While a key role of the present-day U.S. Coast Guard is drug interdiction, the same was true of one of its predecessor agencies—the U.S. Revenue Marine Service—in Pacific Northwest waters during the late 19th century. At mid-morning on 14 January 1886, the U.S. Revenue Cutter Oliver Wolcott won a 736-mile, intelligence-driven race through inland waterways, freezing temperatures, and a raging gale to seize more than 3,000 pounds of refined opium before it could be smuggled by sea to the U.S. mainland.

A Drug and an Industry

The maritime smuggling of opium from southwestern Canada into the American Pacific Northwest had mushroomed in the 1880s. This upturn followed the negotiation of treaties and enactment of legislation restricting the entry of Chinese nationals into the United States and, in an effort to curb the spreading practice of smoking the drug, imposing an exorbitant duty on the legal import of opium. The first measure was an 1880 treaty; China would prevent its citizens in America from importing opium from China, and the United States would do the same with respect to China. However, the treaty initially lacked implementing U.S. legislation and did little to lessen the influx of refined opium.

Then in 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which outlawed the entry into the United States of any Chinese person who would be engaged in labor. This significantly restricted the mobility of Chinese, since those seeking to reenter the United States would need to prove they had means of support and were not seeking to work in the country. One of its effects was to limit opium smuggling to Americans; the increased border scrutiny Chinese faced made it impractical for them to be smugglers.

The legislation that most directly fueled the increase in opium smuggling was the Tariff Law of 1883. It banned outright the U.S. import of raw opium that contained less than 9 percent morphia. This type could be processed into refined, or “smoking,” opium. As for the import of refined opium, the law imposed a stiff tariff of $10 per pound. The duty on raw opium containing more than 9 percent morphia, which was used in the manufacture of pharmaceutical products, remained $1 per pound. The law drove Chinese opium manufacturers to set up refining operations in ports along the southwest coast of Canada, where raw opium could still be imported legally and customers in America were in convenient proximity. The U.S. duty of $10 per pound on a product that retailed for $6 to $10 per pound, depending on quality, ensured the profitability of opium smuggling.

The bustling port of Victoria, British Columbia, on the southeastern tip of Vancouver Island and barely more than 35 miles from Port Townsend, Washington Territory, became the opium industry’s leading city in North America. By 1884 it was home to six Chinese-owned factories where raw opium was refined into smoking opium and packaged in tins, or cans, for distribution; by 1887 13 factories in Victoria were producing more than 90,000 pounds of the drug per year. Each tin contained six and a half ounces of opium, which the U.S. Customs Service usually calculated as a half-pound. Along Victoria’s waterfront, confidential informants, seeking to hurt rival manufacturers or gain a monetary reward, and U.S. Customs Service agents sought out intelligence that frequently led to seizures of illegal opium shipments.

Smugglers used several methods to move the drug from Canada into the United States, including merchant steamships, private vessels, and, to reach crossings farther inland, the Canadian Pacific Railroad. Small loads of 10 to 50 pounds were carried by smugglers posing as passengers or were transported on board small fishing sloops or other private vessels bound for Washington’s San Juan Islands and the area around Port Townsend. Larger loads of up to several hundred pounds were typically concealed on board commercial steamers, the opium usually being moved “on commission” for a few dollars per pound by complicit ship officers or crewmen. The risk to the smugglers was low. Few culprits were identified and fewer vessels were seized because the owners or captains rarely were involved. Even if authorities confiscated a shipment, the producer did not face a total loss; some of the value of the seized opium could be recouped by retaining an agent to purchase the confiscated drug at its subsequent auction, usually at a discount to retail, and then having it delivered to the originally intended customer.

On the Trail of Smugglers

To combat this smuggling, cutters of the Revenue Marine Service—as the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service was then known—and local customs collectors cooperated very closely. The cutters frequently provided manpower to assist customs inspectors with pierside searches, while the inspectors in turn often passed actionable intelligence to the cutters and participated with cuttermen in at-sea boardings of suspected smugglers’ vessels. Almost all of the intelligence was gathered in Victoria.

The port was rife with informants and U.S. customs detectives. Opium factory owners seeking to gain market share or with an ax to grind snitched on rivals by revealing the details of their planned shipments. Confidential informants volunteered information in anticipation of financial reward (they could be paid up to 25 percent of the proceeds from subsequent auction of opium seized on the basis of their information). Additionally, U.S. Customs agents prowled the city, listening for tips and watching for evidence of Port Townsend–bound vessels taking aboard opium. All of these elements would be exploited in the case of the steamer SS Idaho.

In November 1885, a confidential informant slipped into the U.S. Consulate in Victoria and passed information that Captain James Carroll of the Idaho routinely picked up a load of opium on the Alaska-bound leg of his route, which he then kept concealed on board his vessel until he offloaded it at Port Townsend on his return trip south. He escaped scrutiny because he never loaded contraband in Victoria just prior to departing for Port Townsend. The informant also gave the specific intelligence that on her next trip the Idaho would be taking aboard around 3,600 pounds of opium from the Tai Yuen opium factory in half-pound tins that would be concealed in 14 barrels.

When this information was telegraphed to Collector of Customs Herbert Beecher in Port Townsend, he sent Inspector Edwin Gardner and another detective to investigate. They set up surveillance of both the factory and the Idaho on her arrival in Victoria. Not only did they observe a meeting between Captain Carroll and the owner of an opium refinery, the detectives watched as a wagon from the factory made an unscheduled, after-sunset delivery—the size of which fit the informant’s description—to the Idaho.

Armed with this intelligence, Collector Beecher, Inspector Gardner, and a detail of three officers and ten enlisted men from the U.S. Revenue Cutter Oliver Wolcott were waiting at the pier when the Idaho pulled into Port Townsend on her return from the northbound leg of her route the afternoon of 26 December.

The first day’s search of the vessel ended around 2300, yielding only 30 pounds of opium. The next day, after the Chinese cook had been observed disembarking from and then boarding the vessel several times, he was stopped while going ashore and searched by a customs agent who found several tins of opium hidden in his clothing. Over the next few days, subsequent searches of the Idaho’s cabins, holds, and cargo discovered around 600 pounds of opium in tins. A large amount was hidden behind a false washstand, but none was discovered in barrels. The ship’s carpenter had been arrested along with the cook, but Beecher could find no evidence that Carroll or the Idaho’s owners were involved. Reluctantly, he agreed to allow the steamer to proceed on New Year’s Day to Portland, Oregon, where she was to unload 300 tons of coal. He sent four of his customs agents with the vessel to oversee the offload in the chance that the remaining opium was hidden in the coal.

Still perplexed by the large discrepancy between the amount of opium predicted in the intelligence report and the amount discovered, Beecher hired a “submarine diver” to examine the sea floor for tins that might have been jettisoned to avoid discovery. This also proved fruitless, although several interesting relics were found.

On 9 January 1886, the Idaho, on the northbound leg of her route, returned to Port Townsend. Once finished there, she would make the short trip over to Victoria before continuing on to Alaska. The investigation of her appeared to be at an end. However, during the Port Townsend stop a seemingly routine personnel decision would result in the unraveling of the Idaho’s large-scale smuggling operation.

Big Break in the Case

About ten days earlier, Henry Hanson, an Idaho seaman, had somehow missed recall for the steamer’s departure from Port Townsend after customs officials had finished searching her. When he realized the ship had left for Portland without him, Hanson took a room, confident in the knowledge that the Idaho would be back in week or so—at which point he would simply rejoin the vessel. However, when he tried to board the Idaho on her return to Port Townsend, he was coldly told that his services were no longer required and discharged.

Outraged, Hanson promptly marched over to the Customs House and relayed some astonishing information to Inspector Gardner. He had seen 14 barrels that he believed contained opium offloaded from the Idaho at the Kasaan Bay (Alaska) Salmon Fishery on her last trip north. He could identify the barrels and show Gardner where they were stored.

Beecher immediately sprang into action. Because the Idaho had already departed Port Townsend and there was no telegraph connection to the Customs House in Alaska, it would fall on him and the Wolcott to reach Kasaan Bay before the Idaho arrived and the evidence was removed. However, this was much more than a simple request for assistance with a dockside boarding or for the intercept of a vessel within the Wolcott’s assigned area of operations, which Captain James. B. Moore—the cutter’s commanding officer—could grant on his own authority. This trip would require the cutter to steam more than 690 miles at best speed and take her well beyond her normal operating area. Accordingly, Beecher telegraphed a formal request for assistance from the Wolcott to the Revenue Marine in Washington, D.C. He received prompt approval, but the cutter was under way patrolling Puget Sound.

Luckily, the Wolcott returned and dropped anchor in the harbor at 0920 the next day. Literally within ten minutes, Collector Beecher went aboard to deliver the telegram to Moore. Beecher shortly departed to collect Hansen and the supplies and equipment needed for a week-long deployment. Beecher also saw to it that Hansen’s lodging expenses were paid and agreed to take him in service—probably to pay him a salary for the time he would be needed

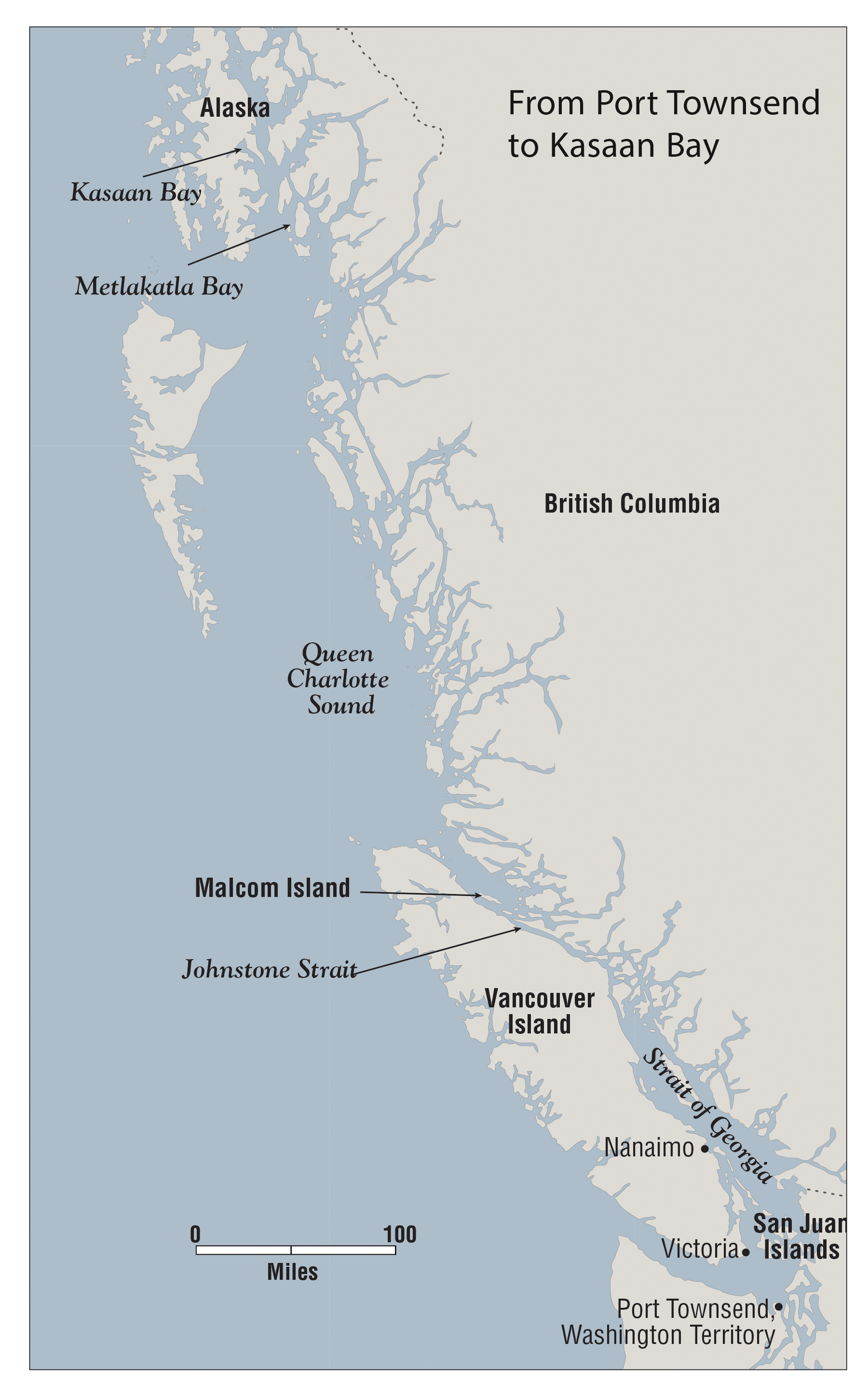

Early that afternoon, Beecher returned with Hansen, and the cutter promptly got under way. A little less than three and a half hours later, the Wolcott pulled into Victoria and learned the Idaho was still there. Beecher and Moore went ashore and found Robert Hicks, an experienced pilot, whose local knowledge and skills would enable the Wolcott to take the more direct inland passage east of Vancouver Island, rather than having to swing wide to the west before heading north to Alaska. This would save a lot of time but would entail 15 hours of travel through restricted waters, mostly at night, requiring the cutter to rely solely on steam power.

Race to Alaska

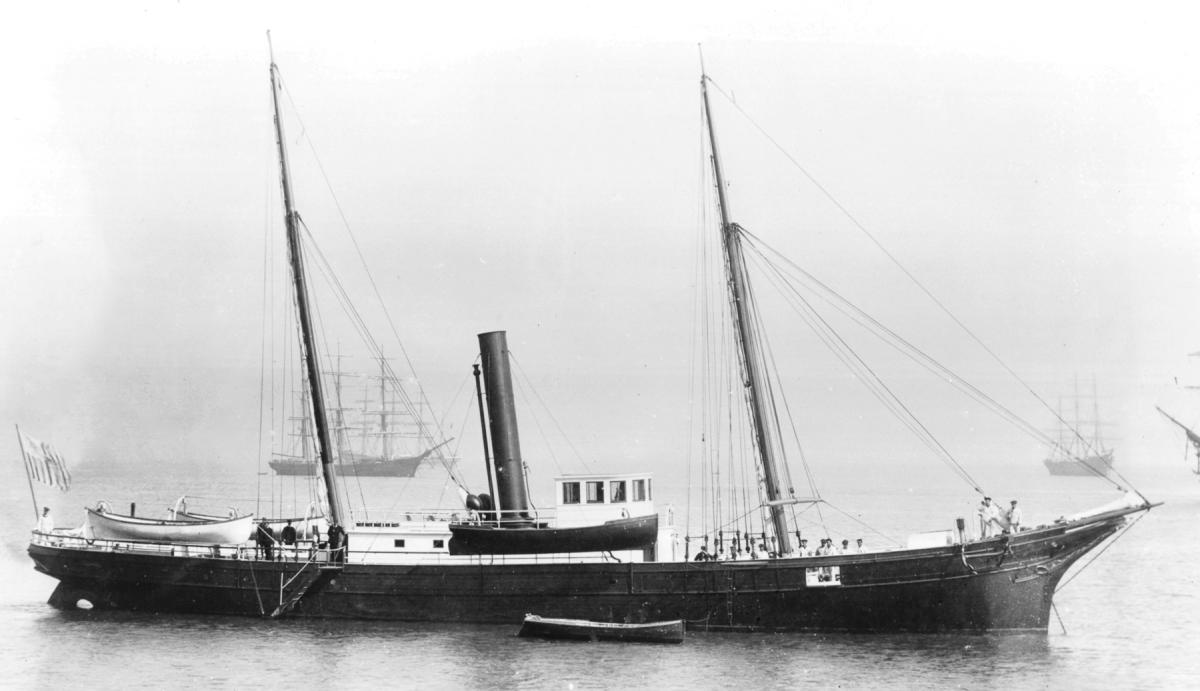

The Wolcott was a 155-foot sail-steamer with a draft of 9 feet, 7 inches. Although she could make nearly nine knots with favorable winds and seas and maybe a half-knot more when powered by her vertical-cylinder, surface-condensing steam engine, Captain Moore could not trust the vagaries of the wind to beat the Idaho. Winning the race would require several days of hard steaming, and the cutter’s logs would show that she burned just over eight tons of coal per day during that period. With less than 35 tons on board when the Wolcott departed Port Townsend, Moore would need to take on more. Fortunately, he could do so the next day in Nanaimo, which lay along the chosen route.

Shortly after loading 38 tons of coal there, the cutter began the race in earnest, passing through the narrow confines of the Strait of Georgia and Johnstone Strait. Although at times slowing to around seven and a half knots due to the confines of the channel, Moore proceeded most of the time at full speed. Much of the night had been overcast and raining, with moderate winds, but the sky cleared and winds abated when the Wolcott “passed the west end of Malcolm Island and stood into Queen Charlotte Sound” at 0500 on the morning of 12 January.The longest stretch of restricted waters was safely behind her.

By early afternoon, the rain returned and stayed until evening. The cutter continued to steam just offshore at full speed all day and into the night, with light and variable winds and a little fog appearing as the temperature rose into the low 50s. Sometime after midnight the temperature dropped, a heavy snow began to fall, and the wind picked up to 11 to 16 knots from the northwest. Before 0300 the snow had stopped, but the winds were still rising. By late morning the cutter found herself pressing into a full-blown gale. Three hours later, only about 115 miles short of his goal, Moore decided to seek respite from the still-strengthening winds and rising seas that slowed his cutter’s advance.

He diverted to Metlakatla Bay, where he anchored in seven and a half fathoms of water. Gale-force winds howled through the cutter’s rigging while she swung on 20 fathoms of chain for the next eight hours. When the winds had subsided slightly, Moore weighed anchor and the cutter pressed on through the night.

At 0800 the next morning, the Wolcott passed Grindall Island to starboard and entered Kasaan Bay. By this time the wind had calmed and the sky had cleared, but Moore encountered a new challenge: ice. Although not mentioned in the cutter’s log, newspaper accounts of the Wolcott’s exploit relate that parts of the bay were iced over and others were dotted with ice floes. Moore chose to anchor off the salmon fishery at mid-morning, sending Lieutenant Rhodes, Beecher, and six other men ashore by boat.

Once there, they learned that the fishery’s manager had departed to meet the Idaho at another Alaskan port. The two employees present accompanied the party as it made its way along the wharf to the building where Hanson remembered seeing the suspected barrels stored. The fishery’s employees assured Rhodes and Beecher that the barrels contained furs, just as they were marked, but when Rhodes opened the first one he quickly found tins of opium concealed in burlap bags. As Hansen had claimed, 14 such barrels were discovered. Rhodes signaled the cutter, which managed to work alongside the pier to take aboard the contraband.

A Record Haul

After initially dodging ice floes on her way out of the bay, the Wolcott enjoyed fair winds and favorable seas for most of her four-day return trip to Port Townsend. The cutter used sail power to conserve coal, still making nearly nine knots. The crew was also employed in examining the contents of the 14 barrels. After two days, the final count totaled 3,011½ pounds of refined opium. On the morning of 18 January, exactly eight days after Collector Beecher had delivered the cutter’s sailing orders, the Wolcott moored at Port Townsend to offload the contraband.

The total of 3,600 pounds of opium confiscated during the case brought in $45,000 when auctioned on 20 April by the U.S. Marshal’s Service. This was the first seizure of opium by a U.S. revenue cutter and at the time the largest seizure of the drug in U.S. history, both in terms of amount of opium captured and in value of cargo forfeited. As a result of his further investigation, Beecher was able to present sufficient evidence that the U.S. District Court ordered the Idaho forfeited in December. However, Beecher was unable obtain an indictment of James Carroll. He continued serving as a steamship captain, and after her owners posted a $30,000 bond against $132,000 in total fines and penalties, the Idaho returned to service until she ran aground in fog on Rosedale Reef in the Strait of Juan de Fuca in November 1889. The Oliver Wolcott and the handful of revenue cutters on the West Coast continued to seize opium at sea and to assist the Customs Service during the decades-long maritime campaign against opium smuggling.

Sources:

“Biggest Opium Seizure on Record,” Daily British Colonist (Victoria, British Columbia), 20 January 1886, http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist18860120uvic/18860120#page/n1/mode/1up.

“A Brilliant Seizure,” Daily Alta California, 19 January 1886, http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=DAC18860119.2.62.2&srpos=6&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-revenue+cutter+wolcott+opium------#.

“Ethnic Relations and the Transnational Connections of the Opium War in Pacific Canada, 1863–1937,” Canadian Defense and Security, 22 June 2012, https://sockshistory.wordpress.com/2012/06/22/hello-world/.

“The Idaho,” Daily British Colonist, 8 January 1886, http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist18860108uvic/18860108#page/n0/mode/1up.

“The “Idaho” Forfeited to the Government for Illegal Trading,” Daily Alta California, 8 December 1886, http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=DAC18861208.2.54.4#

“The Idaho’s Opium,” Daily British Colonist, 19 January 1886, http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist18860119uvic/18860119#page/n2/mode/1up.

“The Idaho in Trouble at Port Townsend,” Daily British Colonist, 30 December 1885, http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist18851230uvic/18851230#page/n2/mode/1up.

David Chuenyan Lai, Chinatowns: Towns within Cities in Canada (Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 1988).

Logs of the USRC Oliver J. Wolcott, 26 December 1885, 10–18 January 1886, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

James G. McCurdy, “Criss-Cross Over the Boundary,” Pacific Monthly, vol. 23, no. 1 (January 1910), 182–93.

“The Opium Seizure,” Daily British Colonist, 6 January 1886, http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist18860106uvic/18860106#page/n1/mode/1up.

“The Opium Seizure,” Daily British Colonist, 22 April 1886, http://archive.org/stream/dailycolonist18860422uvic/18860422#page/n2/mode/1up.

U.S. v. Steamship Idaho, Territory of Washington, Third Judicial District, no. 4799. Decided 3 December 1886, Office of the Secretary of State, Division of Archives and Record Management, Puget Sound Regional Branch.

E. W. Wright, ed., Marine History of the Pacific Northwest (Portland, OR: Lewis and Dreyden Printing Company, 1895).