“The destruction goes beyond all description,” Ferdinand H. Gerdes of the U.S. Coast Survey wrote of the damage wrought by Union 13-inch sea mortars at Fort Jackson on the lower Mississippi in April 1862. “The ground is torn up by the shells as if a thousand antediluvian hogs had rooted it up. The holes are from 3 to 8 feet deep and are very close together, sometimes within a couple of feet. All that was wood in the fort is completely consumed by fire; the brickwork is knocked down, the arches stove, guns are dismounted, gun carriages broken and the whole presents a dreadful scene of destruction.”

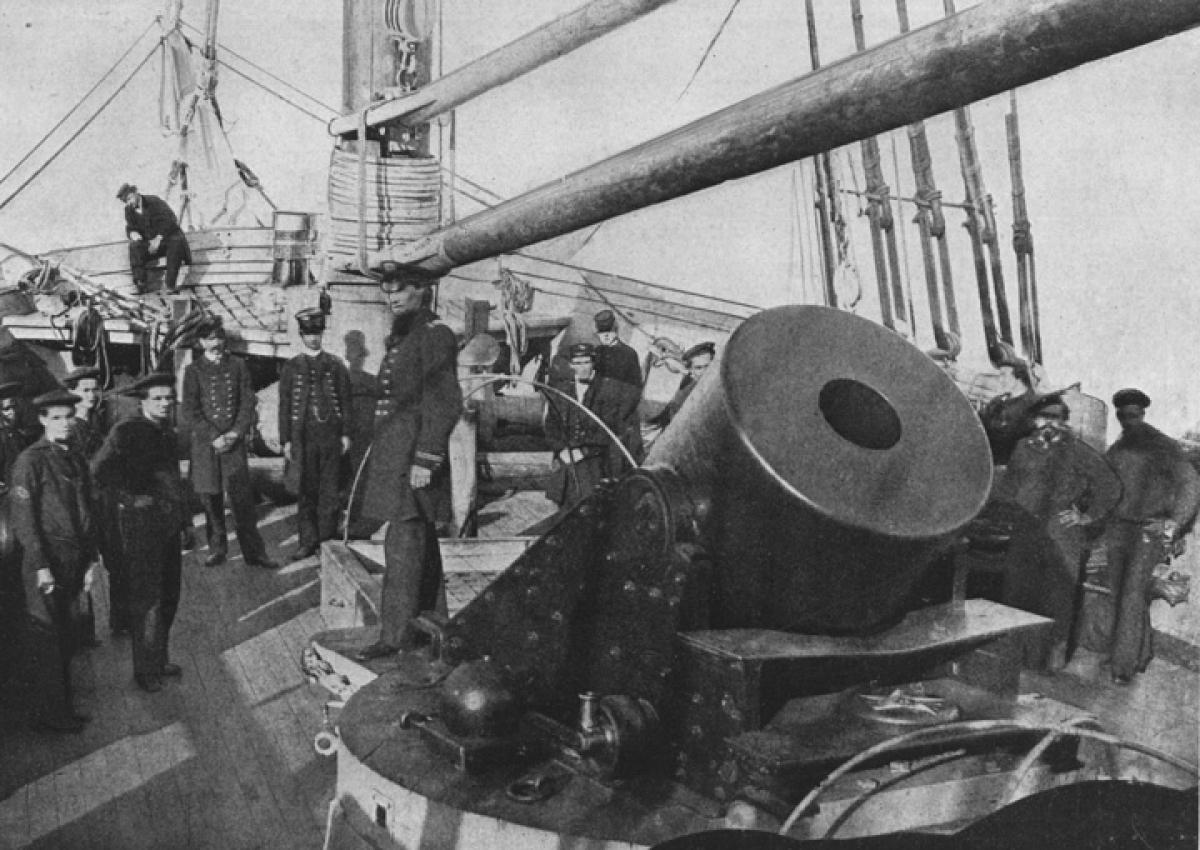

The 13-inch Civil War sea mortar was a formidable weapon. But the use of this type of gun was not new; since the 17th century, high-trajectory mortar fire from special vessels known as bombs or bomb ketches had been used for shore bombardment. Heavy ordnance was more easily moved about on ships than on land, and the large sea mortars were mounted on strong beds turned on vertical pivots. Their explosive shells, fired at high angle, easily cleared the walls of forts to strike the targets within.

The 13-inch weapon weighed 17,250 pounds and rested on a 4,500-pound bed, or carriage. With a 20-pound charge of powder and the mortar at a 41-degree elevation, it could hurl a 204-pound shell loaded with 7 pounds of powder more than 2¼ miles. At that distance the shell was in flight for 30 seconds. The range could be adjusted by altering the powder charge or changing the mortar’s elevation.

Union Major General John C. Frémont, commander of the Western Department, ordered the first Civil War mortar boats on 24 August 1861. Thirty-eight in number, they specifically were designed to engage Confederate river batteries. Designated by numbers rather than names, the 60-by-25-foot boats were in fact little more than rafts and of such low freeboard that the first two feet of their six-foot sloping sides were caulked to keep out water when the mortars were fired. The sides were slanted inward at the top and plated with half-inch-thick iron to protect against small-arms fire. The boats, which leaked badly, were moved about by tugs and proved so unwieldy that false bows and sterns had to be added to make them more maneuverable.

A 13-man crew, including a first and second captain, manned the mortar. To train the weapon, the platform, or “circle,” on which it was mounted was turned. Crewmen using curved “eccentric bars” inserted into cams along the circle’s edge first lifted the platform onto its rollers and pinned the bars in place. Others then used train tackles to turn the circle. When the mortar was properly positioned, the bars would be unpinned and the circle lowered. Because of the intense noise and reverberations inside the boat when the mortar was fired, after charging the weapon the crew would retire through iron side hatches to the open stern deck. The first captain would then fire the mortar by quickly pulling on a long lanyard whose opposite end was attached to a friction primer inserted in the weapon’s vent.

The first mortar boats were not ready in time for the Union victories in the battles of Forts Henry and Donelson in February 1862, but they joined Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote’s squadron on the upper Mississippi in March and participated in the Battle of Island No. 10 later that month. They also took part in other actions, including the shelling of Vicksburg during the 18 May to 4 July 1863 Union siege of that Confederate bastion.

Meanwhile, schooners mounting 13-mortars supported the drive by West Gulf Blockading Squadron commander Flag Officer David G. Farragut up the Mississippi. In November 1861 Commander David D. Porter had convinced Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that bombardment of Confederate Forts St. Philip and Jackson on the Mississippi below New Orleans by a flotilla of mortar vessels would be necessary in order to pass the strongpoints and capture the Crescent City. Porter pledged that both forts would be rendered ineffective, if not destroyed, within 48 hours.

President Abraham Lincoln gave his endorsement for the operation, and Porter supervised the purchase and fitting out of 20 schooners, ranging in length from 88 to 122 feet, and then took command of the flotilla. Each of the vessels mounted a 13-inch mortar as well as other guns, most carrying at least two 32-pounders. After bombarding Fort Jackson, the schooners, towed by steamers, followed Farragut’s oceangoing warships upriver and shelled Vicksburg from 26 June to 22 July 1862.

Despite Ferdinand Gerdes’ vivid description of Fort Jackson’s damage, however, 13-inch sea mortars did not live up to their hype. Foote had hoped they could reduce the Confederate positions along the Mississippi so that his gunboats could run past Island No. 10 to New Madrid, Missouri. He arrived above the island in mid-March with 7 gunboats and 10 mortar boats. No. 12 launched the first shell against Island No. 10 at 1440 on 16 March. Fired at their extreme range, the mortar shells could reach the batteries on the island, the Confederates’ floating battery, and the five Rebel batteries on the Tennessee side of the river. But because the mortars were firing diagonally across Phillips Point, the gun crews could not see their targets, and the only immediate effect of the shelling was to drive some of the defenders from their positions. That day the mortars fired nearly 300 shells.

The next day the bombardment’s lack of effectiveness was revealed when the Confederate shore batteries easily turned back an attack by Foote’s gunboats. Subsequent shelling had little effect. Sixty miles downriver, a seven-week mortar bombardment of Fort Pillow yielded the same poor results.

Foote, however, was never as forthcoming about the mortars’ performance as commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron Flag Officer Samuel Du Pont. In a 12 April 1862 letter to his wife, Du Pont assessed how 13-inch mortars on Tybee Island, Georgia, performed against nearby Confederate-held Fort Pulaski:

One item has disappointed me—those great mortars are a dead failure; they did nothing at all, went wild, burst in the air, and caused no apprehension at all to the garrison. I am worried about this because this is the great dependence, those 13-inch mortars, that our friends in the Gulf are looking to, to reduce the forts in the Mississippi.

Du Pont had reason to worry, for the mortars’ performance during Farragut’s New Orleans campaign was disappointing. Beginning early on 18 April 1862, Porter’s mortar schooners—all named instead of simply numbered—were towed into position by seven steamers. They moored some 3,000 yards from Fort Jackson along the riverbank, where they were protected by woods and a bend in the Mississippi. At 1100 those in position opened a bombardment, followed by the others at they came up.

Each mortar fired one shell about every ten minutes. At night, in order to provide some rest to the crews, each fired at a rate of one shell every half hour. For six days and nights they continued, expending a total of 16,800 shells, almost all of them at the fort and without notable result. The problem seems to have been the fusing; the shells either burst in air or buried themselves in the soft earth before exploding without major effect.

The Confederates responded by sending fire rafts down the river at night, but Union boat crews grappled these and towed them off without damage. Although the Union shells did dismount some of the guns in Fort Jackson, most of the Confederate crews bravely kept to their positions, and the defenders were able to remount most of the guns. Indeed, Rebel counterbattery fire on 19 April sank the mortar schooner Maria J. Carlton, killing and wounding some Union sailors. Porter, who was never one to admit failure, claimed that the first day’s mortar fire “was the most effective of any during the bombardment, and had the fleet been ready to move at once, the passage could have been effected without serious difficulty.” Despite the mortars’ lack of success, Farragut ordered his squadron to steam upriver past the forts, which it accomplished on 24 April.

Although 13-inch sea mortars failed to turn any Civil War battles, there can be no doubt that the sight and sound of their glowing shells arcing high across a dark sky and then exploding was awesome and had a strong psychological effect on Confederate garrison troops as well as Union attackers.