On 18 February 1952, Captain Frederick Paetzel was not taking any chances with the storm that had overtaken his 503-foot oil tanker, the Fort Mercer. He kept the Mercer’s bow pointed into the rising seas, holding position, prepared to ride out the storm. Paetzel had guided the ship safely since leaving Norco, Louisiana, and now, just 30 miles southeast of Chatham, Massachusetts, he was closing in on his final destination of Portland, Maine. He might be delayed by the storm, but rough seas in the North Atlantic during February were not unexpected, and he would bide his time until the storm blew itself out.

The nor’easter, however, showed no signs of weakening, instead intensifying with each passing hour. By the time a pale hint of light indicated dawn’s arrival, waves had grown to 50 and 60 feet and the wind approached hurricane strength, hurling a freezing mix of sleet and snow at the vessel. The Mercer took a terrible pounding, yet she rode the seas as well as could be expected.

But at 0800, Captain Paetzel heard a sharp crack echo from the innards of his ship. He wasn’t immediately sure what had happened, but he and several crew members soon saw oil spewing over the ocean from the starboard side of the Mercer, and they knew her hull had cracked.

The 48-year-old captain immediately slowed the vessel’s speed by a third and positioned the ship so the waves were on the port bow, to keep the fracture from growing. After alerting the rest of his crew, he radioed the U.S. Coast Guard for assistance, reporting that his ship’s seams had opened up in the vicinity of the number five cargo tank and her load of fuel was bleeding into the sea.

Then Paetzel and his crew of 42 men prayed their ship would stay together until Coast Guard cutters arrived. The German-born captain had been at sea since he was 14, but he’d never seen a storm like the one in which he was caught, nor had he ever heard the sickening crack of metal giving way to the sea.

Approximately 150 miles away on board the Coast Guard Cutter Eastwind (WAGB-279), radio operator Len Whitmore was doing his best to ignore the rolling motion of the ship and focus on the radio when he heard the distress call from Captain Paetzel. He alerted his captain, and immediately the Eastwind started steaming toward the crippled tanker. “The weather was blowing a whole gale and the seas were enormous,” recalled Whitmore,

“. . . a lot of our crew was sea-sick, but still working. With those seas I thought it might take us a whole day to get to the Mercer, and by then it might be too late.”

Another Coast Guard vessel, the Unimak (WAVP-379), which was south of Nantucket searching for the fishing vessel Paolina, was diverted from that search and started pounding her way through the storm toward the Mercer. In Provincetown, Massachusetts, the cutter Yakutat (WAVP-380) was dispatched to the scene, as was the McCulloch (WAVP-386) out of Boston.

On board the Fort Mercer, Captain Paetzel tensed each time a particularly large wind-whipped wave hit the vessel. Oil continued to stain the ocean, and the ship’s quartermaster did his best to keep the bow into the oncoming seas. Paetzel had the crew don life vests, but beyond that safety measure, they could do little but wait for the Coast Guard to arrive.

Remarkably, at 1000, The Boston Globe was able to make a shore-to-ship telephone connection with the captain. Paetzel said conditions were very rough and that waves had reached 68 feet, rising up into the rigging, but he believed his ship “did not appear in any immediate danger.” However, he also acknowledged he could not be sure of the situation because surveying the damage more closely from the deck would be suicidal. “We’re just standing still,” he added. As a final thought, he considered loved ones on shore and expressed a hope that “none of our wives hear about this.” The Mercer was not listing, and since the earlier sound of metal splitting there had been no more serious events. The captain remained hopeful that the worst was behind them.

While Paetzel may have thought the Mercer was not in immediate jeopardy, he also knew the history of the partly prefabricated and welded T-2 tankers, and that knowledge was not comforting. At that time, eight of the tankers had been lost due to hull fractures, and the T-2s were particularly susceptible to cracking when large seas were accompanied by cold temperatures—the exact situation in which the Mercer now found herself. The captain would breathe easier when the Coast Guard cutters were within sight.

Suddenly, at 1030, another terrifying crack rang out, and the ship lurched. Paetzel instantly sent another message to the Coast Guard explaining the situation was worsening. A cold dread coursed through the captain; he knew his ship might become the ninth T-2 tanker to be taken by the sea.

Another long hour went by without incident. Then at 1140, a third loud report was heard as more metal cracked. Paetzel now could see the crack, extending from the starboard side number five cargo tank to several feet above the waterline, with oil spurting into the seas. At 1158 Paetzel had another SOS sent, this one accompanied by the message, “Our hull is splitting.”

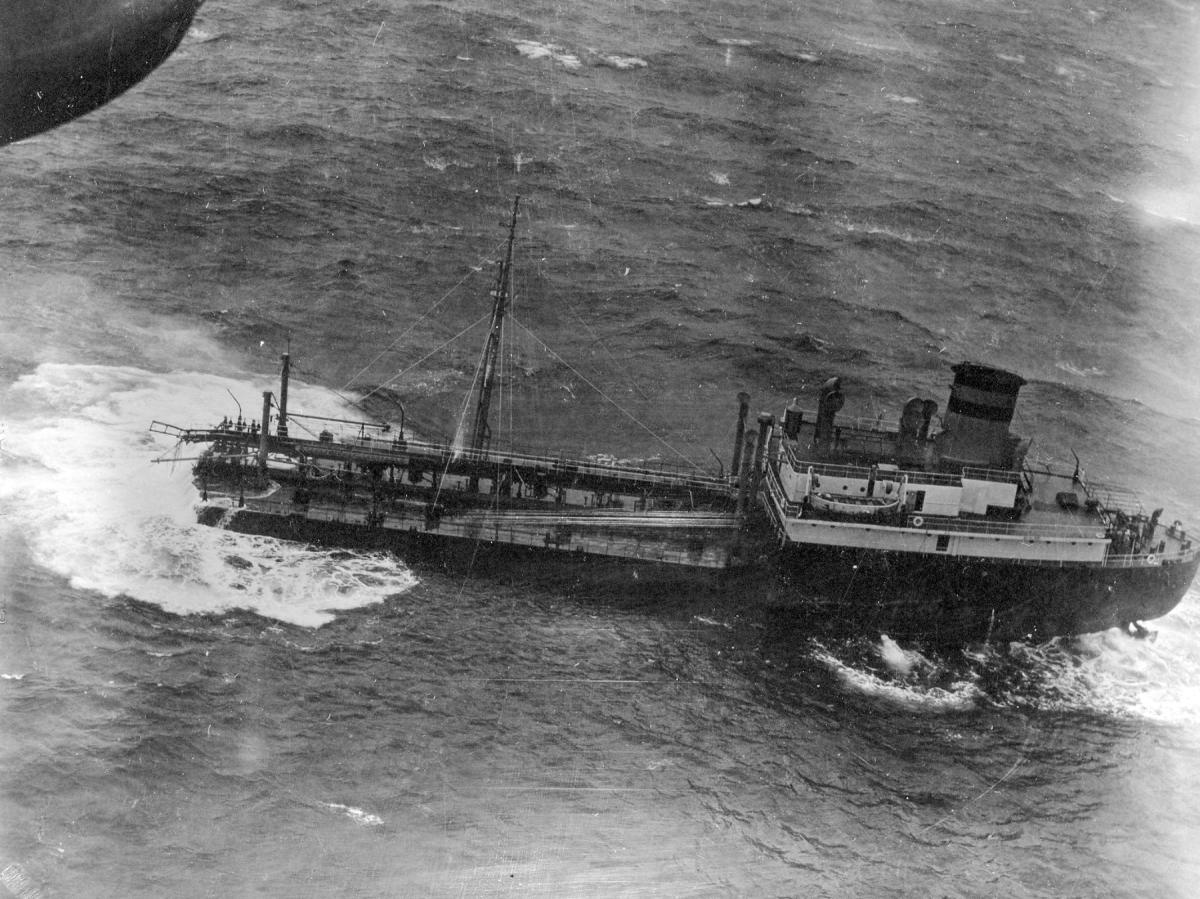

A few minutes later a wave smashed the tanker so hard crewmen were thrown to the deck. When they got to their feet they could not believe what they saw; the vessel had split in two.

Crew member Alanson Winn remembered that when the final crack and split occurred it was so loud and violent he thought the ship had been rammed. “Then she lifted up out of the water like an elevator. She gave two jumps. And when she’d done that she tore away,” he recalled.

Captain Paetzel was trapped on the bow with eight other men, while the stern held 34 crew members, and each end was drifting away from the other. Seas tossed the bow wildly about, first swinging it sharply to starboard. The forward end of the bow rode high in the air, but the aft section sloped down to the sea, submerging a portion of the deck and washing away the lifeboats. Equally as devastating, the accident had knocked out the radio, and Paetzel no longer could work with the Coast Guard for rescue, nor could he offer instructions to the crew members on the stern. He and his men were trapped in the bridge—to leave might mean instant death. The bow wallowed in the monstrous seas, and without engine power it was broadside to the waves, taking direct hits.

The stern section, where the engine was located, was in better shape, and all of it was above the seas. Immediately after the split, engineers had shut down the engine, but now the crew on the stern could see waves pushing the bow back toward them like a battering ram. Miraculously, the engineers were able to restart the engine. They put the propeller in reverse and were able to back the stern away before the bow ran them down.

Through the long afternoon, Captain Paetzel and the men trapped in the bow huddled in the unheated chart room. Just after nightfall, the cutter Yakutat arrived at the scene, but the waves were too large for her to pull alongside for a rescue, so she hovered nearby, waiting for the wind and waves to ease.

Paetzel and crew, however, were becoming desperate. The front of the bow section was sticking completely out of the water, but the aft section of the hulk, where Paetzel and crew were trapped in the chart room, was sinking lower into the sea. They were without lights or other means to signal back to the Yakutat, and slowly the room was filling with water. Just before midnight they decided to try to move to the forecastle room, where they hoped to escape the rising water and find signaling equipment. To do so, however, meant first lowering themselves out of the chart room and on to the exposed deck, which was awash with spray, snow, and sometimes the sea itself.

The door from the chart room to the deck was too close to the sinking end of the hulk, and the drop from a porthole to the deck was too great to risk jumping. So the crew improvised, tying various signal flags together to create a line, which they lowered out the porthole on the forward side of the chart room. One by one, the men started out, first lowering themselves down the signal flag line, then taking the most harrowing footsteps of their lives as they headed forward on the icy, upward-sloping catwalk.

The ship pitched and rolled, and the men ran toward the forecastle as white water surged around their feet. Radio operator John O’Reilly, who had transmitted the May Day earlier that morning, lost his footing and was swept overboard, disappearing into the churning abyss. The other eight crew members—including Captain Paetzel, who had been caught in his slippers when the tanker split and made the crossing barefoot—reached the forecastle safely.

Commander Joseph Naab on board the Yakutat had seen the men run across the catwalk, and he knew the tanker crewmen were desperate enough to do anything. He decided he had better make an attempt to get them off. He maneuvered the cutter windward of the tanker, and his men tied several life rafts in a row, dropped them overboard, and let the wind carry them toward the tanker. Lights and life jackets were attached to each of the life rafts.

On the Mercer’s bow, the survivors watched the rafts coming toward them. It was decision time, and what an awful decision it was. Each man had to make a choice in the next minute that might mean the difference between life and death. There was no one to give them guidance, assurance, or even the odds they faced. If they stayed with the fractured ship, they risked her rolling over at any moment, taking them down with her, trapping them in the freezing black water below. But to jump from the ship held its own perils, not the least of which was the possibility they would not land inside the raft. Maybe they would have the strength to swim to the raft and haul themselves up and in, or maybe the frigid seas would so weaken them that they would never make it to the side of the raft, let alone climb aboard.

Three crew members believed the rafts were their best chance of escaping the storm alive. They crawled to the side of the deck and, one by one, threw themselves overboard and down toward the rafts. All three missed. The shock of the freezing water made swimming nearly impossible, and although they tried to get to the rafts, the mountainous seas buried them and they disappeared from view. Commander Naab watched in horror as the men were swallowed by the seas.

One of the tanker crewmen, Jerome Higgins, still on board the Mercer, saw how close the Yakutat was and made a fatal choice. He leaped over the rail, hit the water, and tried to swim to the cutter. In the howling darkness the seas swept him away, and in a flash he was gone. Naab, not wanting to witness any more drowning, backed the cutter away and lay off, now knowing a nighttime rescue attempt would be suicidal for the tanker crew. He decided the best option was to wait for dawn.

The decision proved to be a good one, because the next day all four remaining survivors were rescued by the Yakutat’s small motor lifeboats and more rafts. Just minutes after the last survivor was safely hauled aboard the cutter, the Fort Mercer’s bow reared up in the air, crashed backward, and sank.

Commander Naab was lauded for his leadership and skill during the rescue, but he was haunted by the deaths of the crewmen who didn’t make it. He would later say that watching the men jump from the ship and be taken by the sea was “the worst hour of my life.”