To most civilians, the pervasive use of acronyms, initialisms, and jargon in the U.S. Navy may seem like an impenetrable secret language. Although many naval words and phrases have managed to drift into common English usage—including “windfall,” “figurehead,” and “listless”—there are many more terms that are rarely understood by anyone other than sailors.

When two people who had served in the Navy meet for the first time, they may drop a few words into the conversation to establish their maritime bona fides. They may joke about “airdales” and “bubbleheads” while mentioning a fondness for “mid-rats” and “gedunk.”

To a U.S. Navy sailor, gedunk is junk food—originally ice cream but expanded to include candy, soda, potato chips, etc. “The gedunk” is the snack bar on a ship where said junk food can be purchased. Proceeds from gedunk sales usually are used to fund services, activities, and emergency loans for the crew.

Gedunk (GHEE-dunk) is very odd word. It appears vaguely Asian or perhaps German or Dutch. It even seems nonsensical, like a word taken from Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky” or any number of Dr. Seuss books.

Theories abound concerning the word’s origin. Some word sleuths think it stems from the Chinese for “a place of idleness” and was picked up by sailors and Marines on the Yangtze Patrol in the 1920s. Others think it was adapted from a German term for dipping bread to sop up coffee or gravy. Another theory of foreign origin points to the Anglo-Indian word “godown” which means “a place where goods are kept.” Some amateur etymologists believe that gedunk is an onomatopoeia for either the sound made by vending machines when dispensing candy or the sound of a scoop of ice cream being dropped into a bowl. Yet others think it derives from shipping crates that had “G.D.” stenciled on them when they contained “general dairy” products such as ice cream.

However, the word and its association with ice cream almost certainly originated in the pages of the Chicago Tribune. Gedunk first gained wide notice in the long running column “A Line O’ Type or Two” (the title being a pun on the Linotype machine used in printing). The column featured quips, witticisms, and poems that were often written in eye dialect and pronunciation spellings to imply that the contributor had an accent. Starting in January 1925, the column featured a series of submissions debating the etiquette of dipping cakes into coffee, which in faux German was referred to as “gedunking.”

After a week of contributors humorously commenting on the act of gedunking, a reader thought it was necessary to give a lesson on the actual German word for dipping food in liquid: “The verb is tunken or eintunken; the past participle is eingetunkt and the noun is tunker. But your benighted contribs use one word for all three meanings, and that word is spelled wrong!” Not considered at the time was that “gedunk” probably was a play on “dunke” which had existed in the Pennsylvania German dialect since the mid-19th century.

Another reader submitted a poem about how the act of dipping food in a beverage that Germans were trying to introduce under “the new term gedunking” originated with Vikings as “dopping.” The poet argued that credit for the custom should be given to Swedes.

Working at the Tribune at this time was cartoonist Carl “Swede” Ed (it rhymes). Ed was the creator of the immensely popular comic strip “Harold Teen.” Launched in 1919, the strip had tapped into a new and growing subculture—teenagers. Prior to the 20th century, there were only adults and children. As American society became more affluent, an increasing portion of the maturing population stayed in school rather than immediately joining the work force. This, combined with the preponderance of cars, spawned a population of young adults who had an unprecedented amount of independence. Booth Tarkington had found success writing about the new teenage phenomenon in his novel Seventeen, so Ed thought a similarly themed comic strip would find an audience.

Ed’s editors were at first skeptical but “Harold Teen” did indeed prove to have captured the zeitgeist of post-WWI American youth culture. At its peak, “Harold Teen” appeared in more than 800 newspapers and was followed by 35,000,000 readers. Through the strip, Ed both reflected and dictated teenage fashion of the time. Much to the chagrin of teachers and parents, he also had an impact on the language of teens by popularizing many slang words and catchphrases—and the most far-reaching was his use of “gedunk.”

In a 1944 interview, Ed recounted that years earlier he and a colleague were sitting in his kitchen making jokes when the word “gedunk” came up. Ed thought it was an interesting word and wanted to work it into his strip.

One year after being bandied about in the “Line O’ Type or Two” column, gedunk made its “Harold Teen” debut. In a January 1926 strip, Harold (wearing a trendy raccoon coat) walks to his favorite hangout, the Sugar Bowl, where the soda fountain’s proprietor Pop Jenks has started advertising his new “Gedunk Sundae.” Initially, Ed did not describe the sundae, but so many readers began to request the recipe that he explained it was a glass of chocolate with two scoops of ice cream in which lady fingers were “gedunked.”

The gedunk sundae became an important fixture of the strip and quickly developed into a national fad. Supermarkets began to advertise all the ingredients needed to make gedunk sundaes at home. At the local Piggly Wiggly, shoppers could find Gedunk Sundae candy bars along with Baby Ruths, Milky Ways, and Oh Henrys for the bargain price of two for a nickel. Companies sponsored gedunk social parties for their employees. Ice cream parlors throughout the country began to offer gedunk sundaes and soon became so associated with the frozen treat that “see you at the gedunk” became a common phrase. Numerous recreational sports teams adopted the name Gedunkers (and “dunking” would later become a common term in basketball).

Programs for variety shows often included a comedy sketch set in a soda fountain titled “The Gedunk.” In one such show, the “Gedunk” sketch shared billing with Joe Mendi, a performing chimpanzee that gained fame by being an exhibit in the Scopes Monkey Trial.

In 1928, the silent film Harold Teen starring Arthur Lake prominently featured the by-now famous ice cream treat. Lake enjoyed making the film so much that with Ed’s permission he opened his own Sugar Bowl soda fountain in Hollywood, where he was known to hang out and serve sundaes. He also was frequently spotted cavorting with pals on his motorboat Gedunk Sundae. Another comic strip character would bring Lake even greater fame when he portrayed Dagwood Bumstead in the “Blondie” movie series.

A line of Harold Teen merchandise, a second movie starring dancer Hal Le Roy, and a daily WGN radio show further established the character’s prominence in the era’s pop culture landscape.

When the gedunk craze was at its peak, the U.S. Navy was working to improve the quality of life on its ships. By 1930, the Navy had awarded a lucrative contract to RCA to install audio equipment so that sailors could enjoy “talkies” at sea. The Navy also started adding a new feature on ships—soda fountains.

Ice cream makers had been on U.S. Navy ships since the early 1900s, but they became even more important in 1914 when Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels issued General Order 99, which prohibited alcohol on all naval vessels. The Navy found that sailors seemed the think that having a large selection of ice cream was a fair replacement for booze. In January 1930, the USS Memphis (CL-13) deployed with a brand-new soda fountain that cost $7,000 ($110,000 in 2020 dollars). The USS Pennsylvania (BB-38), flagship of the Atlantic fleet, had a soda fountain designed to look like a typical neighborhood ice cream parlor with tiled walls that featured images of famous ships.

Soda fountains soon became so common on ships that Our Navy magazine drolly proposed that the new recruiting slogan should be “Join the Navy and get your sodas.” It also led to a lot of old salts complaining that the Navy had become too soft because not only were young sailors getting ice cream and laundry service, they were wearing shoes on deck.

On 1 December 1930, the Huntsville Times published a letter from a local man who described what life was like serving on board the USS Sacramento (PG-19), based in Guantanamo Bay. The young sailor wrote: “For diversion during the week we have had motion pictures in our big open-air theatre on the top deck every night and the gedunk parlor throws open its doors occasionally to serve cold tonics and frozen refreshments.” This is the first known time that gedunk appears in print when referring to ice cream and the soda fountain on a U.S. Navy ship.

Gedunk would rapidly become a term used throughout the fleet. During World War II, newspapers began noting the emergence of odd Navy terms, including gedunk for ice cream and “pogie bait” for candy (the origin of pogie bait, which has survived in the vernacular of some Marines, has a decidedly less innocent story than that of gedunk).

Even when much of the globe was suffering wartime food shortages and subjected to strict rationing, the Navy made sure its sailors had access to plenty of gedunk. Ice cream was seen as essential for morale as well as a source for calories to maintain a crew’s high level of energy. It also helped cool down sailors in the heat of battle (some sailors also discovered that sleeping in the gedunk stand was a way to escape the hotter compartments of the ship). There was even a refrigerated barge operating in the Pacific that was dedicated to making gedunk and then supplying it to ships that were too small to have their own ice cream makers.

Because gedunk was so important for keeping up the spirits of the crew, some ships reserved it for enlisted sailors when supplies were low. Officers had to do without. On other ships, officers were known to pull rank to cut in line and get their gedunk before the stand closed—which did not endear them to the crew. There is an anecdote about two officers who tried this stunt only to hear someone bark at them to wait their turn. When they looked to see who had dared to rebuke them, they spotted Admiral Bull Halsey waiting in line with the rest of the sailors.

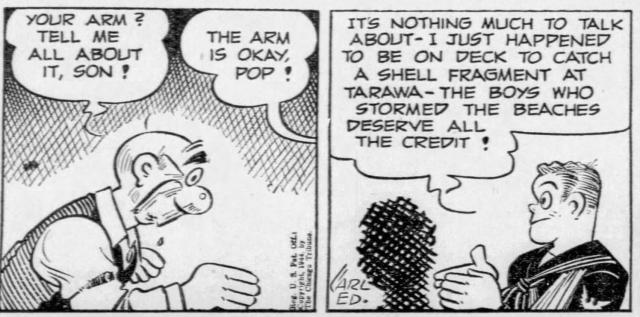

In the comic strip, Harold Teen did his part for the war effort by enlisting in the Navy and would later be wounded during the Battle of Tarawa when his ship was sunk. Oddly, there was no mention of gedunk until he returned home and once again was able to enjoy sundaes with Pop at the Sugar Bowl.

The popularity of “Harold Teen” began to wane as Ed grew older and more out of touch with ever-evolving youth culture. He retired in 1959 and died two weeks later. His family decided not to continue the strip. Harold and his beloved gedunk sundaes quickly faded from memory. Within four years of Ed’s death and the end of the strip, the editors of All Hands magazine were unable to definitively answer a reader’s question about why ice cream was known as gedunk in the Navy.

Today’s audience probably could not pick Harold Teen out of a lineup consisting of Lil’ Abner, Smokey Stover, Smitty, and Joe Palooka. And despite at one time being at the center of a national craze, the word gedunk has become almost unique to the Navy—though it occasionally pops up in surprising places. Grove City College in Pennsylvania still has a snack bar named Gedunk that was named by Navy veteran returning from the Korean war.

The meaning of gedunk in the Navy has been expanded to include junk and the storeroom where random equipment is kept. It is also used for things deemed as worthless, such as gedunk medals (awards that everyone gets) and gedunk sailors (new recruits). Some sailors have been known to quietly mutter about gedunk admirals.

The gedunk on Navy ships still exists but has evolved from a simple soda fountain into a convenience store with a wide range of products. Sailors can still get it their ice cream, but it is now often dispensed by a machine affectionately known as the “auto-dog.”

The strange history of “gedunk” connects the Amish, comics, ice cream, the Navy, junk, and basketball. To recap: Gedunk began as an imitation Pennsylvania German word meaning “to dip.” Because of the comic “Harold Teen,” gedunk then became associated with a sundae in which lady fingers were dipped into a glass of ice cream and chocolate. The resulting fad resulted in ice cream parlors becoming known as gedunks. Not long after, gedunk was used by sailors to describe the dishes of ice cream available at their ships’ soda fountains, which in turn also became known as gedunks. The term was then applied to all the junk food items for sale at a ship’s gedunk. It has since been applied to junk in general. At one point, the word branched into basketball.

According to food industry lore, a young naval officer who managed the canteen in the New Hebrides during World War II did some finagling to trade a jeep for an aircraft carrier’s ice cream freezer. He then began to experiment with tropical flavors and later used the recipes to start a business with his brother-in-law. Naming their ice cream company after themselves, Burt Baskin and Irv Robbins would become quite successful.