Fifty years ago, on 23 January 1968, the North Korean Navy opened fire on the U.S. Navy in international waters off North Korea’s east coast in the Sea of Japan. The one-sided battle lasted almost two hours and left one U.S. sailor dead, more than a dozen others injured, the ship captured, and the surviving crew taken hostage. The first shots were fired at about 1332 (local time). The Koreans brought two sub chasers, three torpedo boats, and a couple of MiG fighters to the battle. The U.S. Navy brought the USS Pueblo (AGER-2)—virtually unarmed and outfitted as an electronic surveillance platform.

At the time, I was a 24-year-old lieutenant (j.g.), one of six officers on board the Pueblo, serving as first lieutenant and the ship’s operations officer. (We had a naval security group detachment on board supervised by its own operations officer.) I had the morning watch that day and the day before when we were first approached by North Korean civilian fishing boats. I drafted our initial situation report confirming that contact.

Many criticize the ship for surrendering without firing a shot—absolute heresy in the “Don’t give up the ship” and “I have not yet begun to fight” naval aristocracy. One of the admirals running the 1969 court of inquiry into the loss of the ship told me, “I wish you had fired just one shot.” With North Korea’s opening shot, however, the Pueblo’s main line of defense—the time-honored respect for the freedom of the seas—was blown away.

Within an hour, a fourth of her crew was dead or wounded. What was left was a defenseless ship with no hope of either thwarting the intentions of her attackers or escaping to the open sea.

Cold War Intelligence Game

What Pueblo incident retellings often overlook is the brutality with which the North Koreans, led by then-Premier Kim Il-Sung, changed the Cold War cat-and-mouse game of intelligence collection. Collectively, the U.S. military had grown complacent about the rules: push and counterpush, cajole and threaten, but ultimately one side “blinks” and the game is over. The game wasn’t about victory; it was about intelligence gathering, filling the blank pages in everyone’s electronic order of battle. Knowing the enemy, knowing his limits, and knowing how far he can be pushed. A game of courage and fortitude, but also of judgment and wisdom and years of accumulated experience.

The North Koreans blew away all of that with their opening salvo against the Pueblo. It wasn’t a shot across the bow or rockets screaming low across the waves. It was point-blank and aimed at the pilothouse itself—the nerve center of the command-and-control infrastructure of the ship. That first set of shots knocked out the pilothouse Plexiglas, at least one of our major antennas, and caused minor injuries to many crewmen. And it changed the rules of the game forever.

The Opening Salvo

I was on the bridge at the outset of the confrontation on 23 January. I was fortunate not to be injured when the first shots came through the pilothouse, shattering glass and scattering sailors. Almost immediately, one of my radiomen and I attempted to use the ship’s incinerator to destroy classified material, but since doing so meant exposing ourselves, we spent most of the time dodging bullets.

The second or third salvo blew out our antennas, so we had to rig the emergency antenna. Below decks, I organized and directed the burning of our crypto code cards in trash cans, working with the man who later was killed and the three others who were seriously injured in the attack but survived the explosion of a shell that came through the hull.

The Koreans fired at us multiple times, both with the 57-mm cannons on their sub chasers, and much more frequently with the torpedo boats’ machine guns. The Pueblo’s mostly aluminum skin offered little protection to her sailors; it was riddled with holes, as the larger shells punctured her with impunity. I saw a lot of action but managed to escape without a scratch.

Stalling for Time

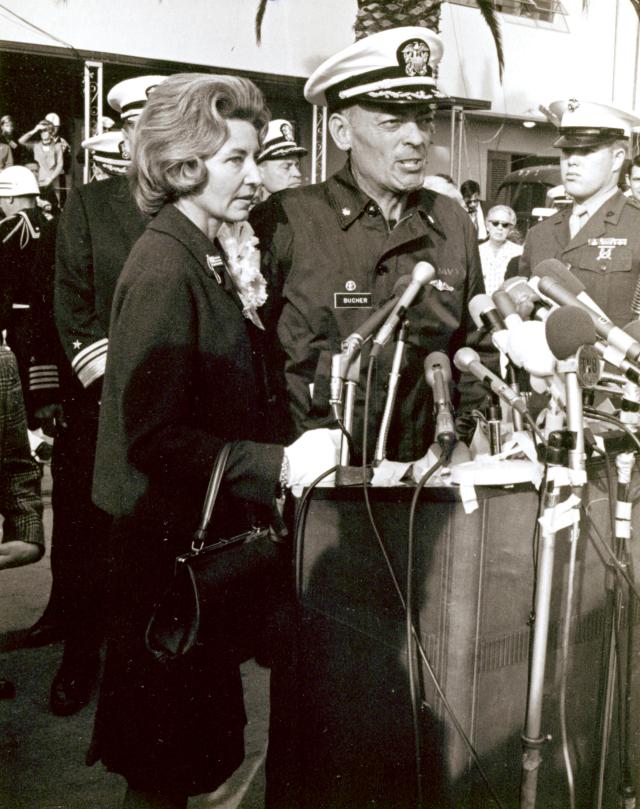

Key decisions that day were made by the Pueblo’s commanding officer, Captain L. M. Bucher, known to all as Pete. A former diesel-boat submarine officer, he was quite familiar with the type of electronic ferret work we (and our sister ship in Japan) were doing and had been briefed to expect some harassment but not open hostility from our principal targets—Russia, China, and North Korea. He was not promised military assistance, and none was planned for this so-called shakedown cruise.

During the gun battle, none of his choices looked good. While the Pueblo did have two .50-caliber machine guns on board (a last-minute addition generated by the Israeli attack on the USS Liberty [AGTR-5] just six months earlier), the rapidly added gun mounts had no armor protection. Other weapons were limited—maybe eight .45-caliber sidearms and a couple of small Thompson machine guns. Enough to dispel normal boarders but not enough to resist the forces we were facing.

With little firepower on board, our strategy was to stall for time—time for the might of the U.S. military to be brought to bear, time for our crew of 83 to complete emergency destruction, time for the North Koreans to realize the foolishness of their brazen attempt to seize a U.S. Navy warship on the high seas.

The North Korean strategy was to corral the ship into its territorial waters and then board and take possession of the Pueblo, her crew, and her contents. Time worked against them since they knew that our military would arrive and that seizing the ship was essential. So, each side had its strategy and maneuvered to the best of its ability.

For us, this meant heading for the open sea at full power—13 knots—not a speed that would allow much distancing, but still a factor since every mile we could gain to the east meant more time needed for the North Koreans to get the ship into port. We maneuvered as best we could to keep the ship headed toward the open sea.

The North Koreans, however, had guns and the willingness to use them. Heading to sea meant we would have to sail right into their gunfire, forcing us to protect life by reversing course and following the vessels toward North Korean waters. Likewise, slowing down, to buy time for us to destroy classified documents and equipment, caused them to encourage us to speed up. As they became wise to our strategy, they focused on the outward signs of our destruction efforts (smoke and bags going over the side of the ship) and directed their gunfire toward those locations.

Ultimately, our choices were eliminated. No running for the open sea, no dawdling on the trip toward Wonsan. For the North Koreans, the clock was running out and they needed to seize the ship in a hurry, before the expected U.S. response arrived. For the Pueblo, the silence from our shore-based commanders was deafening. Despite excellent online, fully encrypted, teletype-based resources and prepared reports from the Pueblo, no instructions were received. The only navy trying to communicate with the Pueblo was North Korean.

And so, the Pueblo was alone, with one dead and many injured, no indication of support or assistance, and an enemy bent on our capture. The final boarding attempt was successful and the ship was hijacked.

Mandate of Resistance

The Pueblo was sailed into Wonsan, where the crew was placed on a train to Pyongyang, North Korea’s capital, and held in a barracks, with officers isolated by themselves and the crew berthed in eight-man rooms. The immediate focus was on Pete, but the beatings we all received were severe. After 24 hours, the officers were told they would be shot at dawn as spies (not captured members of the military).

The captain was repeatedly interrogated, beaten, and told he had to admit his ship was spying, apologize, and give his assurances that he would never do this again (the so-called “three As”). When Pete resisted, the North Koreans put a revolver to his head. Then they said he wasn’t worth a bullet, and they beat him until he was unconscious. Later that night, after he regained consciousness, Pete was shown a severely tortured, barely alive man, a so-called South Korean spy. The captain then was returned to his cell block, where his North Korean captors told him they would shoot his crew in front of him, one by one, starting with the youngest. One of the guards left to retrieve the young sailor, and recalling the tortured South Korean “spy” and contemplating the murder of his crew, Pete capitulated and said he would sign their document.

Our captors dictated the document to him, but when he was done he told them he wanted me to review it for “completeness,” and it was brought to me for editing. My first thought, of course, was to clean it up and put it in proper form, but as I got into it, I realized Pete wanted the language to be even more stilted and archaic and to incorporate as much American and navalese slang as possible.

Since I was new to this, I wasn’t nearly as creative as I would become, but the resulting document was, when it was publicly released, universally denounced as something dictated by the North Koreans and not written by Bucher. So, almost immediately, Pete had created a mandate of resistance that guided us for our 11 months of captivity: using the only weapons we had—the written word and photographs—to do whatever we could to discredit North Korea’s propaganda. This was passed along to the crew, who responded whenever they could in various media over the coming months, with the most notable and remembered being the explanation that the universal sign of derision (the extended middle finger) was the “Hawaiian good luck sign.”

Brutal Beatings, Continued Resistance

Meanwhile, our treatment as captives entailed severe beatings of two types. First were those administered to elicit acceptance of our captors’ various questions and demands. These beatings usually were one-on-one and, in my case at least, carefully administered to avoid damage to my face, which could be revealed in photographs.

After about six weeks in downtown Pyongyang, we were moved to the country, occupying a newer building that had been a military training facility. Here we were guarded by 17-year-old North Korean soldiers raised to detest Americans as their archenemies. They would often, usually at night, inflict their own beatings. These were less severe than those ordered from on high but were just as painful.

During our captivity, I was permitted to spend an hour or so with Pete playing chess. This freedom was short lived, but it did give me a chance to learn of his lengthy (usually about eight hours long) conversations with the colonel (later general) in charge of us. Despite his solid exposure to Western literature and the arts, the colonel maintained that the U.S. Army invaded North Korea, thereby starting the Korean War. Further, our troops remained in Korea only in preparation for another war. Hatred of Americans was widely ingrained, since virtually every North Korean family lost a father, husband, uncle, or son in that war and still wanted revenge. Hence, civilians willingly sacrificed their personal needs (i.e., food) to maintain an army strong enough to resist the United States and our “running dogs” in South Korea. As a part of our “reeducation” we visited their completely fictitious Museum of American Atrocities, where our ship resides today.

Resistance continued as the captives were directed to write numerous letters and confessions. Over the months, our efforts to discredit North Korea’s propaganda efforts succeeded to such a degree that Time magazine published a photo of several crew members and explained the hand gestures several were making. The issue quickly reached the North Koreans and resulted in their attempt to uncover all the tactics in our discrediting campaign. Beatings were administered first to their own translators (the ones who had missed our efforts) and then to us, resulting in what we called “Hell Week,” a ten-day-long wave of brutal beatings and torture. I ended up with a couple of severely bruised ribs, one black and swollen eye, and large bruising and swelling around my left ear and head.

As tough as the beatings were, however, they hurt less since they merely proved how successful we had been at undermining their propaganda efforts.

Emerging from Hell

Hell Week ended with a breakthrough in negotiations, and we rapidly were cleaned up for a walk across the Bridge of No Return to freedom. Pete, however, was asked to record a final departure message. With the drafting committee, which included me, and other officers, Pete recalled the word “paean,” which translates as “praise” but when spoken has a different connotation. His recorded speech was widely broadcast, and his voice boomed out our desire to “paean [pee-on], not just the Korean People’s Army, not just the people of North Korea, but the Korean people’s government, and most of all, Kim Il-Sung.”

The four weeks after our departure were a whirlwind of activities, ending with the launch of the naval court of inquiry, whose proceedings would last six weeks. This was disappointing to us since on the two key points—the “means of resistance” and the destruction of classified materials—the court chose to have further examinations (including our right to call contrary experts) via courts-martial for Commander Bucher and others. Pete wanted a court-martial to develop a more thorough investigation, but the Secretary of the Navy overruled the court’s recommendations, stating there was “plenty of blame to go around” for the incident and that whatever the results, the “crew of the Pueblo has suffered enough.”

The issue of further blame was examined in detail during two congressional hearings, both of which severely criticized the Navy’s planning and lack of support. Nothing happened as a result, except the Pueblo program was eliminated and the three ships involved (out of a planned fleet of 13) were decommissioned. Excluding, of course the USS Pueblo, which is still held by North Korea.

In a sense there never has been closure to the incident. They still have our ship, and though the crew did an extraordinary job during their 11 months of captivity, there has never been a formal apology or official thank you from the Navy.

‘The Fickle Finger of Fate’

Over the course of their imprisonment, the crew of the Pueblo was forced to write numerous confessions and apologies to the Korean people, in which they would insert inane and irreverent language and references to show their resistance. Below is an example of one such confession, signed by Captain Pete Bucher.

A final confession in anticipation of leniency for my crew and myself for the heinous crimes perpetrated by ourselves while conducting horrible outrages against the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea or the purpose of provocating and annoying those stalwarts of peace-loving humanity. The absolute truth of this bowel wrenching confession is attested to by my fervent desire to paean the Korean People’s Army Navy, and their government and to beseech the Korean people to forgive our dastardly deeds unmatched since Attila. I therefore swear the following account to be true on the sacred honor of the Great Speckled Bird.

Following rigorous training in provocation and intrusion wherein each of my officers had to meet the overly high standards I had set for them we emerged from the bowels of San Diego harbor bent on setting records for the highest yardage gained in intrusions ever set in the standard patrol. Our first stop was Hawaii where I visited the kingpin of all provocateurs, including spies. None other than Fleet General Barney Google. He was all I had been told, sly, cunning, closed mouthed, bulbous nosed, smelling of musty top secrets and some foul smelling medicine that kept him going twenty hours a day in pursuit of the perfect spy mission. He talked haltingly with me but persuasively about our forthcoming mission. “By God, Bucher, I want you to get in there and be elusive, spy them out, spy out their water, look sharp for signs of electronic saline water traps. You will be going to spy out the DPRK. By the sainted General Bullmoose we must learn why they are so advanced in the art of people’s defense.”

We entered into our assigned operating areas along the Eastern Korean Sea at latitude 39N and boldly steamed in a northerly direction to the farthest point we could. In so doing we had traversed Operation Areas Mars, Venus, and Pluto so named because like the planets, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is really far out. We knew that the lackeys of the Bowery Street Billionaires would never be satiated until we had found out all there was to know about the huge successes that the noble peace loving peoples of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea had made in the recent past. Surely we had to find out how come such a newly created government could lead its peoples so quickly into the number one position. As we went about detecting this valuable information, particularly the oceanic salinity, density, ionic dispersion rate, humpback whale counts, both low and high protoplasmic unicellular uglena and plankton counts. This information was of the highest value to our own scientists for the development of war mongering at sea when no one was looking.

Now we have come to realize just how great our crimes were and we seek the leniency of the Korean people even though we are criminals of the basest variety and deserve only swift punishment of the just Korean law. Further, we know that our crimes are greater than those of any criminals discovered this century, nevertheless we ask forgiveness and promise never to engage in such naughty acts ever again if we are forgiven. We know that our crime is merely a reflection of the dastardly policies of the Bowery Street Billionaires and we can only hope they will realize their own responsibilities for our actions; because who else could have dreamed up such a heinous and foul playing ship as Pueblo and then searched out enough arch criminals such as we to operate it. Yea, we feel it is time indeed for those really responsible for us to step forward and accept their own roles and admit, apologize, and give assurances that they will never again prepare another spy bag to be filled with goodies.

In summation, we who have been rotating upon the fickle finger of fate for such long languid months give our word to the Great Speckled Bird that we will hereto for in all sincerity cleanse ourselves of rottenness and vituperations. We solemnly await our return to our loved ones so that the fickle finger can be replaced by the rosy fingers of dawn and salvation. So help me, Hanna.

S/L.M. Bucher

Editor’s Note: Lieutenant Schumacher passed away on 16 May 2018. He was posthumously awarded Naval History author of the year for his article.

At the U.S. Naval Institute’s annual meeting on 25 April 2019, Lieutenant Schumacher’s family were invited to accept the award on his behalf. Watch their moving tribute below: