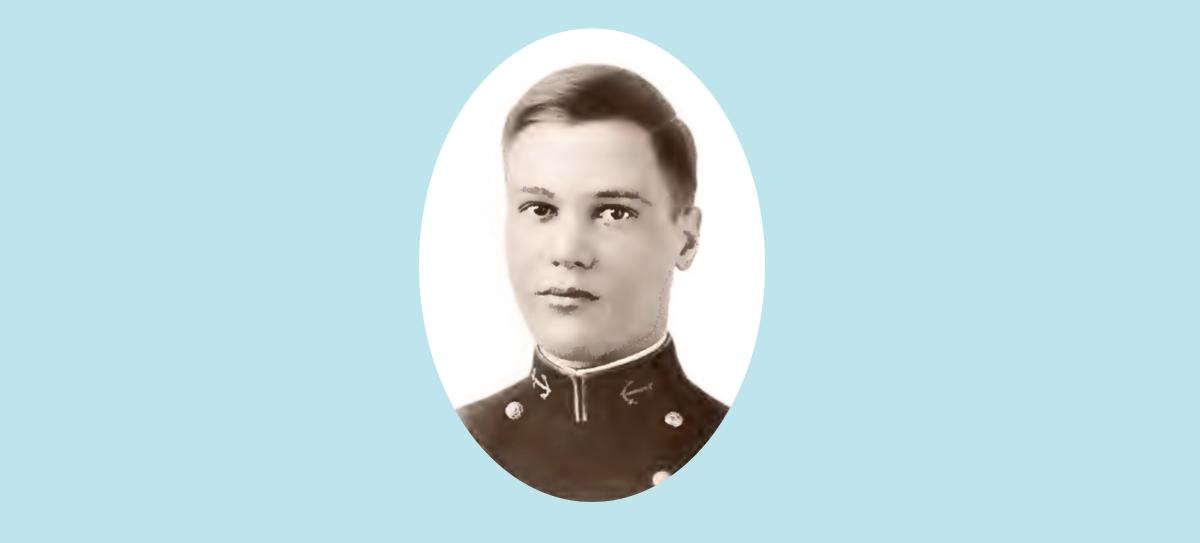

On 18 September 1987, Paul Stillwell interviewed Captain Tomlinson when he was in Annapolis for the 70th anniversary of the graduation of the U.S. Naval Academy class of 1918. Tomlinson and his classmates left Annapolis a year early because of World War I. He went on to a distinguished career in aviation. This is an edited excerpt of their interview.

Being a midshipman at the Naval Academy was an escape from problems in high school in New York State. The board of education thought I’d be better off somewhere else, so my family obtained an appointment for me to the Naval Academy. During summer 1914, the only entrance to Bancroft Hall the plebes were allowed to use was the main entrance. The ones at the ends of the original wings were always kept locked. To cut down on foot travel, I studied the construction of Bancroft Hall and decided that with the crevices between the stone blocks, I could slip along with my feet on the level with the bottom of the window sill. There was a similar device for handholds up above.

But one morning we went to the rifle range after it had been raining all night. When we came back, I walked across the corner of old Farragut Field and got the soles of my shoes wet. When I got about halfway across this ledge to my room, one foot slipped, and I wound up in the moat, with my left leg broken in three places. As a result, I spent most of plebe summer in the naval hospital and came out with a leg three-quarters of an inch shorter than the other one. That was a bad start, so I gave up all pretenses of being a human fly.

Lieutenant Commander [William F.] Halsey was a marvelous battalion officer while I was at the Academy—tough but absolutely square. Everyone loved Bull Halsey. At breakfast formation one morning, I had just jumped into my blue uniform. I can’t remember just why or how. I never did it before and sure as hell didn’t do it afterward. I didn’t even have socks, shirt, or collar on, much less underclothes. Bull Halsey came down, looking with a gimlet eye. He looked at me and said, “Mister, unbutton your uniform.” Gee, there he was, looking at my belly button. I drew 25 demerits for that.

I made the midshipman summer cruise in 1915 in the battleship Ohio [BB-12]. Before we left the harbor in Annapolis, I jumped off the superstructure and got an infection in my left ear. Also along on the cruise were the Missouri [BB-11] and the Wisconsin [BB-9]. That’s where, if you’ll excuse me, the stuff hit the fan. The captain of the Missouri had it all set up to be in command of the first battleship to go through the Panama Canal. By some misunderstanding of the canal personnel, the Ohio slid into the Pacific ahead of the Missouri, and there was hell to pay.

Being recent plebes on the cruise, we drew the worst details. I was assigned to the black gang. We weren’t even on the floor plates of the boiler room. We were back in the bunkers, getting the coal out onto the boiler room floor plates. From Guantánamo, Cuba, onward I was breathing mostly coal dust. When we arrived in San Francisco, we had about ten days there to see the Panama Pacific Exhibition, but then I came down with pneumonia. I was transferred to Mare Island Naval Hospital. My father received a telegram advising, “Your son is not expected to live.” I lived, however.

In 1915 [with war in progress in Europe], Glenn Curtiss set up a school in Buffalo, New York, to train pilots to go to England as instructors. Without consulting my family, I put in an application for this training and was accepted. I wrote my father and told him I wanted to resign. He refused to give his permission. I felt obligated to complete my studies at the Naval Academy.

My hearing went bad when I came up for my next annual exam; I didn’t make the second-class cruise. I was on sick leave for treatment during the summer. I just skimped by the hearing test when I came back in September for second-class year. From that point on, my Naval Academy career was uneventful. I had barely made it in English and Spanish in the first plebe exams. I got a 2.5 in each, and that scared me half to death. Then I started studying—but not too much. Still, in the final class rankings, I was 40th [of 179]. I graduated in June 1917, after a three-year course, and was assigned to the USS Dubuque [PG-17].

In 1921, Tomlinson earned his wings as a naval aviator and in the late 1920s was a member of the Three Seahawks, an aerobatic team that preceded the Blue Angels. He later resigned his regular Navy commission and went into commercial aviation. While working for Transcontinental and Western Air, he was involved with Douglas Aircraft in the testing of the DC-1, DC-2, and DC-3 cargo-passenger planes. The company later became Trans World Airlines.

He and his wife flew via TWA to the 1987 Annapolis visit. At lunch after the interview, Mrs. Tomlinson pulled from her purse some complimentary miniature bottles of vodka she had received during the flight. They added a kick to the Bloody Marys.