Few ships logged a career anything like that of the Bear. Over her 89 years—47 in commissioned U.S. service—she served as a sealer, was commissioned in the U.S. Navy three times over the span of 60 years, served the Treasury Department twice in the Revenue Cutter Service and Coast Guard, and was a museum ship, a “movie star,” and a civilian research vessel. In that timespan she gained worldwide attention twice, with one historian citing her as “probably the most famous ship in the history of the Coast Guard.” During World War II, she was the oldest U.S. Navy ship to be deployed outside the United States and was one of the very few to have served not only in World War I, but also in the Spanish-American War. Virtually her entire service was spent in Arctic or Antarctic waters.

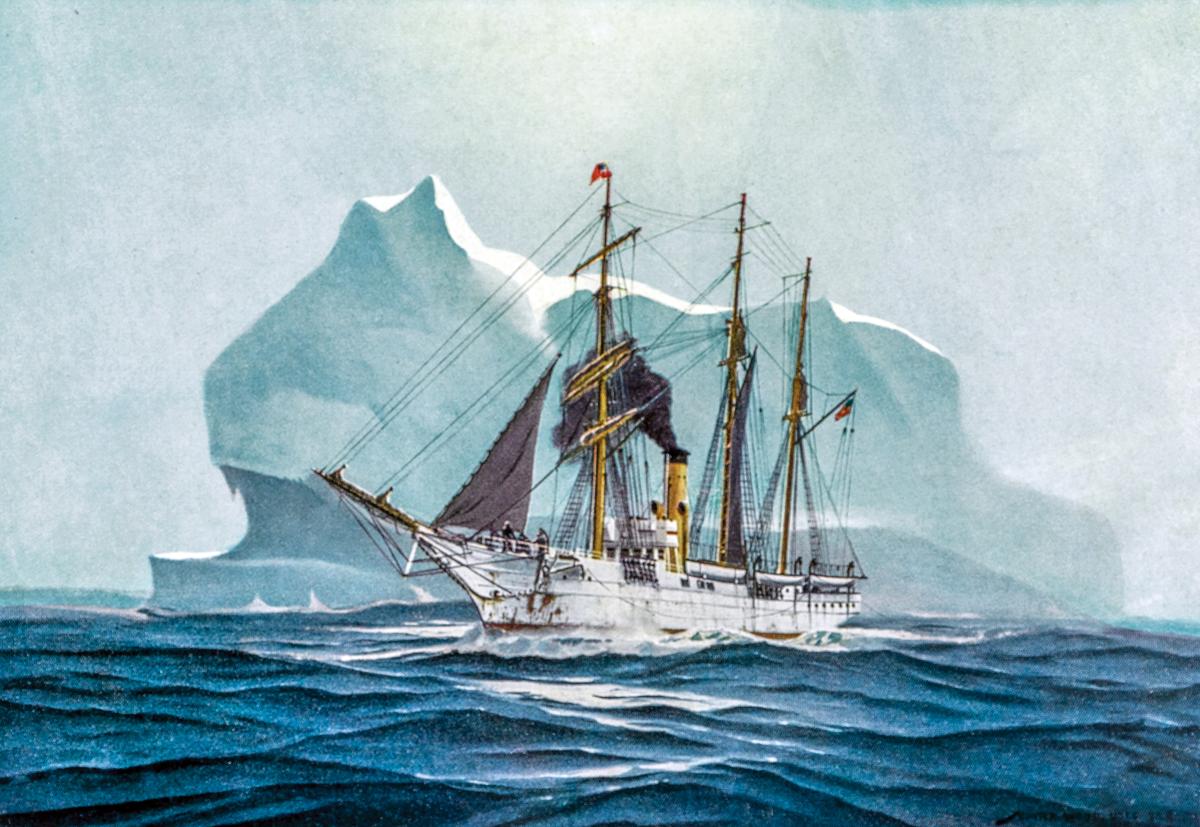

The barquentine-rigged steam cutter began her service life in 1874 on the east coast of Scotland in Dundee at Alexander Stephen & Sons Limited Yard No. 56. She was custom built for sealing, and steel plating at her bow reinforced her hull of six-inch-thick planks. Although rigged with sails, her 101-hp compound steam engine turning a single screw allowed her to punch through relatively thick ice (compared to other small schooner and barque sealers of the day) to reach her quarry.

The cutter spent her first decade in sealing operations out of St. John’s, Newfoundland, first with W. Grieve, Sons & Company until 1879, then with R. Steele Jr. After the ship’s refitting in 1884, the U.S. government acquired her specifically to participate in the search for the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, perhaps better known as the Greely Expedition. On 22 June 1881, the newly purchased Bear, along with three other ships, rescued the seven expedition survivors and garnered worldwide headlines.

Of no additional use to the Navy, the Bear was transferred in 1885 to the Treasury Department’s Revenue Cutter Service as part of the Alaskan Patrol. There, in the Arctic Ocean and waters around Alaska, the brigantine spent 41 years as one of the sole government representatives in the region. Because of this, her commander was to assume an outsize role and significance. Fortunately, her newly appointed captain was up to the task.

Michael Augustine Healy’s nickname said it all. “Hell Roaring Mike” was, according to a contemporary newspaper account, an “ideal commander of the old school, bluff, prompt, fearless, just.” In what appears to be a matter of course, over his nine years as ship’s commander, he introduced missions that the Revenue Cutter Service’s descendant, the Coast Guard, adopted as its stock-in-trade: protecting natural resources, suppressing illegal trade, resupplying remote outposts, and conducting search-and-rescue missions.

The Bear carried mail, which accumulated at Seattle during the winter, and transported government agents and supplies north and federal prisoners south. Her doctor served the needs of indigenous people and newcomers alike, and her deck often served as a court, meting out the only justice in the area. The cutter engaged in scientific inquiry and coastal surveys to improve charts and—in today’s vernacular—humanitarian-relief operations. Healy (whether it was his idea is open to debate) engaged with naturalist John Muir to introduce reindeer from Siberia into Alaska. The native populations were always on the edge of starvation, and Healy’s experience with Russia led him to believe reindeer would be not only a prime food source, but also a good supplier of clothing and transportation.

Captain Healy was not without his vices—chief among them being alcohol—but he knew himself best. “When I am in charge of a vessel, I always command; nobody commands but me. I take all the responsibility, all the risks, all the hardships that my office would call upon me to take. I do not steer by any man’s compass but my own.” He was court-martialed twice and lost command of the Bear in 1896. Healy retired from the service in 1903 and died the next year.

The Bear made headlines once again in 1897 with an epic overland rescue of 275 seamen on eight whalers trapped in pack ice off Point Barrow. At the cusp of winter on 14 December, the cutter had gone as far as she could go and still was some 1,600 miles from the victims. Before turning back, the Bear’s new commander, Francis Tuttle, landed a rescue party of dog teams, sleds, and guides to complete the rescue. The “Overland Expedition for the Relief of the Whalers in the Arctic Ocean” collected a herd of about 450 “Healys”—as the reindeer were known—as they pushed through the whole Arctic winter before reaching the stranded whalers three and a half months later in March 1898.

The next three decades were less exciting, as the Bear continued her work with the Alaskan Patrol. The Navy took her over for two years once the United States entered World War I in 1917 but had her continue her work in Alaska, as she did after being released to what was now known as the Coast Guard. On 3 May 1929, after 55 years of service, she was decommissioned and donated to the city of Oakland, California, for use as a museum ship. Almost immediately, she took a starring role in the fourth film adaptation of Jack London’s The Sea Wolf.

In 1931, Arctic explorer Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd, who was searching for an icebreaker for his Second Antarctic Expedition, negotiated the purchase of the Bear from Oakland for just $1,050, about $15,800 in 2018 dollars. After refitting, she was renamed Bear of Oakland before setting sail for Antarctica on 25 September. Unfortunately, she was damaged when she ran into a hurricane off Cape Hatteras, which forced her into Newport News, Virginia, for repairs. She finally arrived in the Bay of Whales on 30 January 1934 and served the expedition until 7 February 1935.

After discussions with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Byrd gave up plans for a private, third expedition to join the government’s U.S. Antarctic Service Expedition, 1939–41. Although the expedition was government sponsored, money still was scarce, and it depended on significant private funding and donations; Byrd himself donated the Bear of Oakland. The Navy leased the ship for $1 per year and had her refitted by removing her boiler and engine and inserting a diesel. She then was commissioned as the USS Bear (AG-29).

For this expedition, the Bear made two trips. On the first, from 22 November 1939 to 21 March 1940, she delivered an aircraft and supplies and served as a base for Byrd’s flights to scout and set up a second base at what became known as Stonington Island. With the worsening world situation, it was decided to evacuate the two Antarctic bases. The relief began on 13 October 1940 with the Bear’s departure from the United States, in company with the USMS North Star. They arrived at the Bay of Whales on 11 January 1941 and departed 22 March, with the Bear arriving in Boston on 18 May.

Shortly thereafter, the cutter received her war orders. She was assigned to the Northeast Greenland Patrol, where on 12 September, prior to U.S. entry into World War II, she and the Coast Guard cutters North Star (WPG-59) and Northland (WPG-49) were involved in the first capture of a belligerent ship by U.S. naval forces. The allegedly neutral Norwegian sealer Buskoe was under German control and supporting clandestine radio and weather stations in Greenland. The Bear towed the captured vessel along with her crew and passengers to Boston for internment. The remainder of her war was less exciting, and as more modern ships entered battle in greater numbers, she was decommissioned on 17 May 1944.

Her subsequent existence was all downhill. Laid up in Boston after being decommissioned, the Bear was sold in 1948 to Shaw Steamships of Canada, which was going to refit her for her original role as a sealer. This came to naught, and the cutter remained laid up. Plans for her use as a museum ship in Canada and again in Oakland also fell through. In 1962, Alfred M. Johnston purchased her for use as a museum and restaurant near Philadelphia. While under tow to her new home, the renamed Arctic Bear was struck by a gale that severed the towline and, worse, collapsed her foremast, which punctured her hull. She foundered on 19 March 1963 about 260 miles east of Boston.