When one thinks of famous American warships and their captains in the War of 1812, one recalls the frigate Constitution and Isaac Hull, the frigate United States and Stephen Decatur, the brig Niagara and Oliver Hazard Perry, or the brig Saratoga and Thomas Macdonough. But no vessel and no captain did more damage gun-for-gun and ton-for-ton to the Royal Navy and British merchant shipping than the U.S. sloop-of-war Wasp and Johnston Blakeley.

Yet they are among the most forgotten figures in our second war with Great Britain. Blakeley, his crew, and the Wasp, lost at sea and largely lost to memory, lie in Lord Byron’s “deep and dark blue Ocean . . . without a grave, unknell’d, unconffin’d, and unknown.”

The Challenges of Secretary Jones

When William Jones left a Philadelphia commercial maritime career to assume the cabinet post of secretary of the Navy in January 1813, he confronted a series of political, strategic, operational, and personnel problems that continued throughout his nearly two-year career at the Navy Department. Politically, he found that Congress, in the jubilation over the victories of the Constitution and United States in the opening months of the war, had authorized the construction of ships-of-the-line and frigates that were expensive to build, would probably not be finished before the war was over, were blockaded easily, and required large crews. Strategically, he faced a two-front war on the freshwater seas along the Canadian-American border and on the world’s oceans, especially the Atlantic and Caribbean. Operationally, this Revolutionary War privateer captain wanted to concentrate more on the British merchant marine, where he felt the United States could have its greatest impact on Whitehall decision makers, rather than on attempting to score more victories over Royal Navy warships. Personnel issues revolved around insufficient manpower for his growing number of vessels plus a group of hot-headed young captains who sought glory and reputation trying to replicate the triumphs of Captains Hull and Decatur against Royal Navy men-of-war.

Were this not enough, the British Atlantic Coast blockade tightened and reached a climax on what we might call the “inglorious first of June” 1813, when HMS Shannon defeated the U.S. frigate Chesapeake off the Massachusetts coast, and Royal Navy blockaders chased Decatur’s squadron into New London, Connecticut, and trapped it there.1 On that one day the U.S. Navy lost nearly half of its oceanic operational strength. Meanwhile the U.S. frigate Constellation lay blockaded in Norfolk, from which she would never sail forth during the war.

The blockade forced Secretary Jones to modify strategic policy. He determined that naval operations should revolve around two major programs: first, the construction of warships on Lakes Ontario, Erie, and Champlain, which placed a severe demand on manpower needs from the seacoast to the interior; and second, concentration on commerce-raiding operations employing sloops-of-war rather than frigates or ships-of-the-line. Such small vessels were faster and much cheaper to build, required smaller crews, and could escape the blockade more easily than the larger ones. Recalling his Revolutionary War experiences, Jones foresaw the sloops-of-war operating much like, and in combination with, the privateers sailing from American ports.2

Jones’ objective was to divert Royal Navy resources away from the blockade toward a defense of the critical West Indian, Asian, and home-island trade routes. In addition, he expected the losses (and threats of more losses) would compel British mercantile interests to petition political leaders to rescind the Orders in Council and impressment issues that had brought the Anglo-American conflict into being. The commerce-raiding strategy ran against the desires of most of his captains, whose quest for ship-to-ship combat meant risking Jones’ precious vessels for little strategic gain and potentially significant losses of ships and crews.

The Wasp and Her Captain

Johnston Blakeley was born in Ireland in 1781; his family migrated to the United States two years later, and he grew up in Wilmington, North Carolina. He attended the fledgling University of North Carolina before entering the Navy as a midshipman in 1800. Blakeley had received more formal education than virtually all of his naval contemporaries. As a junior midshipman, he served with several of the new Navy’s most capable captains in the Mediterranean Squadron during the early phases of the Tripoli campaign. But he sailed home before Commodore Edward Preble took command of the squadron; thus Blakeley did not participate in the famous naval exploits of “Preble’s boys” that followed.

An indication of Midshipman Blakeley’s growing reputation came when Captain John Rodgers named him acting third lieutenant of the frigate Congress. Blakeley and his shipmates Robert Henley and William Allen became Rodgers’ favorite midshipmen, and they would be destined for fame as commanders of the Eagle, Argus, and Wasp during the War of 1812. Blakeley, like several of his contemporaries, took a furlough from the Navy; he undertook a 14-month cruise on the Bashaw, sailing from Baltimore to Buenos Aires and back. As did most of the members of this “mercantile minority” in the officer corps, Blakeley broadened both his navigational skills and his management of sailors and their discipline.

Upon his return, Blakeley discovered that he, along with 60 others, finally had been promoted to lieutenant. He stood 25th on this list and returned to active service. Soon there arrived orders to serve as first lieutenant of the brig Argus, which would be engaged in the unpleasant duty of enforcing the Embargo Act against New England’s defiant mariners. His enhanced reputation with the Navy Department brought an assignment in 1809 as first lieutenant on board the corvette John Adams. She left that December on a diplomatic mission to France and returned the following April.

In 1811 he received orders to take command of the schooner Enterprize, then lying at Hampton Roads, and take her to the St. Marys River between Georgia and the Spanish colony of Florida. During his command she was rerigged as a gun-brig. Although Congress had declared war on Great Britain in June 1812, it was nearly a year before Blakeley and his combat-anxious officers secured reassignment to Portsmouth, New Hampshire; sailing from there they soon captured the British privateer schooner Fly. For the first time in his life, Blakeley received prize money. Upon his return to Portsmouth Blakeley learned two pieces of good news—he received promotion to the rank of master commandant and orders to command a sloop-of-war being built in Newburyport, Massachusetts.

In early 1813 Secretary Jones had secured congressional approval to build six sloops. One of these was the fifth vessel in U.S. naval history to be named the Wasp. She was a 509-ton, 117-foot, flush-decked, ship-rigged vessel that carried two 12-pounder long guns and twenty 32-pounder carronades. Her full crew numbered 173. Designed by William Doughty, these “corvettes,” as the French called them, had to be fast enough to outrun larger men-of-war, strong enough to engage opponents of similar size, durable enough to sustain a damaging victory, and large enough to convey water and provisions for an extended voyage.

Closely following Doughty’s design, this corvette would be built in Newburyport for over $25,000. Her shipwrights employed the best white oak, rot-resistant locust and cedar, and white pine in her construction. Unfortunately, there was none of the exceptionally hard Southern live oak that served the Constitution so well, but wartime exigencies required a New England substitute. When launched on 18 September 1813, her first and only commander, Master Commandant Blakeley exclaimed: “From the rocks and sands and enemy’s hands, God save the Wasp!”3

Young Officer, New Ship

Secretary Jones understood giving command of one of the few instruments of his commerce-raiding strategy to a very inexperienced young officer was the consequence of “the rapid increase of our naval force, the promotion of young officers has been necessarily very rapid; and whose experience and talents that have exalted our flag are comparatively few in number.”4 In delivering command of this sleek, fast, nimble, and heavily armed vessel to Blakeley, the secretary assumed the risks to his strategic concept that the newly promoted master commandant represented. Would he, like so many of his contemporaries, be more concerned with fighting enemy warships than destroying British commerce?

Slowly and surely the ship received her rigging, canvas, oaken casts, water, provisions, anchors, cannon, and powder and shot. Blakeley assembled his officers, the most critical being Sailing Master James E. Carr, who was responsible for navigating, sail handling, and logbook recording. A veteran of the Constitution’s early battles, newly promoted James Reilly reported aboard as first lieutenant. An old Blakeley friend, Thomas Tillinghast, served as second lieutenant, and Midshipman Frederick Baury, an acting lieutenant, held the third lieutenancy. Midshipman David Geisinger, the same age as First Lieutenant Reilly, was an experienced and valuable addition to the ship’s officer corps.

Benefiting from the increased income of a master commandant, on the third day of Christmas 1813, at Boston’s Trinity Church, Blakeley wed Jane Anne Hoope, the daughter of a late merchant of St. Croix. The couple took up residence at Locke’s Hotel in Newburyport while the impatient captain of the Wasp awaited the arrival of the vessel’s carronades. In the end, only 18 of the promised 20 reached him. He enviously received notice that the Wasp’s sister ship, the Frolic captained by Joseph Bainbridge, left Boston on 18 February on a cruise. (Instead of taking merchantmen, she would be captured by a Royal Navy man-of-war off Cuba. Another corvette, the Peacock, commanded by Lewis Warrington, sailed out of New York in mid-March on a cruise that would net no merchant ships but did result in a victory over the brig HMS Epervier off Cape Canaveral.) Frustrated and anxious to set sail, Blakeley remained with his bride in Newburyport.

Finally commissioned, the Wasp sailed 20 miles north to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on 28 February. There Blakeley acquired a green crew and awaited orders. Although the orders arrived in March, it would be another six weeks before the Wasp left Portsmouth. Secretary Jones’ orders contained several critical components. First, he discouraged the custom of taking prizes into friendly ports unless close by the point of capture, as they depleted the size of the corvette’s crew and were subject to recapture by the Royal Navy. Prizes were to be destroyed. Obviously, water, provisions, and munitions captured could be used to resupply the Wasp’s needs. Second, captured British crew members were to be retained on board the Wasp and returned to the United States to be exchanged for captured Americans. This directive placed a burden on the capturing vessel, as prisoners consumed provisions and presented a security risk to the Wasp. Blakeley questioned the advisability of this requirement since it could force his return to the United States prematurely. Subsequently he paroled prisoners in defiance of this instruction.

The secretary directed the Wasp to cruise off the Azores and then to proceed to the entrance to the English Channel, followed by a short visit to Cape Finisterre and along the Portuguese coast; after refitting at Lorient, France, she was to journey to the Shetland Islands. As the autumnal weather worsened, she was to sail off Madeira for a few weeks before making a circuit of the Caribbean from present-day French Guiana to Honduras and Florida, and then return to Georgia, where Blakeley was to touch down “for information and refreshments.” The mission was to inflict maximum damage on the British merchant marine while making it difficult for the pursuing Royal Navy to determine just where the Wasp would be at any given time.

Finally, as a consequence of James Lawrence’s loss of the Chesapeake in 1813, Secretary Jones forbade all his commanders from “giving or accepting of a challenge, to fight ship to ship; which injunction you will strictly observe.”5

Cruising the Atlantic

Blakeley’s enlisted crew slowly assembled; it contained 47 “able seamen” with at least some oceanic experience and 68 “ordinary seamen,” a catchall phrase that included both occasional coastal sailors and green farm boys. Although his officers and noncoms came from all along the Atlantic coast, most of the junior enlisted men were from Federalist New England. Finally, the young captain bade farewell to the now-pregnant Jane Anne Blakeley and, like so many sailors then and now, left her to cope with the worries of a campaign widow and the increasing complications of bearing their child. On the afternoon of 2 May 1814, the Wasp left Portsmouth and sailed into the Atlantic. With her canvas wings unfurled in a fine northwest breeze, she stood out toward the darkening east with no enemy blockaders in sight. Captain Blakeley entertained “the most favorable presages of her future performances.”6

For the first several days most of his crew suffered from seasickness, but Blakeley conducted live-fire exercises, reset the rigging, holystoned the decks, and maintained his vessel. En route to his first station he encountered the French brig Olivia, carrying dispatches indicating Emperor Napoleon’s abdication. That information cautioned him that French ports might not be friendly to American vessels.

On 3 June Blakeley began the work Secretary Jones had prescribed. Southwest of the captain’s native Ireland, the Wasp took her first prize, the 207-ton barque Neptune. After the men took aboard prisoners, sails, blocks, cordage, and provisions, Lieutenant Baury set the Neptune afire. Eight days later the brig William met the same fate. Now in the sea lanes off the Irish coast, the Wasp soon captured two more merchantmen, the brig Pallas and the galliot Henrietta. Now with 38 prisoners on board, Blakeley disobeyed Secretary Jones’ orders and put the captain of the destroyed Pallas in command of the Henrietta to sail to England with the prisoners as parolees, pledged not to serve against the United States unless exchanged. Blakeley knew full well that the British would not recognize these paroles, but he no longer had to feed these men, and he wanted to remain at sea longer with an undiminished crew.

The afternoon of 27 June found the Wasp taking her biggest prize yet—the 325-ton Orange Boven, out of Bermuda carrying a rich cargo of sugar and coffee. As a letter-of-marque ship, the Bermudian capitulated only after Blakeley unleashed a broadside into her. Despite the temptation to take such a richly laden prize to a neutral port, Blakeley finally had her scuttled. At this point, the Wasp had taken more prizes than all the other U.S. Navy sloops combined.

The London press was outraged at this affront to British shipping so close to the home islands and claimed the Wasp’s crew consisted of Scottish and Irish desperadoes who were “most bitter in their invective against their native soil.”7 Actually, the only Irishman may have been the ship’s captain, who had left the Emerald Island age the age of two.

This tirade must be seen in light of the concurrent impact of American privateers operating in British home waters. For instance, Captain Thomas Boyle of the Chasseur sailed the Bristol Channel and defiantly declared a blockade of the British Islands to counter the blockade the Royal Navy had imposed on the United States. Captain Samuel C. Reid took £250,000 in prizes before his General Armstrong was cornered by five British men-of-war off the Azores. The Royal Navy’s pursuit of the General Armstrong and its aftermath caused a delay in sending British Army reinforcements to the New Orleans campaign, which might have affected the outcome of that invasion. (See “A Daring Defense in the Azores,” April, pp. 28–32.) The most spectacular American privateer, the swift Prince de Neufchatel captained by John Ordronaux, took 26 prizes in the English Channel about the same time the Wasp was conducting her cruise. (See “Obstinate and Audacious,” April, pp. 22–27.) Blakeley’s conduct played directly into Secretary Jones’ concept that the sloops-of-war and privateers jointly could impact British public opinion regarding the continuation of the conflict.

A Wasp Stings a Reindeer

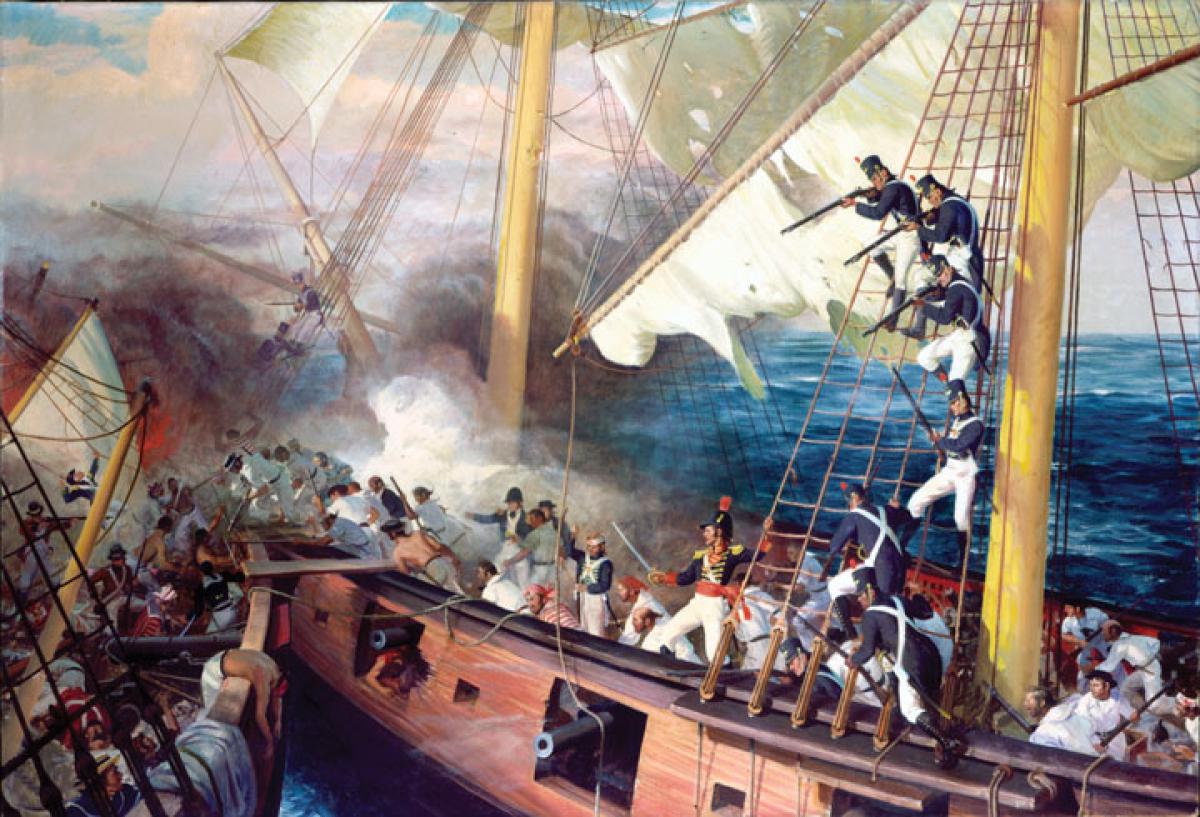

Like his Navy contemporaries, Blakeley knew that his reputation would be enhanced with a victory over a British man-of-war. Opportunity presented itself early in the morning of 28 June, when a sail sighted on the weather beam proved to be the sloop HMS Reindeer, William Manners, commanding. The Wasp could have outsailed the British vessel, but the opportunity was too tempting, despite the secretary’s prohibitive orders about picking fights with British warships. Neither Blakeley nor Manners had been in ship-to-ship combat before, and both captains wanted to prove their combat skills. Manners held the weather gage, but Blakeley had greater weight of metal and a larger crew.

Eleven hours after the initial sighting the battle began, with Reindeer firing the first rounds. At 1524 the Wasp closed to within a ship’s-length range and unleashed a starboard broadside that severely wounded Manners. Ten minutes later Blakeley directed his quartermaster to put the helm hard alee. The maneuver went awry, and the Reindeer crossed the Wasp’s bow and poured shot directly into her prow at point-blank range. Fortunately these triple-shotted rounds did not penetrate the Wasp’s oaken bow. The American then crossed her opponent’s stern and commenced a port broadside. The British attempted to board, but accurate sailor and Marine gunnery soon killed Manners and his first lieutenant while the British sailing master, purser, and quartermaster collapsed wounded to the deck. Fighting hand-to-hand, the outnumbered Britons finally succumbed, and the captain’s clerk, now the vessel’s most senior officer, surrendered the Reindeer.

The butcher’s bill shocked both sides. The Wasp had 11 men killed and 18 seriously wounded. The slaughter on the Reindeer boggled the imagination—33 died and another 34 lay seriously wounded. More than half her courageous crew were casualties.

For the Americans, the Wasp’s victory validated their seamanship and bravery. The repulse of the British boarders and the death of the Reindeer’s captain, a member of one of Britain’s most distinguished aristocratic families, avenged the loss of James Lawrence on board the Chesapeake a year earlier. Despite allowing his opponent to rake his vessel, Blakeley and his inexperienced crew, operating far from home, had bested an opponent with more combat-experienced officers and men operating close to their home waters. When news of the victory reached America, the nation lauded Master Commandant Johnston Blakeley as a hero.

After committing the remains of the dead of both ships to the sea, Blakeley had the Reindeer burned and he sailed his damaged vessel off with more than 100 prisoners, many of them seriously wounded. Again, with the cooperation of a Portuguese merchantman he met, Blakeley paroled several of the officers and men of the Reindeer and Orange Boven, and again the Admiralty declared the paroles “null and void.”

Lorient Interlude and English Channel

Meanwhile, the Americans sailed unmolested into neutral Lorient, France, on 8 July after capturing two more English merchantmen en route—the brig Regulator and schooner Jenny. Both were sent to the bottom with their cargoes of wine and “sweet-oil.” With seven merchant vessels and one sloop-of-war to her credit, the Wasp and her captain had carried out what Jones wanted, hitting the British in their pocketbooks.

To Blakeley’s surprise, the French cooperated with him and showered his crew with cheers as they refitted in the Brittany port. The defiance and audacity of the young republic’s navy against the “Mistress of the Seas” secured admiration and goodwill among Frenchmen who had been blockaded by the Royal Navy for a generation. France’s new royal government ignored British protests and allowed Blakely to slowly repair his sloop. At the same time the Wasp received 14 new able seamen and a ship’s steward to replace those killed or incapacitated. She departed Lorient on 27 August with 167 officers and men, 6 fewer than when she had left Portsmouth three months earlier.

With a fair wind and a favorable sea the Wasp began a cruise near the approaches to the English Channel and chased every sail she sighted. There was no better indication of increased commercial shipping following the demise of Napoleon than that the first ships Blakeley’s crew boarded were neutral Portuguese, Dutch, French, and Swedish. But at the end of August the Americans’ luck changed—the merchant brigs Lattice and Bonacord were taken and scuttled.

The Glorious First of September

Then on 1 September, through the fog and haze, the Wasp’s lookouts spotted the golden prize sought by all American warships and privateers—a scattered British convoy. It was guarded by the 74-gun Armada, which was towing the disabled ketch Connoly. Most of the convoy was ahead of the encumbered Armada and clustered near the bombship Strombolo. The Wasp discovered the abandoned Mary, laden with military stores from Gibraltar, attacked her, and set the prize afire before the Armada realized what was happening. Blakeley’s vessel disappeared into the haze before the double-decker could engage her.

That afternoon the Wasp entered waters patrolled by the sloop HMS Tartarus, commanded by Captain John Pasco, and two 18-gun brigs, the Avon, Sir James Arbuthnot, and Castillian, Lieutenant George Lloyd, commanding, which were seeking the infamous Baltimore privateer Chasseur, thought to be in the area. They had no idea the Wasp was at sea. The Tartarus chased one American privateer while the Castillian went after another. Then the Castillian’s crew heard staccato gunfire to the east. She immediately headed toward the flashes of light in the darkening sky. There, some eight miles away, the Wasp was fighting the Avon in a bloody exchange of 32-pounder carronades. By 2200 hours the seriously wounded Captain Arbuthnot learned his first lieutenant was dead, more than a third of his crew were casualties, his mainmast had crashed over the side, and the ship’s hold contained seven feet of rising water.

The British captain surrendered just before the Wasp’s lookouts spotted the approaching Castillian. Unwilling to engage a fresh man-of-war, Blakeley sailed away, pursued by the Castillian for more than an hour; a British broadside sailed over the American vessel, damaging sails and rigging but no sailors. All the while the Avon kept firing distress signals, and finally the Castillian returned to her sinking sister ship just in time to rescue her survivors before she plunged beneath the waves. The Tartarus joined the Castillian the next day, but by then the Wasp had disappeared.

The Wasp’s destruction of a ship filled with military stores, a comparatively armed man-of-war, constituted one of the greatest achievements of the U.S. Navy in its young history. In one day Johnston Blakeley and his crew achieved a reputation for naval professionalism and fame that endures, at least among the small cult of War of 1812 naval aficionados. No amount of British court-martial apologetics can excuse the ineffective Avon gunnery that, despite a ten-to-eight disadvantage, failed to inflict enough damage on its American opponent that she could not escape from the Castillian. And the Wasp accomplished all this not far from British home waters.

The Vanished Victor

For the next several days the Wasp’s crew knotted and spliced the rigging, bent new courses and topsails, removed four 32-pound round shot from the hull (noting that the British shot outweighed the American by a pound and a half), and returned to capturing British merchantmen. Blakeley modified Secretary Jones’ orders by not cruising to the Shetland Islands. Instead he headed south, capturing the heavy-laden brig Three Brothers and later the brig Bacchus. After an exchange of usable cargo to the Wasp, both went to Davy Jones’ Locker. West of Madeira on 21 September, the Wasp captured her most valuable prize—the Baltimore-built, British-captured, copper-bottomed clipper ship Atalanta, bound for Spanish Pensacola. Because her valuable cargo was allegedly French and not British, the ship’s captain warned Blakeley that if he destroyed the cargo he would be liable for ruining neutral goods. While the Wasp’s captain was not fully convinced of this argument, he decided to send the Atalanta to the United States for adjudication.

Breaking from his practice with the previous 12 prizes, Blakeley ordered his protégé, Midshipman David Geisinger, to take the Atalanta to an American port. The captain’s orders were very specific: Geisinger was to avoid any sighted sail “by all the means in your power. The time of your arrival is of little interest compared with your getting in safely.”8 For 45 days, the Atalanta and her skimpy 11-man crew plied the Atlantic waters, narrowly escaping a suspected British privateer before sailing into Savannah Harbor on 4 November. Little did Midshipman Geisinger know that when he had waved goodbye to his captain and fellow Wasp shipmates, he would never see the any of them again.

The last confirmed sighting of the gallant sloop-of-war was by the Swedish brig Adonis on 9 October 1814, off the Cape Verde Islands. Blakeley took aboard two American midshipmen who were on parole to England and then sailed off, presumably for the Caribbean. For months thereafter, there were rumors of Wasp sightings but no confirmations. In all probability, she was caught up in a seasonal storm in Hurricane Alley, with her weakened rigging, heavy carronades, and low freeboard contributing to her demise.

Undoubtedly the loss of the Wasp has much to do with Blakeley’s modest public reputation. Five more vessels carried the name Wasp in American history, two of them World War II aircraft carriers, CV-7 and CV-18. The latest is an amphibious assault ship (LHD-1) commissioned in 1989. Three vessels have honored Johnston Blakeley, torpedo boat 27 (1900–19), destroyer DD-150 (1918–45), and the frigate USS Blakely (FF-1072), which was also named for his great-grandnephew, Vice Admiral Charles A. Blakely (1879–1950), who spelled the name without the final “e.”

Johnston Blakeley’s promotion to captain came on 24 November, two weeks after the birth of his daughter in Boston. His widow received $8,100 in prize money and a $50 monthly pension until she remarried. Congress voted Blakeley a gold medal and a sword; the state of North Carolina provided his daughter with a pension for her education until she reached the age of 16, plus a silver service. As was so common during the War of 1812, the gallantry of warriors stirred poetic verse. An anonymous poem titled “On the Wasp, Sloop of War” eulogized:

Too long on foaming billows cast,

The battles fury bray’d;

And still unsullied on thy mast

The starry banner wav’d;

Unconquer’d will Columbia be

While she can boast of sons like thee.9

No other American warship in the War of 1812 achieved so much. None of the other sloops whose commerce raiding Secretary Jones hoped would force the British to conclude peace did more toward that objective. With her victories over the Reindeer and Avon, no other American ship and no other American captain accomplished two ship-to-ship victories over Royal Navy opponents on a single cruise. As the anonymous poet hoped, for 200 years the Navy and the nation continue to boast of sons and daughters who follow unknowingly beneath the “starry banner” in the tradition of Johnston Blakeley and the crew of the fifth USS Wasp.

1. W. M. P. Dunne coined this parody on the “Glorious First of June” victory of the Royal Navy over a French fleet in 1794 in “‘The Inglorious First of June’: Commodore Stephen Decatur on Long Island Sound, 1813,” Long Island Historical Journal, vol. 2, no. 2 (Spring 1990), 201–20.

2. A summary of the issues relating to privateering in the Revolutionary era that influenced Jones’s attitudes is found in Michael J. Crawford, “The Privateering Debate in Revolutionary America,” Northern Mariner, vol. 21, no. 3 (July 2011), 219–34.

3. For a thorough biographical study, see Stephen W. H. Duffy, Captain Blakeley and the Wasp: The Cruise of 1814 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001); quote is from 110.

4. Quoted in Kevin D. McCranie, Utmost Gallantry: The U.S. and Royal Navies at Sea in the War of 1812 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2012), 224. For an overview of Jones’s policies and their impact, see McCranie, “Waging Protracted Naval War: The Strategic Leadership of Secretary of the U.S. Navy William Jones in the War of 1812,” Northern Mariner, vol. 21, no. 3 (April 2011), 143–57.

5. Jones to Blakeley, 14 March 1814, quoted in Duffy, Captain Blakeley, 157–61.

6. Blakeley to Jones, 2 May 1814, quoted in Duffy, Captain Blakeley, 167.

7. Duffy, Captain Blakeley, 202.

8. Blakeley to Geisinger, 23 September 1814, quoted in Duffy, Captain Blakeley, 261.

9. Duffy, Captain Blakeley, 289.