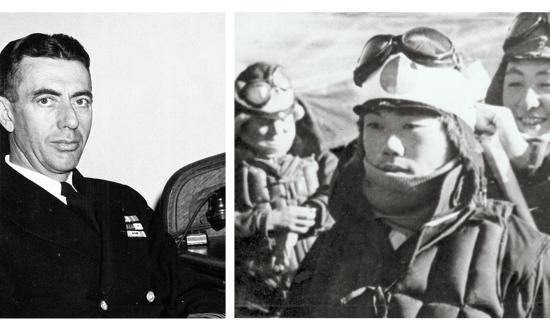

The Fletcher-class destroyer USS Franks (DD-554) participated in the Central Pacific campaign, the Battle of Leyte Gulf, and the final conquest of Japan. On the bridge of the Franks throughout her entire wartime service was Quartermaster Mike Bak. Just as the Franks was representative of the swift and fondly remembered Fletcher class, Bak was representative of the hundreds of thousands of young men who grew up during the Depression and then went off to fight in a global war. In this excerpt from his U.S. Naval Institute oral history, Bak offers a vivid first look at war-torn Japan in the immediate aftermath of its surrender in 1945.

On 14 August, an aircraft carrier launched strikes over Tokyo, and Admiral [William F.] Halsey, on board the USS Missouri [BB-63], notified Task Force 38 he had received an urgent message from Commander in Chief Pacific ordering all air operations to cease. Emperor Hirohito had promised to surrender. That was on the 14th. On the 15th, he actually did surrender.

On the 16th, the first troops started to arrive, I believe, in Japan. On 23 August, we arrived outside of Sagami Wan with the aircraft carriers to maintain surveillance over Tokyo and eastern Honshu. The major units of the Third Fleet entered Sagami Wan and anchored in selected berths. On 27 August, the minesweepers started to sweep the entrance to Tokyo Bay.

Later, when going ashore, the first memory I have was that we tied up at the Japanese naval base at Yokosuka. We tied up, and then we had to walk down this long pier toward the naval base. There were a bunch of young Japanese kids, boys and girls, looking for handouts, putting their hands out. They couldn’t talk in English, just looking for something that we could give them. Then a short distance behind them, maybe 50–100 yards away, were the parents of these kids. We would walk down. None of us who were going on liberty had any guns on us, because we were not allowed to carry guns in peacetime.

I went with a fellow crew member by the name of Eugene Reardon. A professional wrestler, he was known as “Gentleman Gene.” He was from Kansas City. (In fact, I bumped into him at a reunion that we had in San Diego.) He and I left the naval base and we walked around the area of Yokosuka, not knowing where to go or what to do. We saw an Army truck come by, and we hitched a ride. They were going to West Tokyo, so we jumped in and sat on the back of the Army flatbed truck that was covered with a tarpaulin, had no sides to it, and under the tarpaulin we found out later it was black-market goods that they were taking somewhere in West Tokyo to sell. We sat on this truck and got a ride all the way in. We spent several hours with the Army guys; they took us around and gave us a nice tour.

Then they stopped in West Tokyo, and they started selling black-market goods to the Japanese. Mostly foodstuffs. They would get yen in exchange. We were helping them sell, because we were so appreciative of the ride.

Then when it came time to go back, they gave us instructions on how to get back by train. There was a train going from Tokyo to Yokohama to Yokosuka. I’d never seen a train so jammed in my life before. They were hanging on the sides and all over.

While we roamed around West Tokyo and Tokyo, there were periods of time we saw nobody but Japanese people. There was just two of us. We kind of looked back later on and said, “Hey, we were kind of stupid to be there by ourselves and roaming around.”

The only conversation I had with any Japanese, I met some fellow who came up to me, an elderly Japanese gentleman, who spoke very good English. He said, “Hello. How are you?”

I said, “Fine. How are you?” We sat down and we talked. We talked about five or ten minutes, just shot the breeze about the war and being glad it was over; he was glad it was over. He seemed to want to talk about how happy he was that nobody was going to get hurt anymore. Just had a nice visit with him.

I had liberty several times in Japan. When I went to Tokyo, the biggest thing I remember—I wrote an article that appeared in the hometown paper later on—was the fact that it was just desolate, and bombed out. We saw nothing but ruins, and how people lived in that ruin is beyond me. Why didn’t they end the war a lot sooner? Because all the buildings seemed to be down, and a lot of people were scavenging through the ruins to pick up whatever they could, whether it was tin for new homes or whatever. A lot of poverty. It was kind of a neat thing to visit a foreign land, but on the other hand, it was just depressing to see what the ruins were as a result of the war.

The Japanese people were polite, and every time we walked down the street, they would just keep to one side of us and point. I just remember vividly them pointing at probably my rating of three stripes. We just kept waving at everybody and smiling and trying to be as friendly as we possibly could, to give them the feeling that we weren’t there to hurt them, and hopefully they wouldn’t hurt us.