My recollections of the “broken arrow” accident—when an A-4E Skyhawk loaded with a thermonuclear bomb went over the side of the USS Ticonderoga (CVA-14) on 5 December 1965—are still as vivid as the day it happened.

I had joined the Ticonderoga in March 1964 as an airman apprentice (AA) and was assigned to the guided missiles (GM) division of the weapons department. I had no guided-missile training, so I learned my trade on the job. Our division was a small group of men led by an aviation ordnanceman senior chief and a lieutenant (junior grade), who was an explosive ordnance disposal officer. We were very close, and we gained a lot of expertise in handling, building, and maintaining Sidewinder, Sparrow, Shrike, and Bullpup missiles.

The Ticonderoga was in the South China Sea when, on 2 August 1964, the destroyer USS Maddox (DD-731) reported an attack by three North Vietnamese torpedo boats in the Gulf of Tonkin. The Maddox asked for assistance, and the Ticonderoga responded by launching four F-8 Crusaders armed with Zuni rockets and 20-mm cannons. Two boats were damaged, and one was destroyed. Two days later, the destroyer USS Turner Joy (DD-951) reported being under attack by North Vietnamese torpedo boats. On 5 August, the Ticonderoga again responded: She launched F-8s, but no boats were found. (See “The Truth About Tonkin,” February 2008.)

This led to President Lyndon Johnson signing the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on 7 August, which authorized the President to take military action against North Vietnam. The Ticonderoga remained on Yankee Station for more than 60 days, launching airstrikes until relieved by the USS Ranger (CV-61) in November. (From 1964 to April 1966, “Point Yankee”—more commonly known as Yankee Station—was a position off the coast of Vietnam at 16°00' N, 110°00' E.) We arrived in San Diego on 15 December after having been gone for almost ten months.

In January 1965, the Ticonderoga departed North Island for Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in San Francisco. The ship was scheduled for a yearlong overhaul and maintenance period, but a shortage of West Coast carriers and the escalating war in Vietnam shortened the yard period to six months. During the time in the yard, I and others from the weapons department attended Nuclear Weapons Loading School at North Island, Naval Air Station (NAS) Miramar, and NAS Lemoore.

Back to Vietnam

The aviation units destined to deploy with the “Tico” had completed their qualifications during July and August, an intense training period to say the least. All was ready for the carrier’s second deployment to Vietnam, and on 29 September, she slipped her moorings and proceeded down San Diego Harbor, past Point Loma, on her way to Pearl Harbor. At Pearl, we passed an operational readiness inspection—checking if the ship and crew were ready for combat—without any major hitches. The air wing and all its aircraft were ready.

When we arrived back on Yankee Station, the operational tempo was very high, with flight operations being conducted night and day. I was assigned to the flight deck, checking the missiles our division had provided to the various squadrons. I also had to stand watches, and it was very tiring. At the end of November, the Ticonderoga was relieved of duty in the Gulf of Tonkin with orders to Yokosuka, Japan, for maintenance and rest and recuperation.

The ‘Crew Cut’

While we were proceeding to Yokosuka, the Tico’s commanding officer, Captain Robert N. Miller, authorized a “crew cut”—a nuclear weapon loading exercise.

On Sunday, 5 December 1965, my loading crew assembled in hangar bay No. 2 around 1330. We were 50 miles off the coast of Okinawa. The exercise was to load an A-4E Skyhawk (bureau number 151022) of Attack Squadron (VA) 56 with a nuclear weapon. Plane handlers would then push the airplane onto the No. 2 aircraft elevator, escort the airplane to the flight deck, and put it on the port catapult. Finally, they would return the Skyhawk to the hangar for us to offload the bomb.

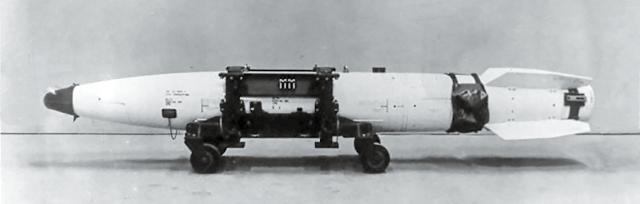

The nuclear weapon arrived in the hangar at 1400 hours. It was covered with a gray tarp, and two Marines with loaded M16 rifles provided a security escort. All six members of my team were standing around, each of us with a checklist to cover the different tasks we had to perform. Mine was to verify the weapon was on “safe” and to report it to the crew chief. The W Division personnel removed the tarp from the weapon, and we all immediately identified it as a live B43 thermonuclear weapon.

We were flabbergasted by what we saw. On the side of the weapon was the symbol Y1, meaning it had a one-megaton yield. Around 1415, W Division turned the weapon over to our crew chief, Aviation Ordnanceman Second Class Tom Chambers, who began to go through the loading checklist with us.

We positioned the weapon under the Skyhawk’s belly using an Aero 33D bomb truck. We hydraulically lifted the B43 into the bomb rack and locked it in. Then the sway braces were adjusted to keep the bomb from swaying. After loading the weapon, our crew withdrew to the side.

The pilot, Lieutenant (junior grade) Douglas Webster, approached his aircraft and began to inspect it—and the weapon. All apparently was in order, and he climbed the ladder to the cockpit. The plane captain followed, to help him strap in and remove the ejection seat safeties. After the captain climbed down and removed the ladder, plane handlers—blue shirts—began to push the Skyhawk by hand onto the No. 2 plane elevator. We all stood by and watched, wanting this exercise to be over so we could offload the weapon, return it to W Division, and get back to our own shop.

The Disaster

Suddenly, the plane directors—yellow shirts—began to blow their whistles frantically while crossing their fists, directing the pilot to set his brakes. But the Skyhawk kept rolling. According to testimony during the post-incident Board of Inquiry investigation, the pilot seemed oblivious to the whistles and was looking down. The directors ran to the plane, urgently signaling and blowing their whistles.

The Skyhawk did not stop. One blue shirt threw a chock around the starboard main mount tire, putting himself in harm’s way to stop the rolling aircraft. Another on the plane’s port side could not get his chock around the tire. As a result, the Skyhawk pivoted to the right as the port main gear mount hit the netting on the aircraft elevator. This caused the main mount to break through the steel netting, and the Skyhawk lifted itself and fell inverted into the ocean.

The other ordnancemen (Doug Wilson and Harald Drews) and I—wondering what was happening—saw the Skyhawk suddenly hit the end of the elevator and fall overboard. We ran onto the elevator. We never saw Lieutenant Webster after he climbed into the cockpit or knew what efforts he might have attempted to get out of the Skyhawk, but we were stunned to witness a plane, pilot, and nuclear weapon fall into the ocean.

As we stood on the elevator, seeing the Skyhawk on its back, its landing gear sticking straight up out of the water like the legs of a giant insect, we wondered what had gone wrong. We watched helplessly as the attack plane and pilot sank into the abyss, the ship continuing to move forward. It was horrifying to watch a human being die before our very eyes, powerless to save him.

The ship finally stopped, and a recovery helicopter circled the area where the Skyhawk fell overboard, but by then it was too late. The destroyers Gridley (DLG-21) and Turner Joy searched for hours for any sign of the pilot, but to no avail. The Ticonderoga launched a motor whaleboat and crew, but all they found was the pilot’s helmet, which he was not wearing when the accident happened.

It has been suggested that Lieutenant Webster tried to get out of the plane before it went overboard, but I saw no evidence of this. With the canopy open, the force of the Skyhawk hitting the water would have seriously injured him as the canopy closed, possibly rendering him unconscious or worse. The fact that the yellow shirts blew their whistles frantically in a seemingly unsuccessful bid to get his attention signifies to me that the pilot was distracted, by what we will never know.

The Aftermath

Sometimes I think back to this incident, and after 54 years, it still haunts me. Navy investigators never interviewed or questioned me or any of the other members of the loading crew about what we saw, how the weapon was loaded, procedures followed, or observations prior to the accident. Nothing. I doubt we could have added much, but we possibly could have dispelled any rumors or innuendos associated with this tragedy.

The magnitude of this event touched many lives. It left a young wife a widow, a mother questioning why her son’s name is not on the Vietnam War Memorial, and a nuclear bomb attached to a plane 16,000 feet deep in the ocean. When the event was publicly acknowledged in 1989, it created an international incident with Japan. Although there is no possible way the bomb could spontaneously detonate, the mere fact that it is there should haunt us.

Fair winds and following seas, Lieutenant (junior grade) Douglas Webster. I, for one, have not forgotten you.