African-Americans comprise the longest-serving minority group in the 225-year history of the U.S. Coast Guard and its predecessor services. However, after decades of incremental increases in African-American participation, it took an event of monumental proportions—World War II—to speed up the desegregation of the service.

In the decades leading to World War II, the number of African-Americans in the Coast Guard actually decreased because of a culture of discrimination against blacks. Despite their decline in overall numbers, African-Americans still experienced a number of advances prior to the war. Established as an all-black facility in 1880, North Carolina’s Pea Island Lifesaving Station stood as a symbol of African-American service in the predominantly white Coast Guard. In addition, the African-American Berry family had more than 20 members serve in the Coast Guard, beginning with the U.S. Lifesaving Service in 1897. And U.S. Lighthouse Service lightships experienced a greater degree of integration than ever before, with some lightships employing more than 50 percent minority crew members.

The Coast Guard also boasted of having the 20th century’s first desegregated federal vessel. From 1919 to 1925, the service stationed paddle-wheel cutters on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers to provide assistance during seasonal floods. The cutter Yocona, stationed at Vicksburg, Mississippi, was a diversity highlight of the interwar period. While her officers and noncommissioned officers were white, the cutter’s enlisted crew was African-American.

The Yocona may be considered the first integrated ship in modern U.S. history, but the service never recognized the cutter as an experiment in desegregation. Most likely, the Coast Guard recruited the best watermen in the Vicksburg area without intending the cutter to serve as an example of racial integration. Later, in World War II, the U.S. Navy’s first desegregated ships employed the same system of white officers and NCOs, with black enlisted men. However, the war’s integrated Coast Guard cutters included African-Americans in both senior enlisted and officer ranks.

Also during the interwar years, a black Coast Guardsman began his color barrier–breaking career in the service. Born in 1903, Clarence L. Samuels grew up in the Panama Canal Zone and in 1920 enlisted on board the Coast Guard cutter Earp, which was cruising in Panamanian waters at the time. Even though he grew up in Central America, the Coast Guard still categorized Samuels and other Afro-Caribbean recruits as African-Americans. In 1928 Boatswain’s Mate First Class Samuels assumed command of the 67-foot harbor vessel AB-15, becoming the first minority enlisted man to command an official U.S. ship of any kind. Samuels predated the Navy’s first African-American ship captain by almost 35 years.

1942–43: Years of Changes

The United States entered World War II in late 1941, and changes in minority enlistment began to take effect in 1942. Early that year, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for volunteer enlistments, including by minorities. By May the Coast Guard had opened all enlisted rates to minorities, and in June Congress passed legislation allowing the service to stand-up a “temporary reserve” corps of uniformed volunteers. This volunteer force supplemented the Coast Guard’s active-duty ranks, so more regulars and reservists could serve afloat and overseas. As a result, some African-American service members received temporary reserve enlisted rates.

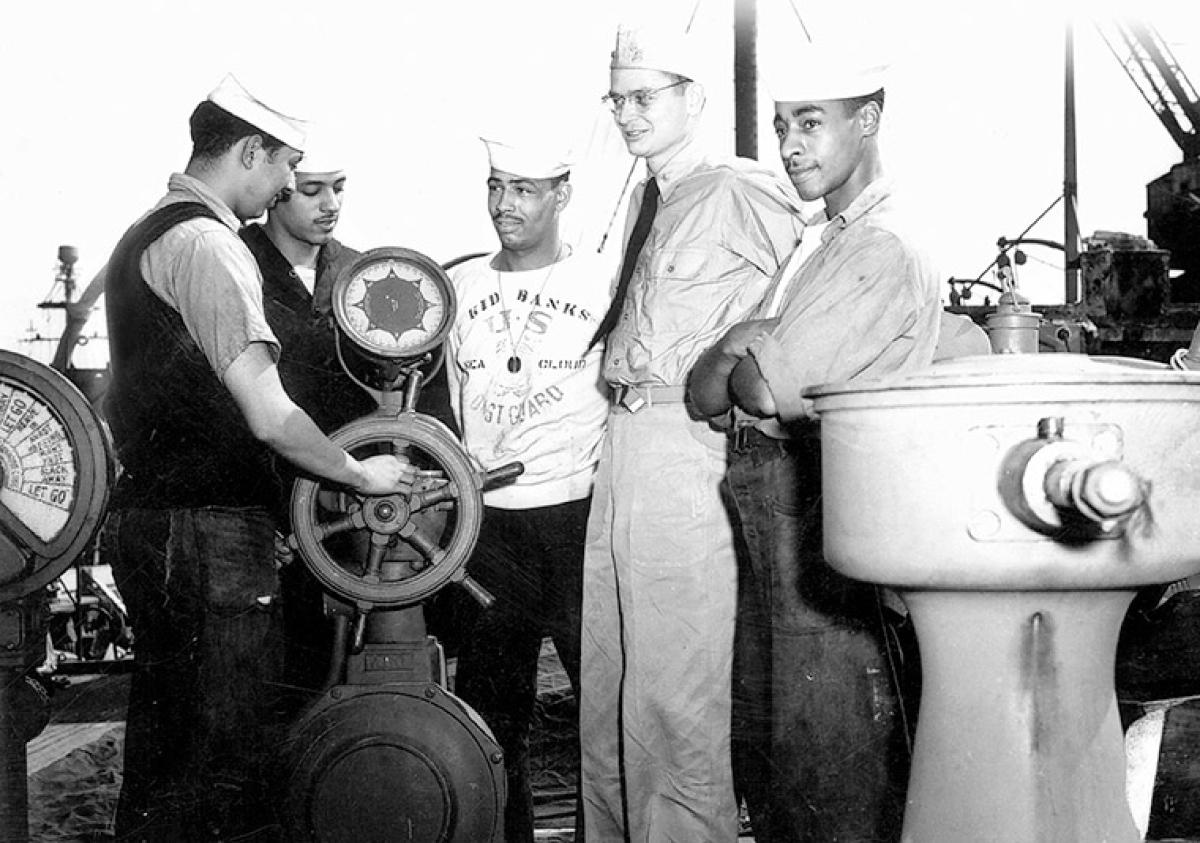

President Roosevelt’s call for enlistments brought in the first 150 African-American volunteers in March. They received training in all-black units alongside white units at the Coast Guard’s Manhattan Beach Training Center in New York City. Contemporary U.S. Navy facilities trained African-American units at separate training facilities. Initially, the Coast Guard assigned the black recruits to traditional minority shipboard positions in food-service and other subordinate rates. But many of the first African-Americans received shore duty, such as at the Tiana Beach Lifesaving Station on Long Island. This station boasted an all-black lifesaving and beach-patrol crew similar to the Pea Island Lifesaving Station’s.

On 1 September, the service advanced African-Americans Clarence Samuels and Joseph C. Jenkins to warrant-officer rank, making them its first minority members to reach that position. By December the federal government had instituted a general draft that included specific racial quotas. The Coast Guard inducted only about 15,000 men through this program, but an unprecedented 13 percent of the recruits were African-Americans.

In 1943 African-Americans continued to break Coast Guard color barriers. On 13 April, Joseph Jenkins graduated from Reserve Officer Training School, now known as Officer Candidate School, located at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy. He became the first commissioned U.S. sea service officer of African-American ancestry since the mid-1800s, when Revenue Cutter Service officer Michael Healy received a commission from President Abraham Lincoln. Healy rose through the officer ranks, but he had a very light complexion and never disclosed his race to others, so his background remained unknown to his peers and crews. On the other hand, Jenkins’ shipmates recognized him as an African-American officer.

On 31 August, a second African-American joined Jenkins as a commissioned officer when Clarence Samuels was appointed lieutenant (junior grade). Navy officials arguing in favor of integrating their own officer ranks took notice, and that sea service would commission its first black officers in 1944.

Experiments in Integration

White Coast Guard Lieutenant Carlton Skinner provided the impetus for a major step forward in desegregation when he submitted a proposal to the service’s commandant, Vice Admiral Russell R. Waesche, calling for shipboard integration. He argued that integration was in the best interest of “military and naval effectiveness.” In December 1943, the Coast Guard–manned Sea Cloud (IX-99), with Lieutenant Commander Skinner in command, became the federal government’s first deliberate test of desegregation on board a U.S. ship.

The weather-patrol vessel’s enlisted ranks included white and black crewmen, while Samuels and newly promoted Lieutenant (junior grade) Jenkins also served on board her. Unlike in the U.S. Navy’s first desegregated ships, the Sea Cloud’s white and black crew members shared the same sleeping quarters and ate at the same mess tables. According to Skinner, the experiment “made me tense at times and I am sure made my Negro officers tense at times, but it worked.”

A forward-thinking commandant, Admiral Waesche had put his full support behind the groundbreaking effort despite the project’s initial rejection by Skinner’s immediate superiors. Waesche, who served as commandant from 1936 through the end of the war, deserves a great deal of credit for supporting the desegregation of the U.S. Coast Guard.

In early 1944, African-American Harvey C. Russell Jr. graduated from the Coast Guard Academy’s reserve officer training program. A natural leader, he would prove to be popular among Coast Guard officers and enlisted men no matter their racial background. Russell served briefly on board the Sea Cloud before joining Lieutenant Commander Skinner in the Coast Guard–manned Hoquiam (PF-5). This second desegregated Coast Guard vessel was a frigate that patrolled the northern Pacific, and as with the Sea Cloud, the integration effort was successful.

Skinner would serve as an adviser to the Navy in its first effort to desegregate a warship, the destroyer escort Mason (DE-529). Later, in 1949, President Harry S. Truman appointed Skinner governor of the Territory of Guam.

After his tour in the Sea Cloud, Lieutenant (junior grade) Samuels took command of a lightship converted into a net tender in the Panama Canal Zone, thus becoming the first minority officer to command a U.S. vessel in a combat zone. In 1945 Harvey Russell transferred to the Coast Guard–manned U.S. Army tanker TY-45 in the Southwest Pacific and commanded her all-white crew through 1946. Counting Healy and Samuels, Russell was the Coast Guard’s third African-American ship captain and the fourth minority skipper in the service.

Early in 1943, the Coast Guard began recruiting women for the SPARs (Semper Paratus/Always Ready), a female corps similar to the Navy’s WAVES and the Army’s WACs. For the war effort, the Coast Guard estimated it would need 8,000 enlisted women and 400 female officers; however, 12,000 women volunteered overall. Five African-American women enlisted and became members of the 10,000-strong SPAR corps that served during the war. The first to enlist was Olivia J. Hooker, who advanced to yeoman second class before the war ended. Hooker and the four other African-American SPARs were among the first minority women to don Coast Guard uniforms.

Valor Under Fire

During the war, thousands of black Coast Guardsmen went in harm’s way, and in the process, many sustained wounds. Others, such as African-American Warren Deyampert, an officer’s steward in the cutter Escanaba (WPG-77), made the ultimate sacrifice. In February 1943, Deyampert served as a tethered swimmer during efforts to rescue the crew of the U.S. Army Transport Dorchester. Deyampert repeatedly entered Greenland’s icy waters to save men from the torpedoed ship. He survived the dangerous mission only to die six months later in an unexplained explosion that sank the Escanaba with all but two crew members lost.

Minority service members gave their lives on other damaged or lost Coast Guard ships. These included the Muskeget (WAG-48), a cutter serving as a weather ship that was torpedoed in the North Atlantic with all hands lost, and the Serpens (AK-97), a Coast Guard–manned Liberty ship loaded with ammunition that mysteriously exploded off Guadalcanal in January 1945. The Serpens disaster resulted in the largest single loss of Coast Guardsmen during the war, with nearly 200 service members killed.

The heroism and sacrifice of black Coast Guardsmen during World War II did not go unnoticed. For example, African-American Louis C. Etheridge Jr., who commanded an African-American gun crew on board the cutter Campbell (WPG-32), earned the Bronze Star for his heroism in helping sink U-606 on 22 February 1943. He was the first minority Coast Guardsman to receive the medal.

That same month, Charles W. David Jr., a mess attendant in the cutter Comanche (WPG-76), volunteered to rescue survivors of the Dorchester from the freezing Greenland waters. David, who saved numerous victims of the lost ship, died a few days later of pneumonia. He was posthumously awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal and the Purple Heart, and in 2013 the Coast Guard named a cutter in his honor, the Sentinel-class WPC-1107. In April 1944, Steward’s Mate Emlen Tunnell saved the life of a burning shipmate in the aftermath of an enemy attack on the Coast Guard–manned Etamin (AK-93). A year later, Tunnell plunged into the waters off Newfoundland to save another shipmate, later earning him the service’s Silver Lifesaving Medal.

Training Ground for Greatness

For many blacks, wartime Coast Guard service was a prelude to greater things. These included Jacob A. Lawrence, a crewman on board the Sea Cloud who became a world-famous modernist painter. SPAR Olivia Hooker went on to become a distinguished professor of psychology at Fordham University, retiring at the age of 87. Alexander P. “Alex” Haley enlisted in 1939 as a steward’s mate and rose to become the first chief journalist in the Coast Guard. After 20 years, he retired to pursue writing and won awards as the author of such books as The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Roots: The Saga of an American Family. Later, he received the first honorary degree awarded by the Coast Guard Academy and became the namesake of a Coast Guard ship, WMEC-39, a medium-endurance cutter.

After Harvey Russell left the service, he joined Pepsi-Cola and, in the early 1960s, broke the corporate color barrier when he was promoted to vice president. In 1943 Russell’s friend and Sea Cloud shipmate Joseph Jenkins had received an invitation from the African nation of Liberia to serve as the civil engineer in charge of design and construction of that country’s infrastructure projects. However, Jenkins remained in the Coast Guard and after the war returned to Detroit, where he engineered the city’s rapidly expanding freeway system. Coast Guardsman Emlen Tunnell became a professional football star with the New York Giants and Green Bay Packers, and the defensive back was the first African-American inducted into the Professional Football Hall of Fame. In 1999 The Sporting News ranked him among the 100 greatest players in football history.

On 26 July 1948, President Truman signed Executive Order 9981 requiring the integration of the armed forces. But African-American Coast Guardsmen and women had already pioneered the way ahead for minorities in the U.S. armed forces and American society. African-Americans reached nearly 2 percent of the Coast Guard’s wartime population, a small figure compared to the 10 percent of blacks in the overall U.S. population at the time. However, it was a far larger percentage than African-Americans held in the service before the war. And, by the end of World War II, the Coast Guard had opened all its enlisted ratings, afloat and ashore, to black recruits; about one out of every five African-American Coast Guardsmen reached petty officer or warrant officer level.

During the 1950s and 1960s, black men and women serving in the Coast Guard enjoyed gradual increases in their percentage of the overall service population. They broke color barriers at the Coast Guard Academy, in the aviation branch, and in senior officer and enlisted ranks. During the following decades, African-Americans overcame one color barrier after another, building on a foundation of change brought about by World War II.