World War II and the following decade marked a period of intensive aircraft development: turbojet and rocket propulsion, flying wings, parasite fighters and reconnaissance planes, and ten-engine bombers, among other innovations.1 Most of these efforts were successful. But the XF5U-1—called the “flying pancake”—was an abject failure.

The Chance Vought Division of United Aircraft Corporation and its predecessor firms had provided the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps with many aircraft prior to development of the flying pancake.2 The most notable of these was the F4U Corsair—probably the most capable carrier fighter flown by any nation in World War II—with the Corsair serving in U.S. and foreign air forces from 1942 into the 1970s.

The F5U program was initiated in mid-1939, with Charles H. Zimmerman as senior designer.3 He was known for pioneering experimental designs, and he spent most of his career with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and its successor, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). He believed that by maintaining a uniform airflow over the entire wingspan (or “pancake” fuselage), the aircraft could take off and land at exceptionally low speeds and still have desirable high-speed performance. These qualities seemed to be especially desirable for Navy fighter aircraft operating from aircraft carriers.

The aircraft design consisted of a flat, disc-shaped “wing/fuselage” serving as the aircraft’s lifting surface. Two piston engines buried in the body, `1on each side of the cockpit, powered propellers at the leading edge of the pancake. This unusual configuration gave the promise of both high and low flight speeds, with high-angle attitudes for landing, takeoff, and other maneuvers. The wing/fuselage had a complex empennage consisting of two normal-looking horizontal stabilizers and elevators, two rudders, and two large elevators on the midpoint of the fuselage.

Chance Vought built a development, quarter-scale aircraft designated V-173 with a loaded weight of 3,050 pounds, approximately one-fifth the weight of the full-size aircraft. The V-173 flew for the first time on 23 November 1942, following extensive wind-tunnel tests. Among those who flew the V-173 were Charles A. Lindbergh and several Navy pilots. These 131 hours of flight tests were successful, although the aircraft was underpowered.

The V-173’s tall undercarriage gave the aircraft a ground angle of 22.25 degrees, and the pilot entered the aircraft beneath the cockpit. At that angle, forward visibility was almost nonexistent until the tail lifted from the runway. Transparent panels were provided between the pilot’s feet for downward vision during landing. The V-173 normally could take off within 200 feet and could take off vertically into a 25-knot wind.

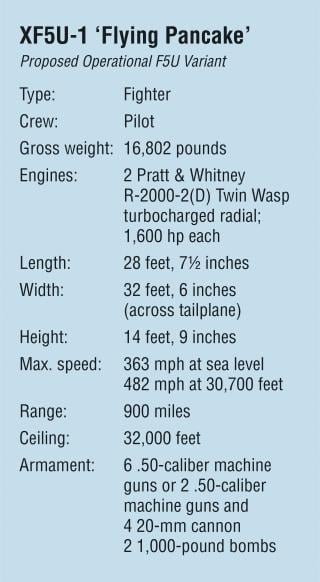

By mid-1942, work was under way on the enlarged VS-315—which would become the Navy’s XF5U-1. In September 1942, the Navy advised Chance Vought of its intent to procure two of the planes. For the operational aircraft, designer Zimmerman sought the phenomenal speed range of 40 to 425 miles per hour; with improved engines and water injection, he envisioned a speed range of 40 to 460 miles per hour.

The engine arrangement presented the Chance Vought team with the most serious problems of the aircraft’s development program. The propellers, which rotated in opposite directions, were attached to shafts enclosed by circular nacelles extending forward from the fuselage. In addition, because of the high angles of attack that the aircraft was intended to adopt for protracted periods, careful attention had to be given to the design of the fuel and oil systems to ensure they would operate at all attitudes for indefinite periods.

Generally similar in configuration to the V-173, the XF5U-1 would sit at an angle of 18.75 degrees; while that was less of an angle than the prototype, it still was severe. The oleo legs each had twin, small-diameter wheels, which folded upward and aft into the lower fuselage surface to be enclosed by clamshell doors. An arresting hook would be fitted for carrier operations; it was a complex assembly that retracted and was enclosed by doors.

As a combat aircraft, the XF5U-1 would have three .50-caliber machine guns mounted on each side of the cockpit, with a magazine capacity of 400 rounds per gun. There were to be provisions for replacing four of these guns with four 20-mm cannon. Two 1,000-pound bombs would be carried under the fuselage.

A wooden mockup of the aircraft was ready for inspection by the Bureau of Aeronautics on 7 June 1943, at Stratford, Connecticut. After some revisions, it was approved in August, although the two-aircraft contract was not signed until 15 July 1944. The first aircraft would have R-2000-77 engines rated at 1,350 horsepower for takeoff, and the second would have the XR-2000-2 fitted with Wright turbosuperchargers. The 16-foot-diameter propellers were contrarotating, turning outboard to avoid prop wash from disrupting the air flow over the wing/fuselage.

The first XF5U-1 was rolled out of the assembly hall at Stratford in late June 1945. It began ground testing on 20 August, with flight testing envisioned to start a year later. The second XF5U-1 would be used for static tests. The flight test schedule was delayed because of difficulty obtaining the articulated propellers, which were not available until 1947. In addition, there were vibration problems and issues with the complex gearboxes. The flight tests were to be conducted at the Muroc Dry Lake in California.

With the end of World War II in August 1945, the Navy reviewed its aircraft development and procurement efforts, with the XF5U an obvious target for cancellation. Beyond financial shortfalls in naval aviation, the Navy was sponsoring several fighter and attack aircraft with turboprop and turbojet engines. Thus, the future role of a piston-engine combat aircraft was highly questionable.The Navy canceled the program on 17 March 1947, issuing orders to scrap the two aircraft, an action that was taken in 1948. The flying pancake never flew. (The V-173 flying prototype was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution and on to the National Air and Space Museum.)

1. Several variants of the Convair B-36 Peacemaker were fitted with six piston and four turbojet engines.

2. The Navy never assigned a “popular name” to the aircraft; its shape led to “flying pancake” being universally applied by all who saw it.

3. This column is based in part on the article “The Untossed Pancake: The Story of the

Ill-Fated XF5U-1,” Air Enthusiast (June 1973): 287−93.