bad did happen; they were all reunited a few days later in St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Sinbad was so much a part of the Campbell that when the famous naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison had a coat of arms designed for the ship, Sinbad was placed on top.

After he retired from the Coast Guard on 21 September 1948, Sinbad lived at Barnegat Coast Guard Station in New Jersey until his death on 30 December 1951. He was honored with a full military funeral and placed to rest at the foot of the flag pole, his grave marked by a bronze plaque.

The Campbell was decommissioned on 1 April 1982, but Sinbad’s memory lives on. When the Coast Guard built a new cutter named Campbell, Norm Rabkin, Dave Blum, and others from the original Campbell crew offered the commanding officer, Commander D. Brian Peterman, a statue of Sinbad. He accepted without hesitation, and the crew built a special place for it on the mess deck. It sits there to this day, a good luck symbol for the ship. The crew took Sinbad’s memory a step further, painting paw prints on the main deck, stenciling “SINBAD” on the stern of the ship’s motor surfboat, and flying a large “Sinbad Lives” flag while under way.

Eddie Lloyd, the editor of the old Coast Guard magazine, said: “Sinbad was a salty sailor, but he’s not a good sailor. He'll never rate gold hash marks nor good conduct medals. He’s been on report several times, and he’s raised hell in a number of ports. On a few occasions, he has embarrassed the United States government by creating disturbances in foreign zones. Perhaps that's why Coast Guardsmen love Sinbad; he’s as bad as the worst and as good as the best of us.”

Battles, hurricanes, and the rigors of life at sea never dulled his preference for being at sea. He loved to stand on the heaving deck of the cutter with the spray breaking over his wiry body. Sinbad was the quintessential salty dog. He served for 11 years on board the Campbell, earned five Battle Stars during World War II, had a book written about him, starred in a movie short, and earned a place in history. Loved by thousands, he never let fame go to his head but remained just one of the crew.

Mine is a story that cries to be told of men gone before.

Of time that is now grown old.

So listen now softly as I speak to you

With turn of my shaft, with beats of my screw.

For how many skippers

How many brave men

Having fit out the Campbell

Steamed seaward again?

With heart that is ship, with soul that is crew

I’ve plied many oceans, stormy gray and calm blue.

On my decks old Sinbad was created to fame.

In my hull lived men now part of my name.

Author Unknown