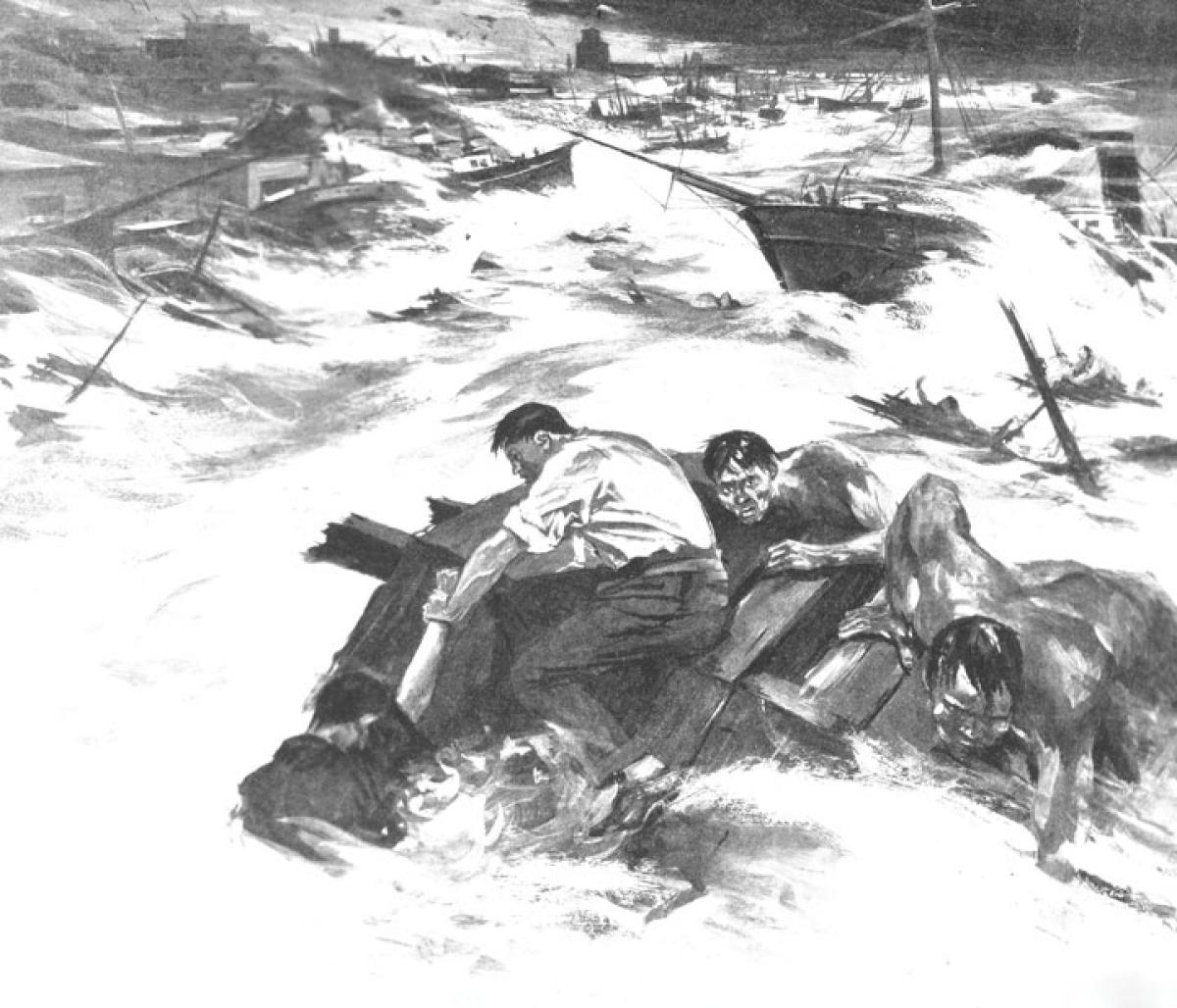

In September 1900, with little forewarning, a tremendously powerful hurricane struck the Gulf Coast. The storm made landfall a few miles west of Galveston, Texas, on Saturday, 8 September. The “Great Galveston Hurricane” proved far deadlier than any man-made, environmental, or weather-related event in U.S. history, with approximately 8,000 people killed in Galveston and roughly 2,000 more lost along other parts of the Gulf Coast. That death toll is greater than the combined casualty figures for the 7 December 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and Hurricane Ike, which devastated Galveston in 2008.

In 1900 the U.S. Coast Guard’s predecessor services were well represented in the Galveston area. The region boasted several U.S. Lighthouse Service aids to navigation, including three screw-pile lighthouses, whose design combined the keeper’s quarters and lantern room on top of iron legs augured into shallow water. The Lighthouse Service also had a 117-foot lighthouse, a brick tower sheathed in cast-iron plates, at Bolivar Point. Manned by Harry C. Claiborne, Bolivar Light was east of Galveston, on the opposite side of the channel connecting Galveston Bay to the gulf. And a lightship, 82-foot-long LV-28, had marked the entrance to the city’s harbor for 36 years; mounted high on a mast, her light could be seen for ten miles.

In addition to the Lighthouse Service, the U.S. Life-Saving Service maintained a station at the eastern tip of Galveston Island. Supervised by veteran keeper Captain Edward Haines, the station was located on Fort Point, which had served as a strategic military location for generations. In fact, just before the hurricane struck, the U.S. Army had nearly completed work on a new fortification, Fort San Jacinto, which stood not far from the lifesaving station.

Only 200 yards away from the station was the Fort Point Lighthouse, a screw-pile structure manned by Charles D. Anderson. A former Confederate Army colonel, Anderson had commanded Fort Gaines, at the entrance to Mobile Bay, until Union troops and naval forces under Rear Admiral David Farragut captured it in August 1864. By 1900 he was 73 years old; however, he must have enjoyed a certain sense of security with a fully manned lifesaving station on one side and a modern U.S. Army outpost on the other.

Before the storm’s arrival, Galveston’s waterfront bustled with activity. Several steamships were moored at the docks, including the Kendal Castle, a British steamer of the Castle Line newly arrived from Antwerp, Belgium, and tied up at Pier 31. Farther along the waterfront, the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service vessel Galveston was moored at a wharf near the port’s immense Elevator A, considered one of the world’s largest grain elevators. The steam-powered Galveston measured 190 feet in length and carried a crew of 32 officers and men. Permanently stationed at the port, the cutter enforced customs and quarantine laws, conducted search and rescue operations, and carried out other service missions.

The Hurricane Arrives

In late August 1900, a tropical depression formed in the Atlantic and developed into a tropical storm before passing over Cuba, drenching the island with two feet of rain. The National Weather Bureau had few of the technological tools available to present-day weather forecasters and was unaware of the storm’s track into the northwest Gulf of Mexico, where it quickly grew into what would now be classified as a Category 4 hurricane. The storm took Galveston by surprise because its initial winds blew from the north, not from the east, and were mixed with just light rain. Late in the morning on Saturday, 8 September, the northerly winds gradually increased in strength, pushing water in Galveston Bay south toward Galveston Island. But the north wind also pent up the hurricane’s tidal surge, building up in the gulf, on the opposite side of the barrier island.

Lighthouse, Life-Saving, and Revenue Cutter service personnel had little forewarning of the hurricane, but they began preparing for heavy weather anyway. At Fort Point, the lifesaving crew kept busy in the morning pushing floating debris away from the station and securing their boats. Nearby, Anderson kept tabs on the water level from his elevated lighthouse. To the east at Bolivar Point, Claiborne began stockpiling provisions in his tall lighthouse just in case the flooding continued. And on board the Galveston, Captain Charles T. Brian watched the barometer for signs that a hurricane was on its way. He also ordered mooring lines tightened, chains added to the hawser lines, and additional anchors set to secure his mooring.

The point of no return arrived early Saturday afternoon, as conditions rapidly deteriorated. Around noon the north winds grew in intensity to nearly 50 mph and dense cloud cover and heavy rain descended on Galveston; they would remain there the rest of the day. By about 1300, Haines and two surfmen tried to row a boat the short distance from their lifesaving station to the Fort Point Lighthouse to evacuate Anderson and his wife before the rising water swept away the structure. But the wind blew the oars out of the oarlocks and pinned their boat against the rock jetty extending between the station and the lighthouse. The men could do nothing more and barely managed to return to the station.

At around 1400, the storm closed in on the south Texas coast. Now exceeding 50 mph, the wind changed direction from north to northeast, releasing the gulf storm surge, which the northerly wind had been pushing offshore. By the time local residents realized the deadly circumstances facing them, floodwaters had risen dramatically and wind speeds reached gale force. At this point, about 50 residents sought safety on board the Galveston.

At Bolivar Point, the storm surge flooded the low-lying peninsula and waves broke against the base of the lighthouse tower. Approximately 125 locals found refuge in the structure, while the wind and water began swirling around it. That afternoon, the floodwaters halted a small passenger train approaching the Bolivar Point ferry terminal to meet the boat for Galveston. Of the train’s nearly 100 riders and crew, only nine braved waist-deep water to seek the safety of Bolivar Light’s tower. They were the last to gain entry before floodwaters sealed off the lighthouse’s first-floor entrance. The rising water surrounded the train, trapped the rest of the riders and crew within the passenger cars, and eventually drowned them all.

By 1500 the surge had flooded lower portions of Galveston to a depth of five feet. For many in the city’s inundated East Side there was nowhere to turn, and by 1530 reports of the death and destruction there began to reach the Galveston. Captain Brian considered sending a small boat to assist the stricken people, and Assistant Engineer Charles S. Root volunteered to lead the rescue party. After a call for volunteers went out to the ship’s company, eight crew members stepped forward to accompany Root.

At 1600 Root and his crew set out on a mission more common to Life-Saving Service surfmen than to cuttermen. The group quickly overhauled the Galveston’s whaleboat, dragged it over nearby railroad tracks, and launched it into the city’s flooded streets. The high winds rendered the oars useless, so the men warped the boat through town using a rope system. Seaman James Bierman would swim through the flooded streets with a line, tie it to a fixed object, and the crew would then haul in the line. Using this primitive, time-consuming process, the cuttermen rescued numerous victims from the city streets’ roiling waters.

Picking Up Momentum

By late afternoon, the hurricane began arriving in full force. Haines decided to abandon the lifesaving station at Fort Point and got his wife and crew into a lifeboat. The seas were heavy, and the surge swept immense quantities of wreckage against the station. Fearing that the boat could be damaged by the storm-tossed wreckage, Haines changed his mind and decided to remain in the station, hoping the structure would survive the high winds and heavy seas. When the water reached three feet from the top of the station’s first floor, the flooding seemed to near its peak. After getting out of the boat, crewmen had begun cutting holes in the second floor of the building to allow the water to pass freely between levels.

At around 1700, the wind’s direction suddenly shifted from the northeast to east, and the hurricane’s winds blasted through the doors and windows on the east side of the lifesaving station. Haines changed his mind again, deciding the lifeboat was probably the only means of survival. He ordered the crew to open the doors on the building’s north side in order to get the boat out, but a heavy sea broke into the boat room, lifted the craft from its carriage, and threw it against the station’s beach cart, punching a hole in the hull. Crew members had to use axes to cut open the doors against which the boat lay broadside. Meanwhile, it seemed certain that the building would collapse and crush everyone trying to escape.

A little more than an hour later, the Galveston Weather Bureau anemometer registered more than 100 mph before a wind gust tore it off the roof of the building; however, bureau officials estimated that between 1830 and 2000, the sustained wind speed increased to 120 mph. By this time, Assistant Engineer Root and his rescue party had returned to the Galveston with more than a dozen survivors. Heavy winds were taking an awful toll on the cutter, stripping away rigging and blowing the launch off the ship. Meanwhile, wind-driven debris shattered the windows and skylights in the pilothouse, deckhouse, and engine room.

By early Saturday evening, Haines realized the situation was hopeless and told his lifesaving crewmen they should find a way to save themselves. Meanwhile, he and his wife hoped to ride out the storm in the lifeboat. Some of the men believed that their chances of survival were better on the top floor of the station house, so three of them gained the stairway and climbed up, passing down ropes on the outside of the building for the others. Haines and his wife had remained in the boat, but the sea was now breaking over them and tossing the craft on its beam ends.

Haines’ wife begged him to get her to the top floor of the station, so the couple climbed to the building’s exterior gallery, a rope was tied around her, and Haines lifted his wife to the crew members above, who hoisted her over the roof. While lifting his wife, the gallery under Haines gave way, and he was swept into the lifeboat. As the storm blew the boat away from the station, the keeper shouted to the men on the roof to protect his wife. Shortly thereafter, he realized two of his men were clinging to the lifeboat and pulled them in to ride out the hurricane.

Peak of the Storm

Sometime that evening, the hurricane reached its climax in Galveston. At 1930 Weather Bureau officials recorded an instantaneous four-foot water-level rise. Experts estimate wind speeds that night likely reached 150 mph, with gusts up to 200 mph. The wind sent grown men sailing through the air and toppled horses to the ground. The barometric pressure dropped below 28.50 inches, one of the lowest marks on record at that date, and the storm surge reached its highest level—more than 15 feet above sea level. The water raised the Galveston so high that she floated over her own dock pilings. Their tops bent but fortunately did not puncture the cutter’s hull plates.

In Galveston Harbor the Kendal Castle broke loose from her moorings and soon began drifting around the bay. About seven miles north of Galveston, she collided with the Halfmoon Shoal Lighthouse, obliterating the screw-pile structure and killing its keeper, Charles K. Bowen, whose body was never found. As one witness recalled, “we passed within a few hundred yards of where the Halfmoon Lighthouse once stood, but could see no evidence of the lighthouse, it being completely washed away.” The Bowen family suffered much more tragedy, as the storm claimed the lives of the keeper’s father, wife, and daughter in Galveston.

Of the area’s three screw-pile lights, only the Redfish Bar Cut Lighthouse managed to escape the wrath of the hurricane, but just barely. Newly commissioned the previous March, the structure marked a channel through a shallow bar that bisected Galveston Bay. It must have seemed strange to the keeper when a darkened ship appeared in the distance being driven toward his lighthouse by Category 4 winds. Just as it seemed the ship would crush the beacon, the ghostly vessel veered slightly and passed silently only a few feet away.

Hurricanes had blown Galveston lightship LV-28 off station many times before, but none could compare with the 1900 storm. The 82-foot wooden vessel relied on sails for power and was at the complete mercy of the storm, which tore her from her moorings and parted her anchor chain. Ripping away her windlass and whaleboat, the winds collapsed one of the ship’s two masts. The hurricane drove the vessel several miles up Galveston Bay before her crew dropped the spare anchor, which held fast until the seas abated. Fortunately, LV-28 did not wash ashore and no crew members lost their lives.

By 2000, Charles Root was ready to make a second trip into the city’s streets. Darkness had fallen, and when he called for volunteers, the same men from the first rescue party stepped forward. The wind still made use of the oars impossible, so the crew waded and swam as water depth allowed, warping the boat from pillar to post. Meanwhile, buildings toppled over and hurricane winds filled the air with deadly projectiles, including slate roof tiles. Nevertheless the crew managed to rescue another 21 people. Root’s men housed these victims in a structurally sound two-story building and found food for them in a nearby abandoned store. Next, the cuttermen moored the boat in the lee of a building and took shelter from the flying debris.

At Fort Point, Colonel Anderson watched as the storm surge carried off equipment on his screw-pile lighthouse’s lower deck, including a lifeboat and storage tanks for fresh water and kerosene. The rising water had overrun Fort San Jacinto and all other man-made structures in the area, and it appeared as if Fort Point Lighthouse was drifting on a stormy sea. True to his mission, the keeper kept the light burning throughout much of the storm, even though any ships on the open water were either drifting out of control or washing ashore at points along Galveston Bay.

Later in the evening, the wind grew so intense that it peeled off the lighthouse’s heavy slate roof tiles. Eventually, some of the tiles shattered the lantern-room windows while the winds snuffed out the light for good. Anderson suffered serious facial wounds from flying glass shards. With no means of escape and the structure’s lowest level flooded, the elderly keeper and his wife rode out the storm in the parlor on the lighthouse’s main floor. It must have seemed strange to Anderson that in his second battle for survival on the Gulf Coast, his nemesis was Mother Nature and not a mortal enemy.

Across the ship channel at Bolivar Light, Harry Claiborne did his best to care for his flock. More than a hundred weary men, women, and children spent the stormy night inside the tower, seated on the spiraling steps leading up to the lantern room and the lamp. While he had food to give them, he had no fresh water. Claiborne tried to fill pails with rainwater from the gallery at the top of the tower, but the buckets filled only with wind-driven salt water. Amid the howling of the hurricane the tower occupants could hear big guns booming at nearby Fort Travis, on the Gulf side of Bolivar Point. Surrounded by floodwaters and defenseless against the storm’s fury, the fort’s trapped artillerymen were firing their batteries as a distress signal.

Aftermath of a Cataclysm

In the city, the wind began to moderate by 2300, allowing Root to return to the cutter by 0030 on Sunday morning with every member of his crew safe and sound and exhausted. And at about 0100, Haines’ lifeboat found the bottom. An hour later, the winds shifted to the south and died down to only 20 mph. The cloud cover cleared, and the moon illuminated the surroundings for the keeper and his surfmen. They had washed ashore a mile and a half beyond the normal shoreline, near Texas City, about nine miles northwest of the station. They walked to the nearest house, where they found two dozen storm survivors taking refuge.

At Bolivar Light survivors left the safety of the tower to find a scene similar to a battlefield. As the storm surge subsided, it left the lighthouse surrounded by the bodies of dozens who had failed to gain the safety of the structure before rising water sealed off its entrance. During the hurricane, Claiborne’s storm refugees had consumed all the provisions stored in the tower. And when he returned to his keeper’s quarters alongside the lighthouse, he found that the floodwaters had carried away or destroyed all of his household and worldly goods.

On Sunday morning, Colonel Anderson and his wife climbed the stairs to the Fort Point Lighthouse gallery, emerging arm-in-arm to survey the hurricane’s deadly toll. Dozens of human and animal carcasses drifted on the ebbing tide out of Galveston Bay to the Gulf of Mexico in a silent watery funeral procession. At nearby Fort San Jacinto, seawater had overwhelmed the fortifications and, in a matter of hours, wrought more destruction on the state-of-the-art defenses than an invading army. Only about 10 percent of the outpost’s 120 Army personnel survived. One of the soldiers rode out the storm perched on a wooden door that was blown all the way across Galveston Bay. When Anderson and his wife turned to locate the Fort Point Life-Saving Station, all they could see were four or five broken pilings where the buildings once stood.

At daylight, Haines and the two surfmen began searching the beach for survivors from the station. Within a mile, they found three more surfmen who had stayed alive by floating across Galveston Bay on flotsam. The three men recounted how the station building collapsed just after the lifeboat was swept away, setting them adrift. Haines divided his crew and began a systematic search along the beach, but found no trace of his wife or the last surfman.

The station keeper and his crew found shelter Sunday night on board the grounded Kendal Castle, which had finally come ashore at Texas City. On Monday the 10th, Haines secured a boat and crew at Galveston and rowed to Fort Point to survey the damage to his station and deliver badly needed supplies to Colonel Anderson and his wife at the lighthouse. Had Haines known that the pair would ride out the storm at Fort Point, he would have closed the nearby station early Saturday afternoon, but he believed the hurricane would destroy the lighthouse long before it swept away the lifesaving station. When he arrived, only the few torn pilings remained to indicate where his station once had stood.

For the next two weeks, Haines and his crew worked for Galveston’s relief committee locating hundreds of corpses, human and animal. In the rush to clear away the dead, most of the bodies were never identified and either buried (at sea or in the ground) or just burned where they lay. During this period, Haines retrieved the lifeboat that saved his life and found the station’s beach cart, Lyle gun, and surfboat. The surfboat had drifted to Hitchcock, Texas, 14 miles from Fort Point. Haines also located temporary graves containing the remains of his wife and the missing surfman, which had been found and buried on 10 September. On the 14th Haines and the crew rowed a boat carrying a casket to the temporary graves and retrieved Mrs. Haines’ body. It is not known whether the surfman’s remains were ever exhumed.

On board the Galveston, the ship’s carpenter and members of the crew set to rebuilding the exposed parts of the heavily damaged cutter. They patched holes in the small boats, mended the ship’s broken rigging, and replaced the windows and skylights shattered by wind and debris. Meanwhile, the rest of the crew towed countless human and animal carcasses out to open water. The tide returned many of them to Galveston Harbor, so the crew resorted to towing them to the nearby mud flats and burning them. The burial detail burned so many corpses that they finally ran out of combustible oil with which to immolate the bodies.

Devotion to Duty Remembered

The Coast Guard’s predecessor service personnel served valiantly in the Great Galveston Hurricane. They saved hundreds of lives at the cost of several of their own, including family members. For years, the U.S. Life-Saving Service boasted the unofficial motto of “You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.” This phrase refers to the many service personnel who went in harm’s way to save the lives of others. Edward Haines and the Galveston Life-Saving Station crew struggled mightily against the forces of nature at Fort Point. Aside from the loss of Haines’ wife and a surfman, two other surfmen were hospitalized because of serious injuries.

Members of the Lighthouse Service and Revenue Cutter Service demonstrated the same devotion to duty by manning the lights and rescuing storm survivors. Harry Clairborne saved scores of lives at the Bolivar Point Light, and the brave crew of the cutter Galveston put themselves in harm’s way to rescue victims in the city’s streets. The Treasury Department awarded the prestigious Gold Life-Saving Medal to Charles Root and James Bierman in recognition of their gallant conduct, and the Silver Lifesaving Medal to the other seven men in Root’s boat crew. The present-day Coast Guard recognized Harry Claiborne by naming one of its Keeper-class cutters, WLM-561, in his honor.

The 1900 hurricane devastated the Gulf Coast and left Galveston looking war-ravaged. Survivors and relief parties from across the country tried to rebuild the city, but it would never recover from the blow. Nearby Houston soon displaced it as the state’s primary port city. On 13 September 2008, history repeated itself when Hurricane Ike made landfall at Galveston. Modern weather forecasting and emergency-response systems helped limit casualties to approximately 135 killed—only a fraction of the losses suffered in the Great Galveston Hurricane.

Sources:

Annual Report of the Light-House Board, 1900, 1901, Department of the Treasury (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office).

Annual Report of the United States Life-Saving Service, 1908, Department of the Treasury (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office).

David L. Cipra, Lighthouses, Lightships, and the Gulf of Mexico (Alexandria, VA: Cypress Communications, 1997).

John, Coulter, ed. The Complete Story of the Galveston Horror, Written by the Survivors (United Publishers of America, 1900).

“High Praise Awarded by the Board of Investigation Appointed to Inquire into the Personnel of the Revenue Cutter Galveston,” Galveston Daily News, 2 October 1900.

“Imprisoned by the Storm: Thrilling Experience of Colonel Anderson, the Fort Point Lighthouse Keeper and His Wife—In the Face of Death the Light was Put Up—Isolated for Days in the Wrecked House without Supplies,” Galveston Daily News, 14 October 1900.

Record Group 26, “Journal of the United States Life-Saving Service, Galveston Station, District No. Nine (September 8–29, 1900),” National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

Erik Larson, Isaac’s Storm: A Man, a Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History (New York: Random House, 1999).

Paul Lester, The Great Galveston Disaster (Chicago: Monroe Book Company, 1900).

“Logs of Revenue Cutters and Coast Guard Vessels, 1819–1941,” Record Group 26, National Archives, Washington, DC.

“Special Report on the Galveston Hurricane of September 8, 1900 by Isaac M. Cline,” U.S. Weather Bureau.

U.S. Coast Guard Awards: Charles S. Root, James Bierman, USCG Historian’s Office, www.uscg.mil/history/awards/GoldLSM/8SEP1900.asp.

U.S. Coast Guard Cutters: Apache, 1891, ex-Galveston, USCG Historian’s Office, www.uscg.mil/history/webcutters/Apache1891.pdf.

U.S. Coast Guard Lightships: LV-28, USCG Historian’s Office, www.uscg.mil/history/weblightships/LV28.asp.