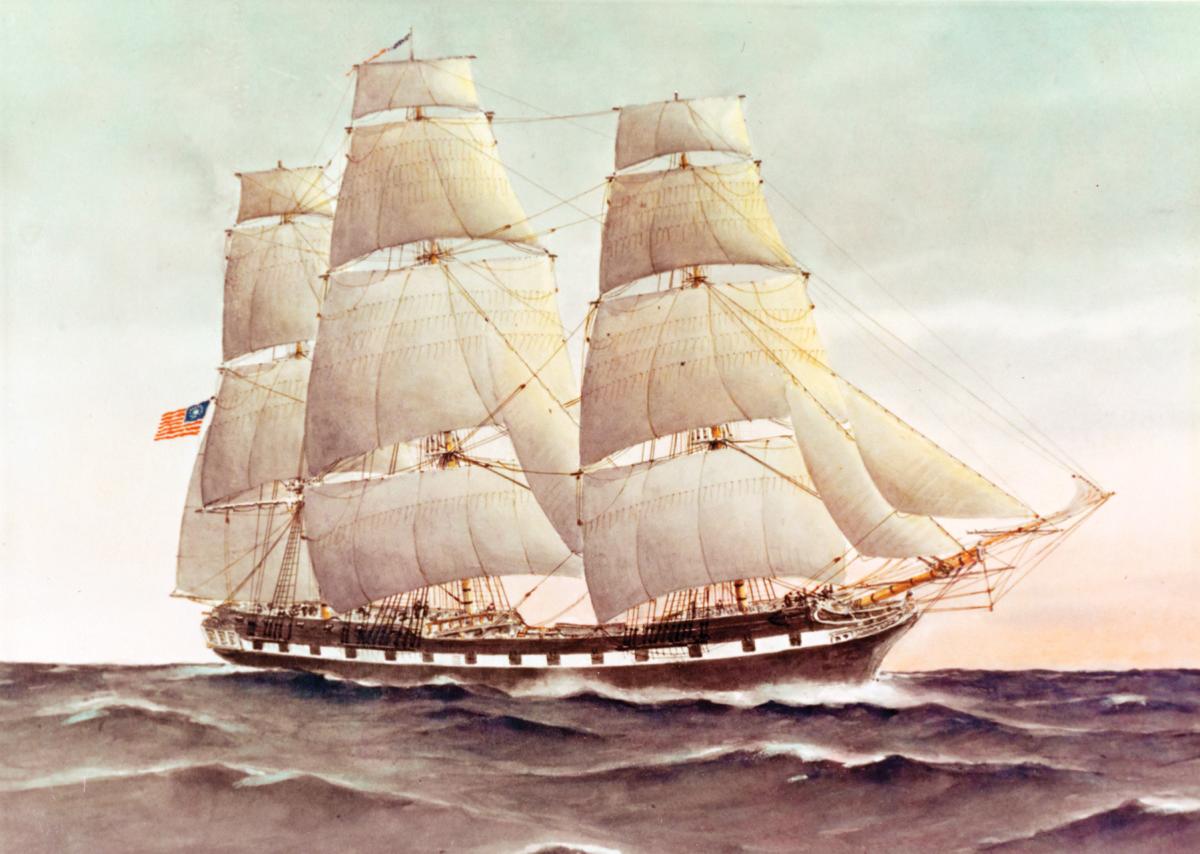

For fully two-thirds of its 244-year existence, the U.S. Navy has counted a warship named Essex among its number. The first, a rated 32-gun frigate armed variously with 40-, 36-, and 32-guns, set a high bar for all that followed.

This Essex was a subscription ship of Salem, Massachusetts, one of a number of ships bought and paid for by local citizenry around the country caught up in the war fever to “oppose French insolence and piracy” during the Quasi-War of 1798–1800. The town raised $74,700 for a ship, which on 23 October 1798 was unanimously voted to be a 32-gun frigate. William Hackett, the designer and builder of the first American frigate, the Alliance, was chosen to design her, and local master shipbuilder Enos Briggs would build her. Over the winter of 1798–99, Briggs advertised for “all true lovers of the Liberty of your Country” who were “in possession of a White Oak Tree” to “be foremost in hurrying down the timber to Salem.”

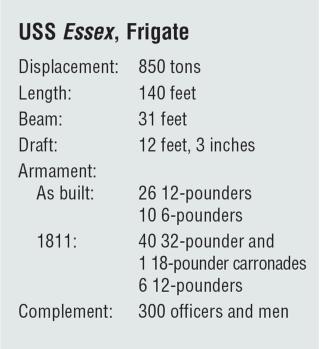

The ship’s keel was laid on 13 April 1799 on Winter Island, one of the few locations on the Salem shoreline capable of launching the 850-ton, 140-foot-long ship. She was the largest vessel and only warship ever built at Salem. Most of the frigate’s components were of local origin. The wood came from nearby forests, the sails were sewn in the town, and the rigging was woven at three local ropewalks. Her copper hull sheathing, however, came from Paul Revere in Boston and her guns—26 12-pounders and 10 6-pounders—from Philadelphia and England. She was launched on 30 September and on 17 December was presented to the United States and accepted by her commander, Captain Edward Preble.

The new ship’s first assignment was not long in coming. Indeed, in early December before the frigate had officially joined the Navy, Preble was ordered to link up with the 38-gun frigate Congress at Newport, Rhode Island, to escort a convoy of ships part way to the East Indies. On 6 January 1800, the two warships left port in company with just three merchantmen. The idea of escorting such a small number of wallowing merchant vessels all the way to Batavia was anathema to the commanders’ warfighting ethos. After just 24 hours, they broke off the escort and proceeded to the Indies on their own.

The two frigates encountered a severe snowstorm that pounded them for several days. The effects of snow and ice on the rigging totally dismasted the Congress; she lost her fore, main, and mizzen masts and bowsprit. After a few days, the crew was able to jury-rig some small masts, which allowed her to limp into Virginia’s Hampton Roads a month later.

The Essex endured the same storm, but Preble reacted differently and saved her masts. In the process, however, he lost contact with the Congress. To save strain on his weakened rigging, the captain ran before the wind on a southerly course but continued to be hammered by gale after gale until, on 9 March, the crew spotted land—Africa. Just two days later, she dropped anchor in Table Bay at Cape Town. After 17 days of repair and resupply, and unwilling to wait for the Congress, she departed for Batavia accompanied by the British sloop-of-war HMS Rattlesnake.

The captains of the Royal Navy’s Indian Ocean Squadron at Cape Town were greatly impressed by the Essex’s lines and wanted to see if she sailed as well as she looked. William Mumford, the ship’s purser, wrote, “to their great Mortification we ran her Hull down in about four Hours.” Arriving in Sunda Strait, the Essex encountered two more British warships, the 74-gun Arrogant and 32-gun Orpheus, of which both challenged her to a test of speed. Both ships were humbled, and their captains forwarded their congratulations. Preble simply noted that his ship was “infinitely faster than either of them.” The frigate anchored at Batavia on 15 May.

There, Preble posted a notice to all American captains that the Essex would sail for the United States on 10 June and accompany any ships then ready to sail “all the way home.” It took until the 18th for the ships to be ready, but on that date the convoy of a dozen merchantmen left Batavia with the frigate as their shepherd. On 28 November, the Essex dropped anchor in New York Harbor, completing her mission, which included her becoming the first U.S. warship to make a double passage around the Cape of Good Hope.

The voyage had not been uneventful, as the frigate briefly chased the elusive French privateer Robert Surcouf and his Confiance. But the Essex, despite not firing a single broadside, had demonstrated that the U.S. Navy could project its power literally around the world to protect trade on any of the high seas.

Later, under Captain William Bainbridge, the Essex sailed in Commodore Richard Dale’s squadron to the Mediterranean. There, from July 1801 to about July 1802, she protected U.S. merchantmen from the Barbary powers. During 1802 repairs at the Washington Navy Yard, her masts were restepped and guns were added, with most long guns replaced by carronades—both to the detriment of her sailing qualities. She returned to the Mediterranean under Captain James Barron in August 1804 and remained there until the conclusion of the First Barbary War in 1805.

Returning to the Washington Navy Yard, she was placed in and out of ordinary until the start of the War of 1812, when, under Captain David Porter, she made a lasting impression on the U.S. Navy. On 11 July, during her first cruise of the war, she captured a British transport near Bermuda and the next month, after a brief battle, captured the 18-gun sloop HMS Alert. By the time she returned to New York in September, she had taken ten prizes.

On 27 October, the Essex set out from Philadelphia on what was to become one of the epic voyages of a U.S. Navy warship. She was to rendezvous with the Constitution and Hornet in the South Atlantic to raid British shipping. Unable to make contact, Porter continued south and in January 1813 rounded Cape Horn into the South Pacific, the first U.S. warship to do so. She battled through fierce storms and seized a British whaling schooner and a Peruvian warship before reaching Valparaiso, Chile, a neutral port, on 14 March 1813. There, the crew made necessary repairs and obtained much-needed provisions.

Sailing north to the Galapagos Islands in search of British whalers, the Essex became the scourge of the British Pacific whaling fleet over the next five months. She claimed 13 prizes, a dozen of them whalers, which amounted to a loss of some $2.5 million (about $40 million in 2020) for the British. That fall, after a year at sea, both ship and crew needed a respite. Porter sailed her far to the west, to Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas Islands, nearly 4,000 miles from the Galapagos Islands. There, the crew overhauled the rigging, scraped the ship’s bottom, smoked out a rat infestation, and rested the crew. They remained there from 25 October to 13 December.

Rather than continue to Sunda Strait, Porter chose to return to the southeastern Pacific in search of more whalers. He made port once again in Valparaiso on 3 February 1814, accompanied by the Essex Junior, a prize that had subsequently been armed with ten 6-pounders and ten 18-pounder carronades. Unfortunately for Porter and the Essex, the Royal Navy had been hunting for them. Among the British ships were the 36-gun frigate Phoebe and an accompanying sloop, the 18-gun Cherub.

On 8 February, a lookout on board the Phoebe spotted the Essex’s masts, leading Captain James Hillyar, the frigate commander and commodore of the two-ship squadron, to order immediate entry into the port. When passing within hailing distance of the Essex, Hillyar assured the Americans he would not violate the sanctity of Valparaiso’s neutrality. The British did as they said and simply replenished their stores and eventually left the port. They did, however, position themselves in the outer bay, out of neutral waters, waiting for the U.S. ships to leave.

The stalemate continued for almost six weeks. Porter was wary of additional warships joining the blockading squadron and made several attempts to escape. On 28 March, he made one final try. At the most inopportune moment, a sudden squall blew up, taking with it the Essex’s main topmast, which greatly affected her maneuverability. The Phoebe could then dictate the battle, and this she did by standing off. Although the Essex was armed with more guns, the majority were short-range carronades. The Phoebe’s long-barrel 18-pounders could range effectively out to a mile. Porter had only six long 12-pounders with which to reply. After two hours of battle, with the Essex badly damaged and having lost 155 of her 300-man crew, Porter struck her colors.

The battle did not end there. Porter, in an official published account, took the British captain to task, declaring that at the time of the attack the Essex had been in neutral waters and that the Phoebe continued to fire on his ship after she had surrendered. Hillyar disputed the accusations.

Although the Essex’s loss was a defeat for the U.S. Navy, her epic voyage was not. The frigate’s 17-month, 27,000-mile cruise showed the ability of a warship in the Age of Sail to operate independently over long distances and periods of time. It further demonstrated the impact a single warship could have on maritime trade and the difficulty in tracking down such a commerce raider.

As for the Essex, the British repaired her and sent her to England, where in 1817 she was reclassified as a 42-gun ship. Despite that, she was never refitted for combat and became a troopship in June 1819. She was hulked at Cork, Ireland, as a convict ship in October 1823 and sold at public auction on 8 July 1837.