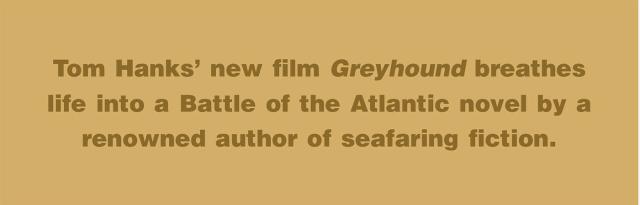

Author C. S. Forester wrote more than 40 books and is best known for his novels about the fictional Royal Navy officer Horatio Hornblower, published between 1937 and 1962. His astonishing success with those books, still among the best sea novels ever written, often overshadows the fact that he also was one of the most prolific contributors to Hollywood’s golden age, from 1932 to 1957. In fact, his skill in producing movie scripts brought him from his native Britain to the United States twice: once in the 1930s, when Hollywood was recruiting new blood, then again in 1942, in the midst of war. Eventually, Forester, whose birth name was Cecil Louis Troughton Smith, settled in Berkeley, California, and became a U.S. citizen, though he never lost his British accent.

Even as a novelist, Forester often thought and wrote as a screenwriter. As he explained the process, he would first imagine a scene in his mind’s eye, looking at it not only three-dimensionally, but in four dimensions, since he could be both inside and outside the character at the same time. It was not a lot different from imagining a movie scene. “I can run through a scene,” he wrote later, “like a Hollywood director in his chair in a projection room.”1

It is no wonder that a dozen of his novels became major motion pictures, and a list of the actors who starred in these films reads like a veritable Hollywood who’s who:

- Charles Laughton in Payment Deferred (1932)

- Robert Stack in Eagle Squadron (1942)

- Paul Muni in Commandos Strike at Dawn (1942)

- Gregory Peck in Captain Horatio Hornblower (1951)

- Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn in The African Queen (1951)

- Cary Grant in The Pride and the Passion (1957)

Now another name can be added to that list: Tom Hanks. His new film, Greyhound, for which he wrote the script and which is coming to Apple TV+ on 10 July, is adapted from Forester’s 1955 novel The Good Shepherd.

The Book and Its Protagonist

The Good Shepherd is not among the best known of Forester’s sea novels, though the Naval Institute Press republished it in 1989 as part of its Classics of Naval Literature series. The story centers on 40-something-year-old U.S. Navy Commander George Krause, who, as captain of the fictional destroyer USS Keeling, is the escort commander for a North Atlantic convoy during the height of the Battle of the Atlantic in 1943.

Rather than set his story amid a grand sea battle such as Midway or Leyte Gulf, Forester focuses instead on the more quotidian, yet absolutely essential, work of escorting Allied supply convoys safely across the North Atlantic in the face of often relentless attacks by German U-boats. Krause in this scenario is the Good Shepherd watching over his flock, especially by night. The book’s title also illuminates a key aspect of Krause’s character, for he is deeply religious.

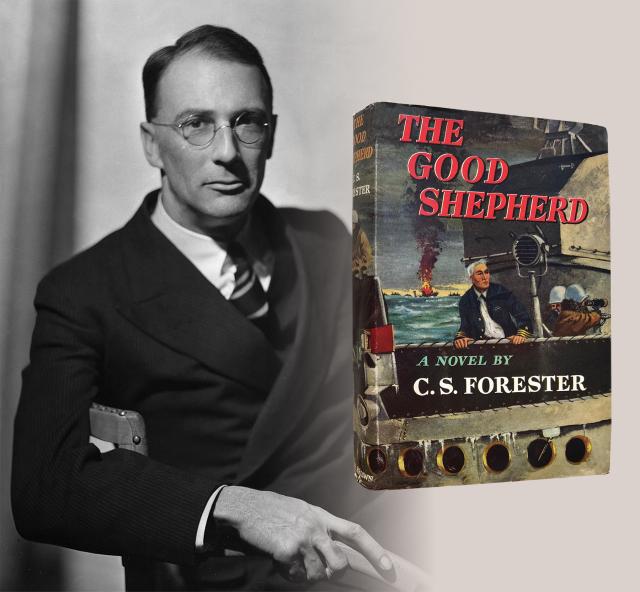

As in all his naval fiction, Forester gets the small things right. In fact, given his intimate knowledge and understanding of naval protocol and technology, readers often assume that Forester spent time as a Royal Navy officer. He did not. Rejected for service in 1940 because of a failed physical, he spent World War II as an observer, though one with an especially keen eye. He did have some sea time. He lived on a small boat in the 1930s and was a passenger on a tramp steamer from Central America back to Britain, but he gathered much of the technical background for The Good Shepherd while a guest in the Fletcher-class destroyer USS Abner Read (DD-526).

Observer on Board a Destroyer

In June 1943, Forester was acting as a propaganda agent for the British government, writing newspaper columns that promoted Anglo-American unity. The U.S. government was equally eager to have its efforts in the Pacific theater appreciated by the British public, especially in light of the fact that some Britons resented the commitment of so many U.S. resources to the war against Japan when, in their view, the war against Adolf Hitler’s Germany should take precedence. With both governments eager to influence public opinion, U.S. Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, an old newspaperman himself, wrote orders to Forester (stamped SECRET) to report aboard the Abner Read as a guest and accompany her on a cruise to Alaska.2

Like Hornblower, Forester was always seasick during his first several days at sea. He nevertheless threw himself into gaining a complete understanding of the workings of the ship. He spent a lot of time on the bridge but also climbed down into the engine spaces and of course dined in the wardroom. Forester was indefatigable in asking questions to find out all he could about daily life on board a destroyer at sea. He took lots of notes and particularly quizzed the Abner Read’s navigator, Lieutenant John D. P. Hodapp, who was his onboard host and who many years later proofread the manuscript of The Good Shepherd to check for technical errors. He eventually wrote the introduction to the Naval Institute’s edition of the book.

It was from Hodapp that Forester heard about U.S. Navy Commander George P. Hunter, Hodapp’s previous commanding officer on board the USS Farragut (DD-348), who had been prone to quoting the Bible. Hodapp’s stories of this officer, whom Forester never met, inspired the character of George Krause in The Good Shepherd.3

Forester left the Abner Read at the end of June. Just under two months later, on 19 August 1943, the destroyer struck a Japanese mine off Kiska in the Aleutians. Some 85 feet of her stern was blown off and sank into the chilly waters, with the loss of 71 hands. Had it happened two months earlier, it is not inconceivable that Forester could have been one of them, which would have meant that eight of the books in the Hornblower series never would have been written.

The forward part of the destroyer remained afloat and was towed back to Bremerton, Washington, and the Abner Read eventually returned to the war. Interestingly, the after section of the ship was discovered in July 2018. It and the men entombed inside will remain in situ as a final resting place, much like the sailors in the USS Arizona (BB-39) in Pearl Harbor.

Attention to Details

If Forester was an indefatigable researcher determined to get the details right, so is Tom Hanks. When he read The Good Shepherd and concluded it would make a stirring and thoughtful film, he worked up a screenplay draft and then traveled to Annapolis, Maryland, script in hand, to talk with naval historians. He wanted to know everything: the rank insignias, communications protocols, how officers addressed one another, how to get coffee sent up from the galley, where the captain stood on the bridge. He toured the U.S. Naval Academy and visited a yard patrol craft (YP), which Academy midshipmen use for training, to familiarize himself with bridge equipment.

Like Forester, Hanks was never a naval officer, despite having portrayed one: Jim Lovell in Apollo 13. It was only right, he joked during his visit, that having played an Academy grad, he should actually see the place from which he had supposedly graduated. Touring “the Yard” incognito (“hiding in plain sight,” as he put it), Hanks was recognized by only a few mids and tourists, though when they did spot him, he cheerfully posed for selfies. He even indulged in Annapolis’s favorite fare: crab cakes.

For the filming itself, Hanks and his production team traveled to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where the World War II destroyer USS Kidd (DD-661) is berthed on the Mississippi River as a museum ship. She is the only destroyer of that era to retain her World War II configuration and appearance. It proved difficult to film the pilothouse scenes on board the ship herself, for that space would not accommodate the actors, the director, and all the equipment. As Hanks put it, “the iron bulkheads of a destroyer” are unforgiving.

As a result, the scenes in the pilothouse, where much of the action takes place, and on the bridge were filmed in a Baton Rouge studio, though most exterior shots were filmed on board the Kidd or are computer-generated images. For Hanks and for many of the film’s other actors, it was emotional to enact a World War II drama on board a vessel that had lived through it. Hanks believed the experience “changed the lives of the cast members.”4

‘The Man Alone’

In many of his books, and his film scripts as well, Forester focuses the story not only on the action and events, but also, and mainly, on what he called “the man alone.” The first of his Hornblower novels, titled The Happy Return in Britain and Beat to Quarters in the United States, opens with Captain Horatio Hornblower in command of a Royal Navy frigate in the eastern Pacific, thousands of miles from any possible oversight. That isolation compels Hornblower to make decisions by himself—not merely technical decisions about handling the ship, but also decisions with a political and even a moral dimension. The tension in the story derives not only from what happens, but also from Hornblower’s internal debate about how to react to what happens. Though the story is full of action, the reader experiences it from the perspective of—even from inside the mind of—Hornblower.5

In much the same way, despite nearly continuous action in The Good Shepherd, the reader engages the story not as a third-party observer, but from within the mind of Commander George Krause (Ernest Krause in the film, played by Hanks). As in Beat to Quarters, the story opens on board a ship at sea—not a Royal Navy frigate this time, but the Mahan-class destroyer USS Keeling as she nears the midpoint of her mission to escort more than 30 merchant ships safely across the perilous North Atlantic, where U-boat wolf packs lie in wait.

During the war, Forester served as an observer on board the destroyer USS Abner Read, where he made friends with Lieutenant John Hodapp.

That officer, in turn, told the author stories about one of his previous commanders, Bible-quoting Commander George P. Hunter (pictured on his wedding day in 1925). Hunter, in part, was the inspiration for Forester’s character Commander Krause.

That officer, in turn, told the author stories about one of his previous commanders, Bible-quoting Commander George P. Hunter (pictured on his wedding day in 1925). Hunter, in part, was the inspiration for Forester’s character Commander Krause. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive; inset: Ancestry.com

Though he is on board a crowded warship and hardly ever both awake and alone at the same time, Krause nevertheless endures a particular kind of loneliness familiar to anyone who has had command of a ship at sea. Modern technology allows him to communicate with the ships in his immediate vicinity by short-range TBS (talk-between-ships) radio, but he cannot query his naval or political seniors back in Washington because he must maintain strict radio silence lest he give away his position to the enemy. In that respect, he is as isolated as Hornblower was in the distant Pacific. He is the man alone.

Hanks is no stranger to this kind of role. He often has been the hero in action-packed dramas—Chesley Sullenberger in Sully, Richard Phillips in Captain Phillips, Captain John H. Miller in Saving Private Ryan, and Lovell in Apollo 13, to name a few—where the chief protagonist’s character as much as the action itself becomes the center of the story. But it is in Cast Away (2000) that Hanks is truly the man alone.

In that film, he portrays Chuck Noland, who finds himself literally as well as figuratively alone on an uninhabited island in the Pacific. The only dialogue is between Hanks and a volleyball that has washed ashore, which he names Wilson. Here, it is Hanks’ ability to allow the viewer to engage with his character’s state of mind that propels the movie. While Krause is never alone in Greyhound, the mental struggle of the main character allows the viewer to participate in a particularly visceral way in the continual crises of a transatlantic convoy during wartime.

‘Flat Feeling of Exhaustion’

Perhaps ironically, Forester’s own personal writing regimen also reflected the solitary man focus. For him, the genesis of all his novels and screenplays was an idea that gradually developed and matured in his head, often for months, until he was ready to write. When that moment arrived, he sat down, not with a typewriter, but with a stack of legal pads and a fountain pen. He wrote in a small, constrained hand (unlike his sweeping imagination), beginning with the first page and continuing with few breaks all the way to the end. The writing itself usually took him about three months of focused, intense labor. Afterward, he was “drained and empty.” At these times, he later wrote, he experienced that “sick, weary, flat feeling of exhaustion.”6

That evocative phrase is suggestive of the emotion that George Krause must have felt when, with the convoy finally delivered into safe hands, he fell (in Forester’s words) “spreadeagled and face downwards on his bunk, utterly unconscious.” Whether or not Tom Hanks felt “drained and empty” after he finished writing the screenplay and producing and starring in Greyhound, it is almost impossible to imagine this formidable talent “on his bunk, utterly unconscious.” He probably already was at work on his next project.7

1. C. S. Forester, The Hornblower Companion (New York: Pinnacle Books, 1964), 101.

2. J. D. P. Hodapp Jr., Introduction to C. S. Forester, The Good Shepherd (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989), viii–ix.

3. Hodapp, Introduction, xi–xii.

4. Hanks to the author, 25 April and 13 August 2018.

5. Forester, The Hornblower Companion, 107.

6. Forester, 100.

7. Forester, The Good Shepherd, 256.