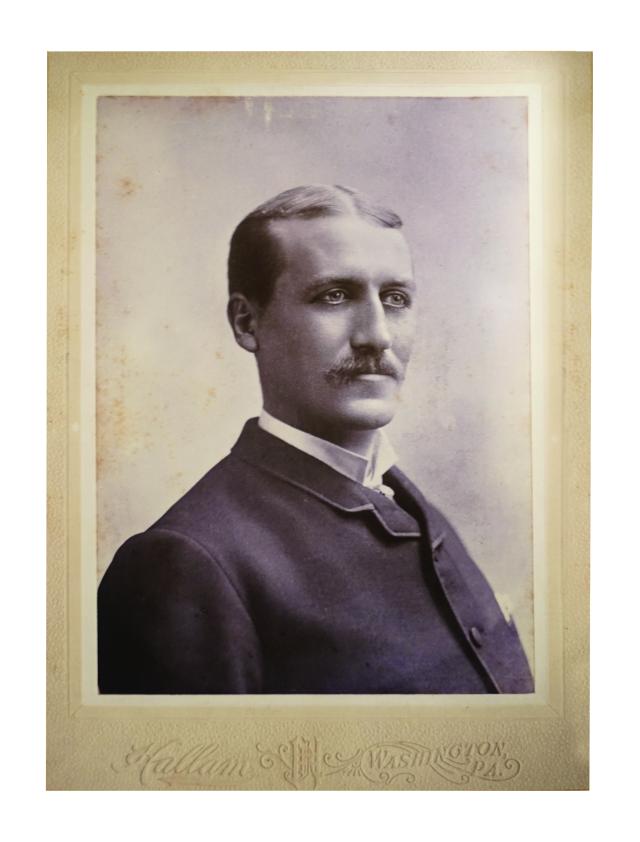

The U.S. Naval Academy Museum’s galleries in Preble Hall are replete with the biggest names in U.S. naval history—James Lawrence, David G. Farragut, Chester W. Nimitz—and, for a limited time, the lesser-known but fascinating Philo N. McGiffin. He is the subject of the museum’s temporary exhibit, “Philo McGiffin: A Man of Wit and Dash.” Bringing artifacts from the museum’s collections together with those of the Washington County (Pennsylvania) Historical Society, the small, two-room exhibit provides a glimpse into the tumultuous world of a man whose humor and tenacity made him the stuff of legend.

McGiffin bore remarkable witness to history. Born in Washington, Pennsylvania, in 1860, he entered the U.S. Naval Academy in 1877. During the course of his studies, his impish yet rebellious nature quickly became known to his classmates and instructors—including Professor Albert A. Michelson, whose 1879 Experimental Determination of the Velocity of Light is on display as part of this exhibit. McGiffin may not have excelled academically, but he did excel in the execution of pranks—conduct that earned him a trip to the brig, a repeated academic year, and a place in Naval Academy lore. Many artifacts from his Academy days, such as his uniform vest, are on display in the exhibit.

By the time McGiffin was ready to be commissioned in 1884, following two years of training cruises, the Navy, in a time of post–Civil War retrenchment, had no more billets to fill, and he was denied a commission. Undeterred, he sought other ways to prove his merit.

He found his opportunity in the long-simmering conflict between China and France for control of northern Vietnam, which had erupted into open conflict in the summer of 1884. Following the economic and internal devastation wrought by the Taiping Rebellion and the Opium Wars, China had embarked on a program of self-strengthening, leveraging Western techniques and technologies to build up its industrial base and professionalize its military as a counter to an increasingly bellicose Japan and encroaching European interests. For its program of modernization, China needed Western militarists, such as McGiffin, to advise and train its people in those weapons, strategy, and tactics. McGiffin proffered his expertise to Chinese Foreign Minister Li Hung-chang.

On Li’s recommendation, McGiffin was commissioned into the Imperial Chinese Navy. After teaching seamanship and gunnery, he was put in charge of planning and building a new Chinese Naval Academy at Wei-Hai-Wei. At the age of 28, McGiffin found himself implementing the very regulations against which he had rebelled to train the next generation of sailors for China’s rapidly expanding navy; the country’s Beiyang (northern ocean) Fleet, with its Western-built ironclads, battleships, and cruisers, was thought to be the strongest in Asia. It was on board one of these vessels that McGiffin would propel himself into the public imagination.

Longstanding tensions over the Korean Peninsula finally brought China and Japan into conflict. On 17 September 1894, the Japanese Combined Fleet met the Beiyang Fleet on the Yalu River. McGiffin, executive officer the battleship Chen Yuen, recounted the harrowing experience of the Chinese sailors as the Beiyang Fleet suffered a staggering strategic defeat. The Chen Yuen and her crew limped into Port Arthur the next day, “a small riddled ensign flying from the starboard signal yardarm on the foremast.” The pennant is on display in the exhibit, along with a Japanese scroll depiction of the battle and models of both the Chen Yuen and the technologically comparable second-class battleship USS Maine, which was commissioned a decade later.

McGiffin’s future was brief. Severely wounded in the face by shrapnel and by the scapegoating of Admiral Ting Ju-ch’ang for the disastrous defeat at the mouth of the Yalu, he resigned his commission in 1895 and sought specialized treatment in the United States. Tormented by memories of the battle and by the possibility of losing his sight from his wounds, the increasingly unstable McGiffin fatally shot himself in February 1897.

While the exhibit focuses primarily on the man himself, the museum’s curators skillfully have woven his story into the larger narrative of his world. Naval Academy graduates will come away with a greater appreciation for the man who has come to embody the pugnacious fighting spirit of the Brigade of Midshipmen. They and others may want to learn more about the brave young man “who loved his own but gave his life for an alien flag.”

“Philo McGiffin: A Man of Wit and Dash” will be on display through the end of 2019.