In the spring of 1747, France sent a convoy of 30 merchantmen to bring reinforcements and supplies to its beleaguered troops in North America. The War of the Austrian Succession was not going well for France, and its possessions in Canada were under threat. The convoy left in secret, escorted by a naval force that included four ships-of-the-line. Unfortunately for the French, word had leaked to the British, and a squadron from the Channel Fleet had been dispatched to intercept the convoy. On 14 May, the two forces met off Cape Finisterre in Spain. The French warships fought bravely to protect their charges, but badly outnumbered, they were defeated decisively.

This minor action might have passed unnoticed by all but the most conscientious of naval historians if it were not the first time that a new type of warship was used in combat. The Royal Navy had considerable difficulty defeating one of the French vessels, a large two-decked ship-of-the-line appropriately called the Invincible. She put up such heroic resistance that no fewer than six Royal Navy ships were required to defeat her. The Invincible was of a revolutionary new French design that would go on to dominate the navies of the world. Like all ships of the time, her class was identified by the number of guns that she carried on her main decks—74 in this case.

The British commander, Vice Admiral George Anson, was very impressed with his captured French prize. He wrote about her in glowing terms to the Board of Admiralty, comparing her with his own flagship, the 90-gun second-rate Prince George. The Invincible was seven feet longer and two feet wider, and he calculated almost 200 tons greater displacement. In spite of having two gun decks—instead of his flagship’s three—and carrying fewer cannon, she packed a greater punch. For reasons of stability, three-deckers could carry only light cannon on their highest deck, adding little to their firepower. The greater number of heavy pieces carried on the Invincible’s lower decks more than outweighed the additional guns on the Prince George.

But it was not just her cannon that impressed Anson. Because she had only two decks, the French 74 had a lower, sleeker profile than his towering flagship. This made her faster, more maneuverable, and very stable. He noted that she carried her lower-deck guns higher above the surface of the sea, too, remarking that this could prove a vital advantage in a fleet action fought in poor weather, when ships like the Prince George might not be able to open their lower-deck gun ports.

In this new French ship, Anson had seen the future. His recommendations were clear. The Royal Navy’s fleet should be built around 74s. He naturally met with some resistance to change, in particular the notion that the Royal Navy should be copying the designs of its French enemies. But when Anson became First Lord of the Admiralty in 1751, he was able to force through the adoption of this new class.

What was so special about a 74? All warship design is based on compromise. On the one hand, those who serve on board want maximum firepower, protection, speed, and comfort. On the other, those who design ships (and those who pay for them) point to the necessity of compromise in the limited space of a given hull. In the age of sail, the 74 came closest to achieving the perfect balance of power, sailing qualities, and economy.

The ultimate arbiter of the outcome of fleet actions in the latter half of the 18th century was the 32-pounder cannon (36 in the French and Spanish navies), known in the Royal Navy as “ship-smashers.” Larger guns existed—Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson’s first rate HMS Victory, for example, initially had 42-pounders. But these soon were replaced by the lighter weapon, because the extra weight of the ball, charge, and gun made them much slower to fire, without a sufficient increase in effect. The 32-pounders were the dominant weapon of choice, and a 74 was just big enough to carry them. Smaller two-decked British ships could be equipped only with lighter 24-pounder cannon—and then only on their lower gun decks—and as the century progressed they disappeared from the line of battle.

Navies continued to build larger ships, but these were disproportionately expensive. A wooden ship had a significant number of parts that had to come from a single piece of timber of a particular shape. Knees, for example, which held up the deck, were made from the right-angled joint between a tree trunk and one of its large branches. The bigger the ship, the harder (and more expensive) it became to source these components. Three-decked warships also tended to be slower and less stable than those with two decks. They still had a role to play, particularly as flagships, with additional space to accommodate an admiral and his staff and the extra firepower to protect them, but the majority of the battle fleet would be comprised of 74s.

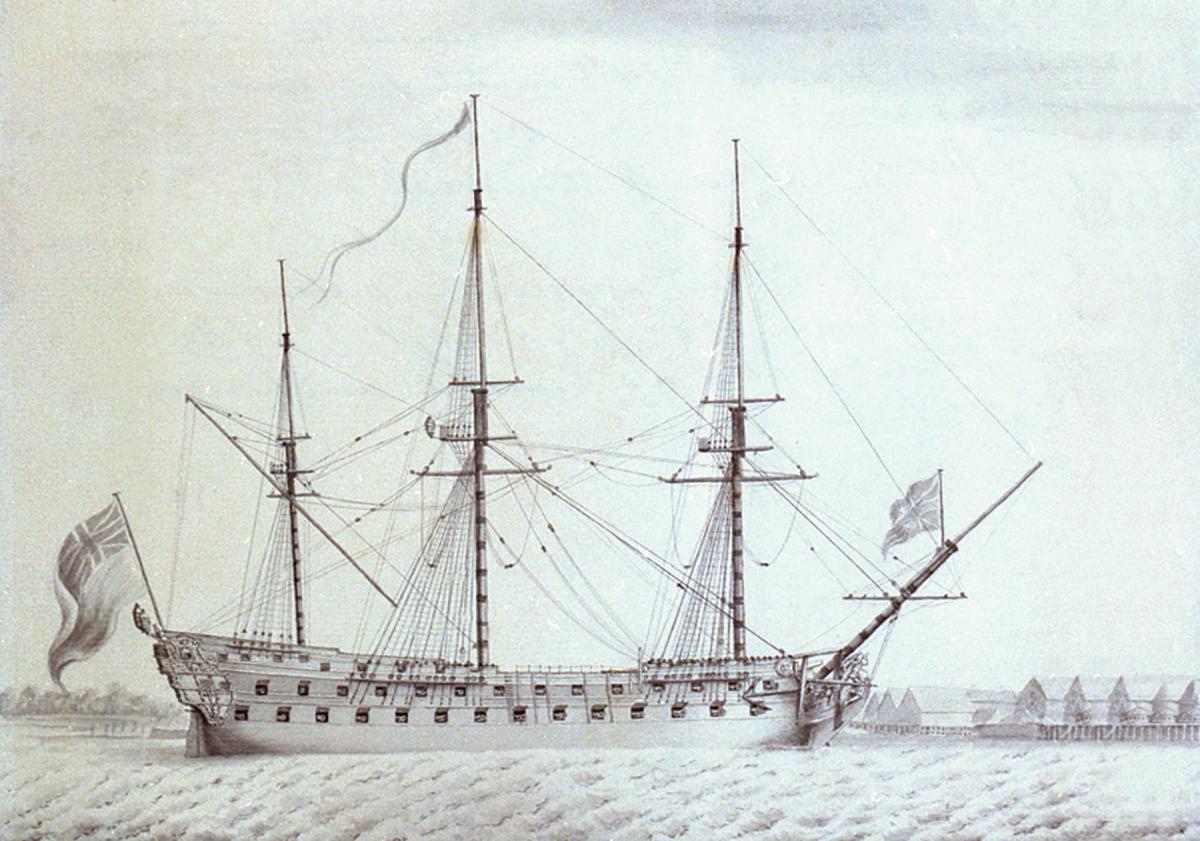

A 74 was an impressive vessel. With a complement of 650 men, she was virtually a floating town, carrying on board specialists and artisans to maintain her and look after the welfare of her crew. In her cavernous hold she carried enough food and water to survive for up to five months at sea. She was propelled by more than two acres of sail held aloft by 24 miles of rigging. The six boats she carried could land her 90 marines on any shore she chose, while on her gun decks she had a greater weight of artillery than the Duke of Wellington’s whole army at Waterloo.

In the second half of the 18th century, the demands on navies were changing, and this, too, played to the strengths of the 74. Naval campaigns at the start of the century were conducted only in summer, largely because of the limitations of the available warships. But this also was a time of rapid change. The European population of the Americas was growing quickly. Trade in commodities—such as tea, coffee, Caribbean sugar, and spices—was of increasing importance. This all combined with the early effects of industrialization to raise steadily the importance of seaborne commerce to the world economy. As a result, blockading an enemy’s ports became a significant strategic weapon, one requiring warships that could stay at sea in poor weather. The new breed of 74s were much better suited to this role than the ships they replaced.

It also was a time when European conflict, particularly among the dominant naval powers of Britain, France, and Spain, was moving out from Europe to the fringes of empire. Significant conflict was occurring between colonists—or, in the case of the American War of Independence, against them. The Caribbean, North America, and the Indian Ocean all saw major naval clashes. It increasingly was the powerful yet weatherly 74s that were sent across thousands of miles of ocean to defend their nation’s interests.

When Anson’s squadron captured the Invincible in 1747, the French Navy possessed all the small handful of 74s in existence. By the end of the century, three-quarters of British ships-of-the-line were 74s, and they had become the backbone of every major European navy. Some notable actions, such as Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile, were achieved exclusively with them—perfect ships indeed.