Dolphins have been using sound for object detection for millions of years, but the earliest recorded instance of man’s venturing into the realm of hydroacoustics occurred in 1490, when Leonardo da Vinci wrote, “If you cause your ship to stop and place the head of a long tube in the water and place the outer extremity to your ear, you will hear ships at a great distance from you.” A bit ahead of his time, Leonardo had discovered that sound waves travel well in water—better than light or other forms of electromagnetic energy.

The sinking of the Titanic in 1912 revived interest in the complex field and led to the creation of an underwater sound-emitting system that could detect icebergs at a distance of two miles. This led to further research—spurred by the emergence of the submarine—that continued through World War I with the British and French building sound-detection prototypes in 1918, too late for any significant employment in that conflict.

Depth sounding by ships under way was made practical by 1925, and “fathometers” became fairly commonplace. But military applications were relatively slow to develop because of the naval treaties that emerged in that era and because of the need to understand the complex variables (temperature, salinity, pressure, etc.) in underwater acoustics. But by the mid-1930s practical sonar sets were being fitted to both U.S. and British ships.

The British dubbed their early research “supersonics,” but later changed the name to “ASDIC,” supposedly an acronym for Allied Submarine Detection Investigation Committee; however, records indicate no such committee ever existed. After Americans became involved in similar research (much of it in conjunction with the British in the interwar years), “sonar” (Sound Navigation And Ranging) became the standard term.

Active and Passive

Two types of sonar emerged, each with advantages and disadvantages. Active sonar is similar to radar in that it emits sound waves (instead of radio waves) into the water that bounce off “targets.” The returning echoes are then received, with the elapsed time used to calculate distance. Passive sonar relies simply on listening—using some form of hydrophone—to detect sound-emitting targets. Both systems can be adapted to provide bearing information using arrays of hydrophones.

For military purposes, active sonar has the advantage of providing range information but has the disadvantage of revealing the emitter’s presence. It is therefore typically activated by submarines only for limited periods of time and is considered secondary to passive means. Passive sonar does not reveal the user’s presence but cannot provide accurate range information (except through the employment of a sophisticated process called target motion analysis that, over a period of time, uses changes in relative motion and geometry to reveal a target’s range, course, and speed).

Sonar Rating

In the early days of sonar development, a sailor who specialized in sonar technology was called a soundman and designated SoM, with an SoMH specializing in harbor defense. In 1943, the Navy created the sonarman rating (see “Bluejacket’s Manual: Ranks, Rates, and Ratings,” April 2017, p. 6) with the designation SOG (and SOH for the harbor defense specialty). In 1964, the ratings were changed to their current designations of STG for sonar technician (surface) and STS for sonar technician (submarine).

After recruit training, STGs first complete a six-week basic electronics course at Great Lakes, Illinois, before reporting to A school in San Diego for ten more weeks of apprenticeship training. STSs must qualify as submariners and then attend a 37-week Class A school in Groton, Connecticut. Selected individuals receive follow-on advanced training in C schools, lasting anywhere from 27 to 58 weeks and possibly requiring an enlistment extension.

Technological Advancements

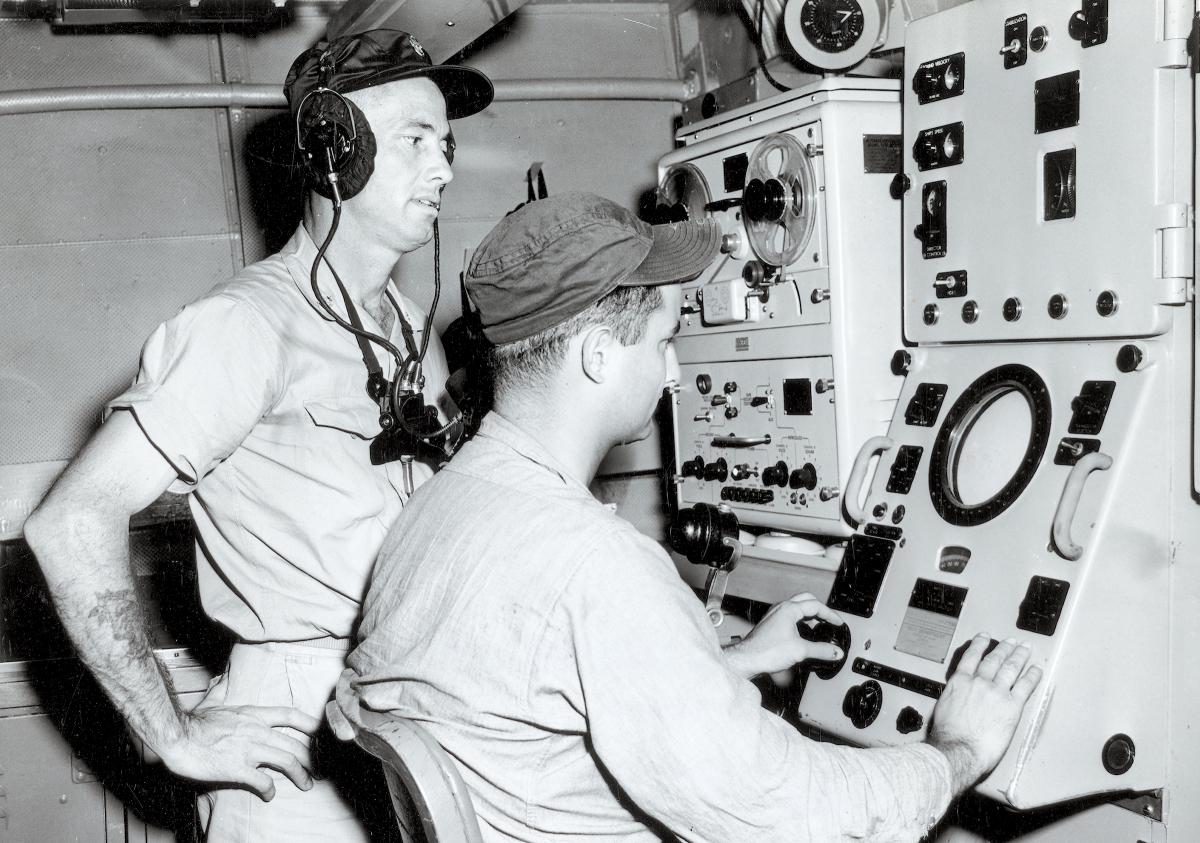

Sonar was used extensively during World War II and became increasingly sophisticated in the postwar years. Hull-mounted sonars were joined by towed arrays and variable-depth sonars (VDS) that were tethered to the ship through reeled cables and could be towed at various depths to reduce the deleterious effects of own-ship noise. Towed arrays are passive, while VDS primarily is active.

Dipping sonars were deployed from hovering helicopters, and the development of sonobuoys vastly improved detection capabilities by allowing aircraft to sow lines or fields of these expendable sensors. Sonobouys remain floating for a time, simultaneously gathering sound data and transmitting it by radio to either ships or aircraft or both. Specially designed explosive devices dropped from an aircraft provides an active sound source whose echoes off targets can be detected by the nearby sonobuoys. During the Cold War, SOSUS (Sound Surveillance System) used a network of bottom-mounted hydrophone arrays connected by underwater cables to facilities ashore to passively detect the presence and movements of Soviet submarines.

The need for antisubmarine and mine-hunting technology continues today, and scientists are engaged in research that either enhances or obviates sonar, sometimes attempting to replicate those highly effective sound systems perfected by dolphins ages ago.