A leading aviation journal stated: “The A-12 attack bomber is emerging as the most important U.S. Navy aircraft programme of the present decade and seems likely to be the last all-new type to enter service with the Navy this century.”1 But as the magazine was coming off the press, on 7 January 1991, Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney ceased funding the A-12 Avenger program—the largest project termination in U.S. Defense Department history.

The A-12 had its origins as the Advanced Tactical Aircraft (ATA) program begun in 1983 to provide a long-range, low-observable attack aircraft to replace the Grumman A-6 Intruder in carrier air wings. Five years later, the team of McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics was selected to develop the ATA and to produce four flight test and eight full-scale development aircraft.

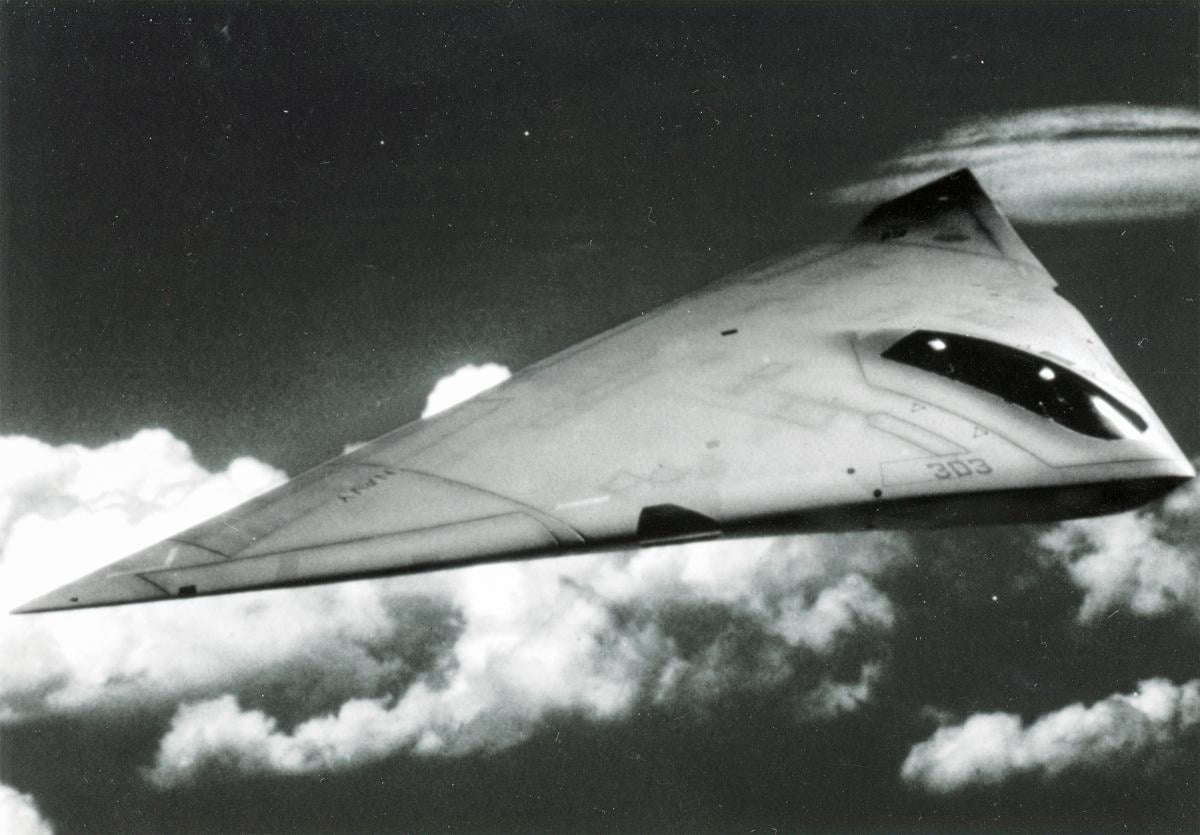

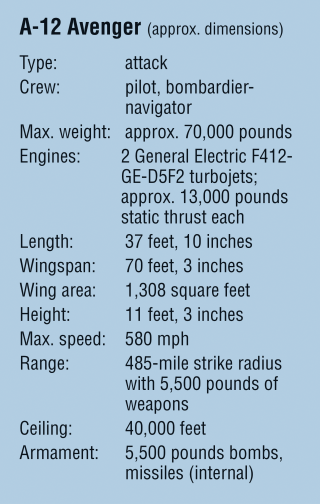

A flying-wing design, the A-12 had a relatively small fuselage and minimal tail surfaces, significantly reducing drag. Compared to the A-6E Intruder—which had joined the fleet in 1971—the A-12 was to have greater speed and altitude, an internal weapons bay to reduce drag, and a considerably smaller radar cross-section. Also, the A-12 was to be easier to support and maintain.

In the attack configuration, the A-12 was to have a two-man crew (as did the A-6 Intruder), and for “other missions”—presumably electronic warfare variants—the A-12 would have a three-man crew. The basic aircraft would have a dual-function radar/infrared search and tracking system, with the radar having both air-to-air and air-to-ground modes. (Antiship, close air support, and tanker missions also were envisioned for the basic aircraft.)

The A-12 would be a large aircraft, with wingspan limited by the requirement to fit two A-12s on adjacent catapults on a carrier flight deck. In addition, two A-12s with folded wings had to be accommodated on a deck-edge elevator.

Prospects for the A-12 were promising: The Navy planned to buy 620 aircraft and the Marine Corps another 238, with the first to enter service about 1995. At one point, the Air Force was reported to be considering a 400-plane buy; however, as with that service’s procurement of the Navy-developed F4H/F-4 Phantom and A-7 Corsair, it probably would have taken “outside” direction for the Air Force to acquire the aircraft.

As the A-12 was being developed, Vice Admiral Richard Dunleavy, the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (Air), on 5 March 1990, noted, “I like what I see and [it] will be a good airplane.”2 The cancellation of the planned A-6F variant of the Intruder seemed to further ensure the success of the A-12 effort. Also, the two other carrier aircraft then in production, the F-14 Tomcat and F/A-18 Hornet, were not suitable for the “medium” attack role, i.e., as an Intruder replacement. Indeed, a headline in Jane’s Defence Weekly in 1990 declared, “USN’s A-12 Avenger: in good shape for survival.”3

The shootdown came a short time later.

The aircraft—yet to fly—was not meeting specifications: It was overweight, and manufacturing was proving more difficult than anticipated. After seven years of research and development, and an expenditure of some $5 billion, the ATA/A-12 Avenger program was halted. Aviation historian James Stevenson’s excellent account of the program tells a tale of changes in leadership, objectives, and funding “that were bound to devastate the program.”4 But overarching was the byzantine procurement “system” Congress had imposed on the Pentagon and the Defense Department’s own self-imposed bureaucracy. At the time, the estimated unit cost for production aircraft was $96 million, and the program was over budget and some 18 months behind schedule.

With the end of the program, the government wanted the aircraft contractors to return some of the funding. McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics disputed the claim in federal court. The legal issues dragged on for more than a decade.

In the event, the A-12 was not built and there would be no successor to the highly regarded A-6 Intruder. The ubiquitous F/A-18 Hornet—in later variants—would become the U.S. Navy’s only carrier-based attack aircraft.

1. “General Dynamics/McDonnell Douglas A-12 Avenger,” Air International (January 1991), 51.

2. Vice Admiral Dunleavy served as DCNO (Air) from May 1989 to June 1992.

3. “USN’s A-12 Avenger: in good shape for survival,” Jane’s Defence Weekly (1 September 1990), 322.

4. James P. Stevenson, The $5 Billion Misunderstanding (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001), xii.