As with so many things in the Navy, there are special customs relating to the American flag. To begin with, when flown on board a Navy ship, it is properly referred to as the national ensign. The procedures for displaying the national ensign on board ships differ, depending on the circumstances.

At Sea

When far out at sea, with no one to see it, the ensign normally is not flown to limit the wear and tear flags suffer from wind and inclement weather. The ensign is flown at sea when:

- Getting under way and returning to port

- Joining up with other ships

- Cruising near land or in areas of high traffic

- Engaged in battle.

When displayed under way, the ensign is flown from the gaff (an angled spar, usually located on the after side of the mainmast).

In Port

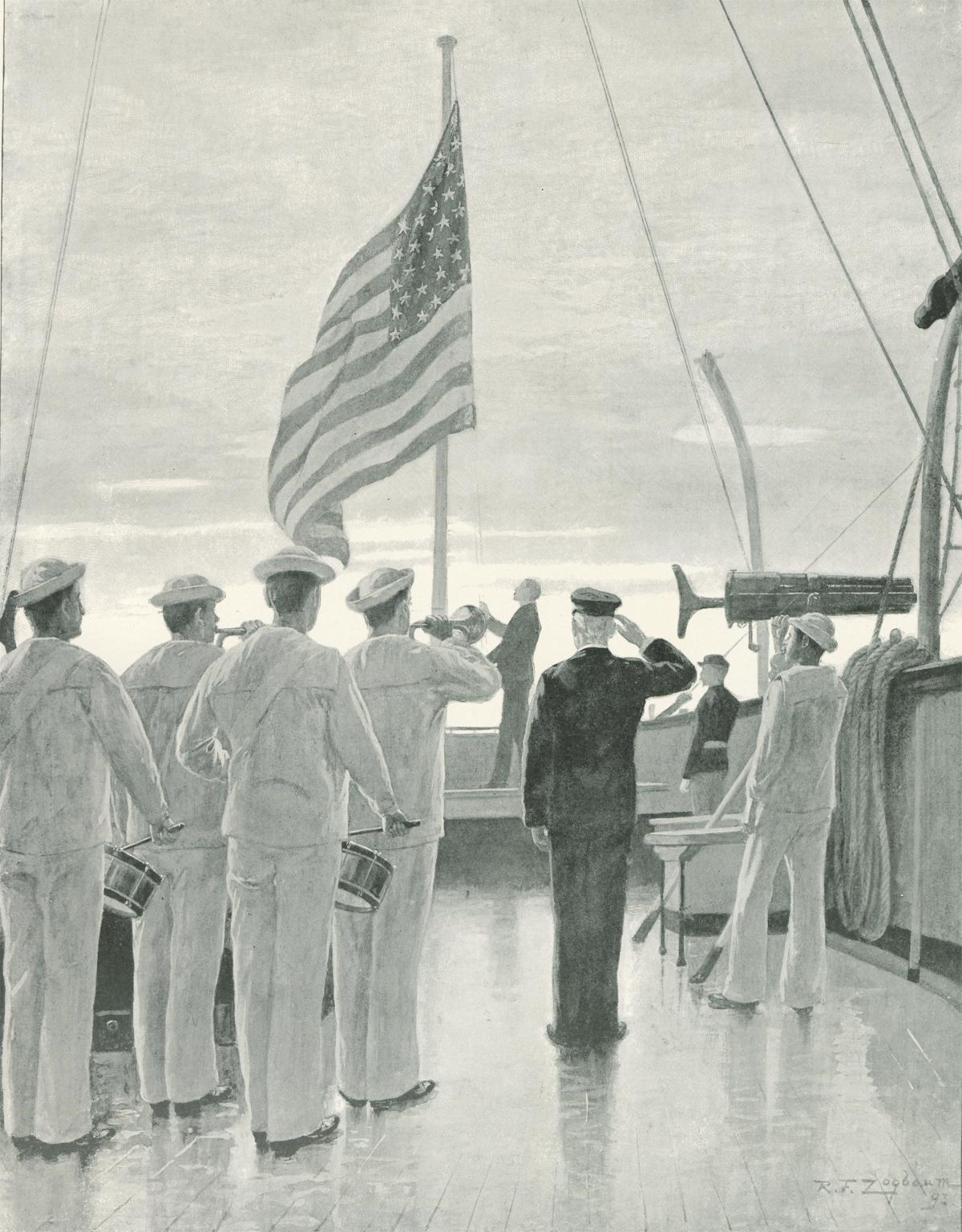

When ships are in port, whether moored to a pier or anchored offshore, they observe the formal ceremonies of morning and evening colors, with the ensign being flown from the flagstaff (a spar mounted at the stern).

If more than one Navy ship is in port, the one with the most senior officer (SOPA, or senior officer present afloat) holds colors, and all the other ships follow her lead. This ensures that all ships hold colors simultaneously, which makes for a much more impressive ceremony than if each ship acted independently.

Whether in the morning or the evening, first call to colors is announced (over the ship’s 1MC system, or sometimes by a special bugle call) five minutes before colors to alert all hands that the ceremony is imminent. At that same time, a visual alert—a special yellow and green pennant called PREP (for preparative)—is two-blocked (hoisted all the way up) on the outboard halyard of the port yardarm.

For morning colors, at exactly 0800 the PREP pennant is dipped (brought halfway down), either a whistle or a bugle sounds “Attention,” and the national ensign is briskly hoisted, while one of several things happens, depending on the ship:

- The band plays the national anthem (if the ship or shore station has a band)

- A bugler plays “To the Colors” (if the ship or station has a bugler assigned but no band)

- A recording of the national anthem is played over the 1MC

- A recording of “To the Colors” is played over the 1MC

- Silence is observed while the colors are being hoisted (if none of the choices above are available).

All hands topside render a hand salute (unless they are in formation) and hold it until “Carry on” is sounded. Once the ceremony has ended, the PREP pennant is hauled down and all hands resume what they were doing before attention was sounded.

In the evening, the colors ceremony is much the same, except it takes place at sunset, “Retreat” is substituted for “To the Colors,” and the ensign is hauled down slowly and ceremoniously.

Half-Masting the National Ensign

As a means of honoring the death of an official or during other periods of mourning, such as after a terrorist attack, the national ensign may be lowered halfway (by decree from higher authority). Called half-masting, the procedures are as follows:

- If the ensign is already flying when word is received that it is to be half-masted, it is immediately lowered.

- In port, if the ensign is not already flying, morning colors is held as normal, with the ensign being hoisted smartly, all the way to the peak (top of the flagstaff), remaining there through the national anthem or “To the Colors,” and then lowered ceremoniously to the half-mast position.

- On Memorial Day, the national ensign is half-masted until noon, at which time a special gun salute is sounded (one gun fired every minute for 21 minutes) to honor those who have given their lives in the defense of the nation. At the conclusion of the firing, the national ensign is hoisted to the peak and flown that way for the remainder of the day. If a 21-gun salute cannot be fired, the ensign is raised to the peak at precisely 1220.

- During burial at sea, the ensign is at half-mast from the beginning of the funeral service until the body is committed to the deep.

Dipping the Ensign

A very old custom of the sea is that merchant ships “salute” naval vessels by dipping their ensigns as they pass. When a merchant ship of any nation formally recognized by the United States salutes a ship of the U.S. Navy, she lowers her national colors to half-mast. The Navy ship returns the salute by lowering her ensign to half-mast for a few seconds, then closing it back up. The merchant vessel then raises her ensign back up.

If a naval vessel is under way and not flying the ensign (as discussed above) and a passing merchant ship dips her ensign in salute, the Navy ship will hoist her colors, dip for the salute, close them up again, and then haul them down after a suitable interval.

If a naval ship is at anchor or moored to a pier and a passing merchant dips her ensign, the salute is returned by lowering the national ensign halfway down the flagstaff, pausing for a moment, then returning it to the peak.

Naval vessels dip the ensign only to answer a salute; they never salute first.