Captain Walter V. R. Vieweg, commanding officer (CO) of the USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73), was living a carrier nightmare: During daylight, his ship was caught by a vastly superior surface force with no chance to escape the faster enemy. Surface ships catching an aircraft carrier had happened only once before, when German battleships sank HMS Glorious off Norway in 1940. The time was 0645 on 25 October 1944.

Vieweg—nicknamed “Bowser” for his pugnacious personality—had intrigued his 1924 U.S. Naval Academy classmates, who noted his fondness for animals and his fierceness as a wrestling champion. But he possessed a cerebral aspect, finishing in the top one-sixth of his class, and often cited his motto, “Use your gonk and you can do anything.”1

That Wednesday off Samar, Bowser Vieweg used his “gonk” and did what he could: He turned toward a rain squall while launching aircraft. The Gambier Bay was teamed with five other escort carriers supporting U.S. Army forces on the Philippine island of Leyte. The sprawling Battle of Leyte Gulf, begun so successfully two days before, had turned to hash for Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague’s task unit, known by its callsign, Taffy 3.

Two other escort groups, Taffy 1 and 2, operated nearby, but Taffy 3 largely was on its own. Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita’s powerful battleship-cruiser force of 23 fast men-of-war was bearing down on Sprague’s tiny unit, which was supported by only seven destroyers and destroyer escorts. Something had gone dreadfully wrong.

After the battle, it become clear that Admiral William F. Halsey’s Third Fleet had left San Bernardino Strait unguarded while pursuing Japanese carriers far to the north. Kurita’s 4 battleships, 8 cruisers, and 11 destroyers had been tracked eastbound through the strait on their way to Leyte Gulf and vulnerable U.S. transports, but the night-flying TBM Avengers’ report went unheeded by Halsey and his fast carrier commander, Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher. Taffy 3 paid the interest on that debt.

The Gambier Bay embarked Composite Squadron (VC) Ten, with TBM-1C Avenger scout bombers and FM-2 Wildcat fighters. The VC-10 skipper, Lieutenant Commander Edward J. Huxtable, was sitting alone in the wardroom when general quarters (GQ) had sounded. He recalled, “My immediate thought was, here’s another hop to the Sulu Sea.” Just then, Lieutenant (junior grade) John Holland, rushed in. Using the term in vogue for squadron COs, Holland said: “Captain, you’d better get up to the ready room in a hurry. They’re already manning planes!”

Huxtable followed Holland into the passageway at a dead run. He asked what was happening. “I don’t know,” Holland replied, “but all hell must be busting loose.”

Proceeding to the flight deck, Huxtable was wondering what the rush was all about when he heard “what seemed to be a rifle shot next to my left ear.” He turned his head around to see a salvo of shells explode not far from the White Plains (CVE-66). The urgency was now chillingly clear.2

Launch ’Em

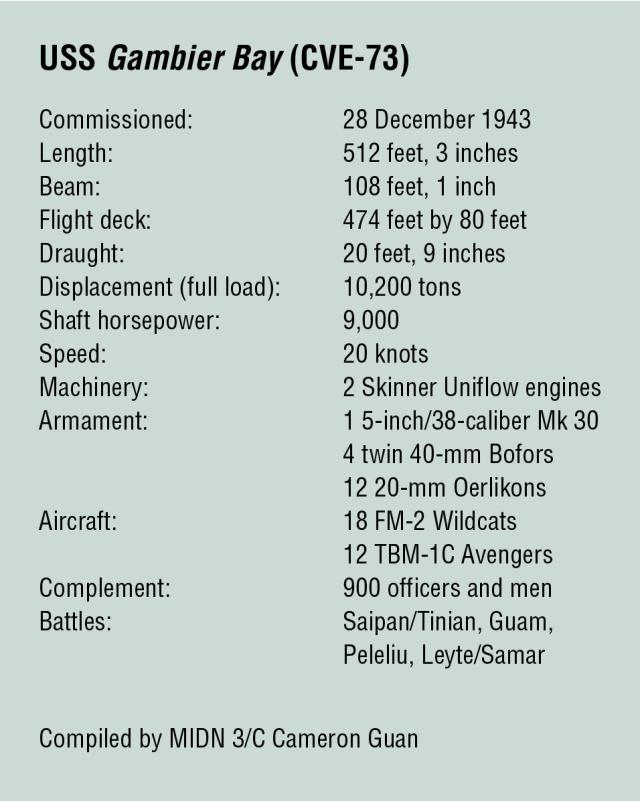

In about 15 minutes, the Gambier Bay launched ten fighters and seven bombers, followed by two torpedo-armed Avengers. With the wind quartering from port it was a little tricky, and the enemy salvos were falling closer. Some of the Wildcats skidded across the deck as nearby explosions jarred the CVE’s light hull. But they all made it off.

Lieutenant Richard Roby’s four-plane fighter division was the first airborne. Ensign Charles Dugan had barely started to crank up his wheels when he got his first look at the Japanese force closing from astern and exclaimed, “Oh, shit!”3

There had been a foot race to man aircraft amid the chaos. A Wildcat pilot, 20-year-old Ensign Joseph D. McGraw, had downed three Japanese planes to date. He recalled:

I just beat my wingman, Ensign Leo Zeola, to the last fighter on the port side aft corner of the flight deck. In fact, it was my airplane, “Baker Six.” I got it started and then had to wait for all the aircraft ahead of me to take off, so I sat there counting shell splashes and getting in some quality prayer time!

I got off as the last fighter, I think, as I had to dodge a big hole in the forward port corner of the deck just as Captain Vieweg was throwing the ship into a turn. I seem to remember that the flight deck officer tried to get me to taxi all the way up to an area he had chosen as the proper takeoff spot, but I poured on the coal, waved him out of the way and took off as soon as I saw the deck clear in front of me. That gave me a better chance to avoid the holes forward.4

The next day, flying from the Manila Bay, McGraw would down two more aircraft to make ace.

Though dozens of planes from Taffy 3 and other groups were airborne, the low ceiling required most pilots to remain below 2,000 feet, limiting their visibility and effectiveness. Aircrews reported some bomb and torpedo hits on the nearest cruisers, and one turned out of line. However, some planes launched without ordnance, so many aviators made “dry” passes to distract the Japanese.

Meanwhile, Taffy 3 continued desperate measures. Vieweg reported:

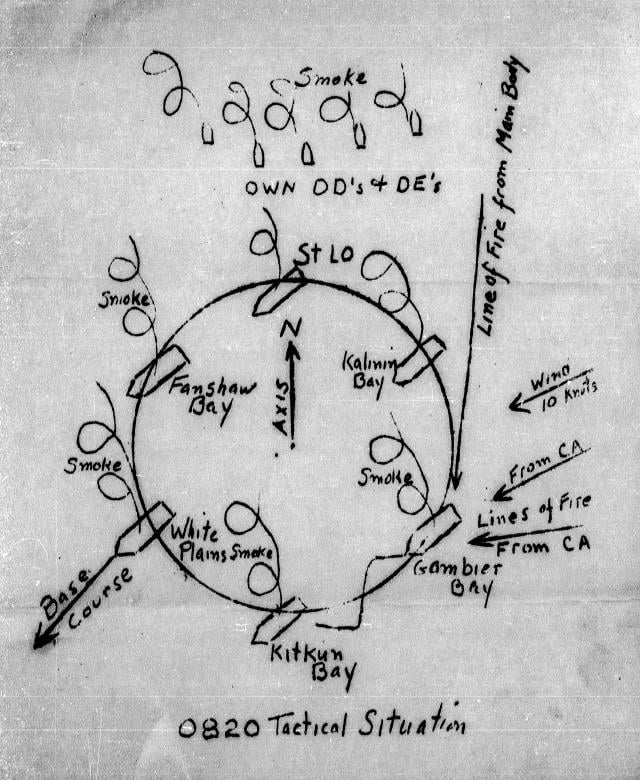

All ships in this task unit . . . made an effective volume of smoke, which undoubtedly in combination with a rain squall, adversely affected the enemy’s gunnery and caused a reduction of damage to all CVEs, particularly from heavy guns of the enemy’s main body. Smoke, however, offered no protection to this ship from the fire of the cruisers on our eastern, windward flank.5

The skipper added, “Meanwhile, a part of the enemy force had turned our flank and were closing the range from northeast.

While the destroyers and destroyer escorts executed one of the U.S. Navy’s most gallantly lopsided actions against Kurita’s much larger ships, losing three of their number, Japanese gunfire continued almost unabated.

The Gambier Bay was subjected to “a heavy and disastrous fire from 8-inch guns,” Vieweg reported, in addition to battleship salvos from the north. She was hit at least 15 times between 0810 and 0850. The most telling hits punctured boilers, opened a hole in the forward engine room that began heavy flooding, and destroyed steering.6

The ship’s log was lost, but officers reconstructed the essentials from memory for the Gambier Bay’s loss of ship report:

At 0837 steering control forward was lost as a result of a direct hit on the pilot house. Control was shifted to Battle II which a few minutes later lost control, with left rudder on, as a result of failure of all ship’s power.

At 0840 a shell entered number three boiler in the after engine room, all steam pressure was lost and at 0845 the ship was dead in the water, devoid of all power, and sinking.7

Abandon Ship

Around 0850, Vieweg heard an exchange between his executive officer, Commander Richard “Smiley” Ballinger, and signal chief Andrew Lindow. They speculated about “getting the boys off,” and Vieweg took in the scene. His ship was coasting to a stop, smoke and flames were rising from the deck, the carrier’s list was increasing, and the aggressive enemy cruisers were closing in, firing from pointblank range. He said to pass the word: Abandon ship.

The order spread quickly, with men going over the side in growing numbers. Aviation Ordnanceman Third Class Nordeen “Skinny” Iverson helped keep two young sailors afloat until help arrived. A strong swimmer from his Idaho childhood, he had lived on Lake Coeur d’Alene.

At 0855, Vieweg ordered Lieutenant Commander George Gellhorn off. The navigator went down the starboard side of the bridge via a lifeline and hit the water just as another salvo pierced the island structure. He identified a still-firing Mogami-class cruiser 2,000 yards away taking a parallel course, compounding the noise, fright, and confusion.

In about five minutes, most of the crew was in the water. Survivors remembered a line of heads strung out behind the ship, resembling a collection of coconuts floating in the ship’s wake. The Gambier Bay’s forward motion had not quite dissipated before abandon ship was completed.

Amid the confusion and terror were vignettes of humor. Recalled Yeoman Second Class Marshall Mitchell: “We pulled over to where there was another floater net and a life raft. There were four wounded men on these; some of them badly wounded. Lt. Comdr. Gellhorn was on one of the nets and I will never forget a remark he said to one of the boys. He said, “Well, Barry, I have had everything but child-birth happen to me now.”8

Dick Ballinger was swimming away from the ship with a young sailor who saw some reason for optimism. He said, “Commander, this means thirty days survivor’s leave, doesn’t it?”

Chief Machinist’s Mate Walt Flanders was among the last to abandon ship. He was standing on the flight deck with three or four others, preparing to jump, when he saw Steward’s Mate John Lovett at the deck edge. Lovett was looking down to the water where the catwalk had been blasted away. Although wearing a life jacket, he was reluctant to jump and kept exclaiming that he couldn’t swim.

Flanders, who knew Lovett had no chance if he remained on the ship, pushed him overboard. A strong swimmer from his youth, Flanders quickly followed him into the water and swam steadily away from the carrier. He passed several swimmers, pulling ahead of most until he was nearly exhausted. When he stopped to shake the saltwater from his eyes, he saw Lovett cruise past him at a steady clip, still loudly insisting he couldn’t swim.9

Ordnancemen in the water urged survivors to get as far away as possible. A torpedo-armed Avenger on one of the carrier’s elevators posed a grave danger and exploded with violent force, detonating stored bombs. Minutes later, at 0907, the ship capsized to port.

With her keel exposed to the sky, the men nearest to the carrier could clearly see the underwater damage she had sustained. Several shell holes were visible, and the port screw was gone,

The Gambier Bay remained floating inverted only four minutes before succumbing. Her hull was so evenly perforated that she dropped straight down without rolling to either side or dipping her bow or stern.

One hour and one minute had elapsed since she received the first hit. From her commissioning day at Astoria, Oregon, to this Wednesday off Samar, her career had lasted three days less than ten months. In all, the Gambier Bay lost 131 men from 900 on board. Most were rescued during the next two days and began the long trek home.

Off Samar, Kurita had gripped Taffy 3 by the throat, fully capable of destroying the entire task unit. But at 0925, Clifton Sprague in the Fanshaw Bay (CVE-70) heard a signalman shout, “They’re getting away!” The admiral could scarcely believe his eyes—the Japanese were reversing helm. Aircraft reports confirmed the reprieve to Sprague, who attributed Taffy 3’s survival to the torpedo counterattack by the destroyers and destroyer escorts, constant aircraft action, “and the definite partiality of Almighty God.”10

Takeo Kurita had lost three cruisers, and the swarming—often unarmed—CVE planes convinced him that he faced a fast carrier task group. Thus, he abandoned the chase to preserve his force.

However, in addition to three escorts sunk defending the carriers, the Japanese response took another dimension. Later that morning, a Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter dove into the flight deck of Taffy 3’s USS St. Lo (CVE-63), exploding with fatal results. The carrier went down in 30 minutes. Kamikazes had arrived.

Debrief

In his 32-page after-action report, Captain Vieweg set the stage for an enduring postwar controversy:

[I]t would appear that the enemy was able to steam through San Bernardino Strait and proceed toward Leyte unreported and unmolested until first met, reported, and engaged by this task unit. That this could be possible seems incredible at first. However, . . . it appears that the divided chains of command for the naval forces in and near the Philippines for this operation may have been conducive to producing just such a situation.”11

Rear Admiral Ralph Ofstie, commander of Taffy 2, listed several mostly self-evident matériel and operational faults. They included: “CVEs are not ‘hard.’ For all practical purposes they are converted merchant hulls. They have little of the compartmentation and generally heavy structure of normal combatant vessels designed to absorb punishment.” He also noted that task units frequently were “pickup” organizations with little opportunity to train together.12

Nonetheless, on 25 October 1944, Clifton Sprague’s little pickup team squared off with the Tokyo giants and scored a triumph. The Gambier Bay’s hard-fighting crew fully justified Bowser Vieweg’s confidence in them.

1. U.S. Naval Academy Lucky Bag, 1924, p. 284.

2. Author interview with CAPT Edward J. Huxtable, USN (Ret.), 1977.

3. Author interview with Charles J. Dugan, 1977.

4. Author interview with CAPT Joseph D. McGraw, 1977.

5. USS Gambier Bay Action Report, 27 November 1944, RG 38, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD (hereafter NARA), 27.

6. USS Gambier Bay Loss of Ship Report, 6 November 1944, RG 38, NARA, 2.

7. Ibid.

8. “The Personal Experience of Marshall L. Mitchell, Y2C.”

9. Author interviews with RADM Richard R. Ballinger, USN (Ret.), and Walter Flanders, 1977.

10. Samuel Eliot Morison, Leyte, June 1944 to January 1945, vol. 12, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (Edison, NJ: Castle Books, 2001), 267.

11. USS Gambier Bay Action Report, 31.

12. USS Gambier Bay Loss of Ship Report, 3.