URGENT

FROM: COMMANDER YANGTZE PATROL

TO: COMMANDER IN CHIEF ASIATIC FLEET

13 DECEMBER 1937 10:03 AM

MESSAGE RECEIVED BY TELEPHONE FROM NANKING

PANAY BOMBED AND SUNK AT MILEAGE 221 ABOVE WOOSUNG. FIFTY-FOUR SURVIVORS. MANY BADLY WOUNDED . . . NAMES OF PERSONNEL LOST NOT KNOWN

This message announced an attack that could have triggered the start of World War II in 1937. What became known as the Panay Incident, in which Japanese forces repeatedly attacked an American gunboat in China, tested the national will of the United States at a time when isolationist sentiment at home was strong and tensions abroad high.

U.S. Presence in China Challenged

America’s military presence in China began in 1858 when rights to patrol the Yangtze River were arranged under the Sino-American Treaty. Its purpose was to protect U.S. personnel and interests, which steadily expanded into the 20th century. After the Spanish-American War, the U.S. Navy increased the number of gunboats available to patrol China’s rivers, and in 1901 the Yangtze Patrol became a subdivision of the Asiatic Fleet. According to a plaque in the wardroom of the USS Panay (PR-5), the patrol’s mission was “the protection of American life and property in the Yangtze River Valley . . . and the furtherance of American goodwill in China.” The gunboats were specifically prohibited from any offensive action.

Japan began to challenge American interests in China in 1900. That year Secretary of State John Hay had announced an Open Door policy with regard to China in order to establish American trade and a U.S. sphere of influence in the region. Japan responded by trying to extend its control throughout China.

Regional tension fluctuated for several years until 1931, when Japan invaded Manchuria to stifle rising Chinese nationalism and gain a source for raw materials. In essence, Japan annexed the area, renaming it Manchukuo. A Chinese plea for support from the League of Nations eventually resulted in the assembly condemning the invasion; Japan responded by withdrawing from the league. America was interested in recovering from the Great Depression, not in a “minor,” distant dispute. However, in 1932 President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt did reaffirm U.S. rights under the Open Door policy. Tokyo summarily rejected the policy as well as subsequent protests by declaring countries that did not recognize Manchukuo thereby forfeited economic privileges in the region.

A Neutral Gunboat Amid a War

In July 1937 Japan fabricated the Marco Polo Bridge incident near Peking to justify a full-scale invasion and occupation of China. On 29 July, Tientsin was bombed, and 13 days later Japanese marines landed in Shanghai. After attempts at finding a peaceful solution to the fighting failed, the United States decided to maintain its military forces in China to protect Americans.

By December the Japanese had advanced 200 miles and besieged Nanking, China’s capital. Japanese control of the lower Yangtze through Nanking would cut China in half and give the invaders excellent lines of communication and control of commerce. But Chinese military opposition exceeded Tokyo’s expectations, and Japanese attacks became more vicious, with no regard for civilian casualties. Although most foreigners had fled by this time, the Panay steamed from Chungking to Nanking to evacuate many of the few Americans remaining there.

Lieutenant Commander James Hughes, U.S. Naval Academy class of 1919, had assumed command of the Panay on 23 October 1936. As a result of the Japanese invasion, he had taken precautions, including having large U.S. flags painted on top of the gunboat’s fore and aft superstructure. A large American flag also flew at her stern. At night all of the flags were lighted so that they could be seen from shore and from above. Hughes also periodically informed the American consul general of the Panay’s exact location, information that was passed along to the Japanese to avoid an accidental attack on the gunboat.

By 11 December the situation in China had further deteriorated, and with the first artillery barrage on Nanking, the Panay got under way accompanied by three U.S. Standard Oil tankers. On board the gunboat were 14 mostly American civilian refugees—businessmen, diplomats, and journalists—as well as U.S. Army Captain Frank Roberts, a military attaché. As the group of ships moved upriver, one of the Panay’s civilians, Universal Newsreel cameraman Norman Alley, recalled, “All of us stood and watched the burning and sacking of Nanking until we had rounded the bend and saw nothing but a bright red sky silhouetted with clouds and smoke.”

Attacked from the Air and the River

At about 0930 on 12 December, a Japanese infantry detachment on shore signaled the Panay to stop. Commander Hughes complied, and soon after a motor launch came alongside the gunboat. A lieutenant, accompanied by four riflemen with fixed bayonets, came aboard and asked where the boat was going and why, and for locations of Chinese troops. The former queries were answered, but Hughes politely refused to answer the last one. The officer then asked to search the Panay and the tankers for Chinese troops, but again was refused. The commander closed the meeting by asking the party to leave his boat.

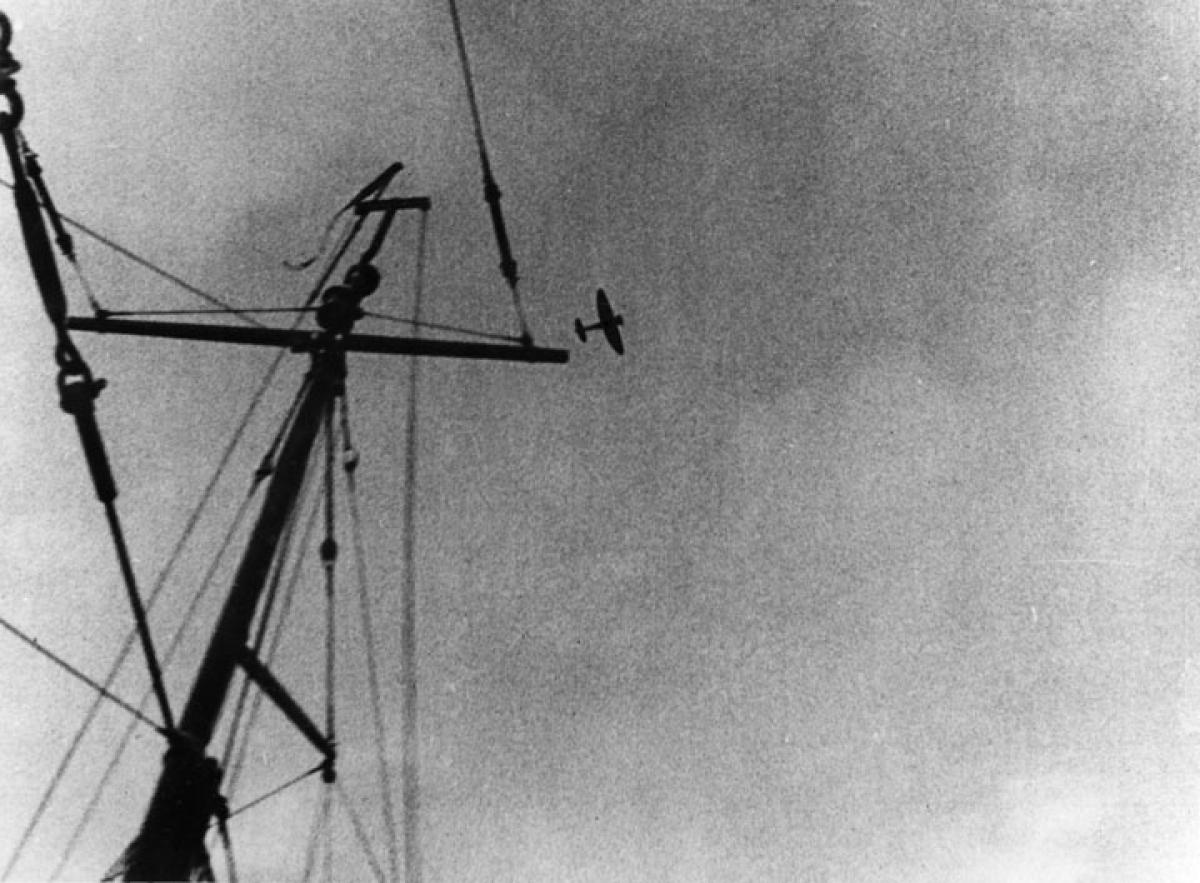

The Panay then continued upriver. At approximately 1330, when the vessels were about 27 miles from Nanking, approaching planes were heard high overhead. Suddenly, before a general alarm could be sounded, two tremendous bomb explosions erupted on board the Panay. One of the bombs had hit the port bow, disabling the 3-inch gun and severely injuring Captain Hughes. Meanwhile, near-misses rocked the boat and showered shell fragments across her decks. Alley later wrote: “My first reaction was that the Japanese, mistaking the Panay for an enemy ship had then realized their error and were leaving but this was wrong . . . as almost directly thereafter a squadron of six small pursuit-type bombers came over at a much lower altitude and immediately began to power-dive and release what seemed to be 100-pound bombs.”

More than 30 years after the event, Alley maintained that the Japanese attack was not a case of mistaken identity: “Hell, I can believe those babies flying level up there at 7,000 or 8,000 feet might not be able to tell who we were. But when they started dive-bombing, they would have had to see our flags. They came straight out of the sun. And they came over and over again.”

During the 30-minute attack, sailors manned the Panay’s machine guns to ward off the repeated bombing and strafing runs but failed to hit any aircraft. Damage to the Panay was extensive. She could not make steam, and there was flooding belowdecks. Unable to talk because of shrapnel wounds, the gunboat’s executive officer, Lieutenant Arthur Anders, finally wrote the order to abandon ship. Despite being strafed by Japanese planes, the Panay’s two motor launches made repeated trips to shore evacuating the crew and passengers.

By 1505, the sinking Panay had been abandoned—the first U.S. Navy ship ever lost to enemy aircraft. Casualties were heavy. Italian journalist Sandro Sandri, Lieutenant Edgar G. Hulsebus, and Storekeeper First Class Charles L. Ensminger were mortally wounded; 12 sailors, officers, and civilians were seriously injured; and 35 others sustained minor injuries. The Japanese also attacked and disabled the three Standard Oil tankers nearby, killing one civilian and injuring another.

As the last Panay personnel arrived on shore, Japanese patrol boats motored close to the stricken vessel from the direction of the launch that had approached the gunboat that morning. Soldiers on board the boats fired several machine-gun bursts at the Panay, which was still flying the American flag, before boarding her. Shortly thereafter the boats left, missing the disembarked sailors and civilians, who had hidden in tall reeds along the riverbank.

Leadership Tested

The injured Hughes passed command to Army Captain Roberts, the senior-ranking uninjured officer. Roberts, who fortuitously spoke fluent Chinese, proceeded to organize an escape plan while waiting for dusk. Chinese from a nearby town arrived and offered assistance. The survivors required help; 13 of the wounded needed stretchers, and two others had died. Captain Roberts mobilized the group, and it moved out to seek refuge in Chinese hamlets until telephone contact could be made with the U.S. ambassador to China, Nelson T. Johnson.

For almost 60 hours, the 70 men of the Panay successfully evaded the Japanese. At about 2000 on 14 December, a relief contingent of three British and American gunboats met the survivors on the Yangtze near Hohsien. Escorted by a Japanese destroyer, the relief column proceeded downriver until it rendezvoused with the USS Augusta (CA-31), flagship of Admiral Harry E. Yarnell and the Asiatic Fleet. Captain Roberts described the survivors’ arrival:

Past the devastation in Chaipei . . . we moved slowly around the point opposite Soochow Creek and came alongside the huge Augusta, her decks lined with sailors . . . there was no cheering: our flag was at half mast. Over a makeshift gangway, we clambered onto the flagship amidst flashes of news camera bulbs, passed along her board decks to Admiral Yarnell’s quarters to be greeted by the Admiral . . . and our own John Allison [U.S. consul in Nanking] who with tears in his eyes wrung our hands and thanked God we were safe. So did we all!

War or Peace?

An immediate concern was that the attack on the Panay would trigger a “Remember the Maine” reaction in the United States, resulting in war or retaliation. President Roosevelt responded with a formal protest to Tokyo on 13 December. Japan immediately made unofficial and private apologies and offered to meet all American demands. Stating that the attack had been a mistake, Japanese officials initiated an investigation. Minister of the Navy Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai reprimanded the squadron leaders of the attack, and Rear Admiral Teizo Mitsunami, head of Japanese naval air units in China, was relieved of command and ordered back to Tokyo. Their excuses and reasons for the attack were inconsistent.

The navy squadrons that attacked the Panay had been operating on intelligence provided by the army, whose response to the incident was indifferent. Army officials offered three baffling excuses:

• No Japanese patrol boats were in the area during the attack.

• The Panay provoked the incident by firing on Japanese soldiers with her 3-inch guns.

• Patrol boats never fired on the Panay.

In fact, the Japanese army and navy reacted differently to the incident, with each blaming the other. Although Admiral Mitsunami had been relieved, Japan did not identify another culprit.

That person could have been Colonel Kingoro Hashimoto, the senior commander of Japanese ground forces north of Nanking; he was known to be fanatically pro-army and anti-Western. Hashimoto had given orders to fire on any ships sighted on the Yangtze, and throughout the Nanking campaign his superior complained of his arrogance. The colonel, who had powerful political connections, was quietly recalled to Japan in 1938 but never otherwise disciplined. He continued to influence Japan’s war effort.

A Japanese army spokesman later confirmed that soldiers in a patrol boat had machine-gunned and boarded the Panay after she was abandoned. Furthermore, the War Ministry knew about that incident by 22 December 1937 but ordered all concerned personnel to remain silent. Perhaps the army deceived the navy into making the air attack on the pretext that the neutral ships were Chinese or contained Chinese soldiers; however, Masatake Okumiya, who commanded six dive bombers in the attack, denied that possibility.

Another possibility concerns the Japanese boarding party that visited the gunboat the morning of the attack. While Commander Hughes had answered most of the Japanese lieutenant’s questions, he had not allowed the party to search the Panay or the tankers and had ordered it off his boat. The boarding party’s report to local Japanese headquarters may have indicated it received a hostile reception and that perhaps the Americans were concealing something. The ranking officer in the area, Colonel Hashimoto, had authority to screen intelligence reports prior to submission to army headquarters.

A report on the encounter was sent to supreme army headquarters in China, and an air-operations staff officer there soon met with the headquarters’ naval-air liaison officer, Lieutenant Commander Takeshi Aoki. Aoki recalled the officer as saying: “According to the report of an advance Army unit, many Chinese troops are fleeing up the river from Nanking. They are on six or seven large merchant ships. Our ground forces can’t reach them now. So it is requested that the naval air arm make an attack at once.”

Aoki sent the request to the supporting naval air group, with the promise of a unit citation for a successful attack. By the time the squadron commanders and pilots received instructions, they had been filtered through at least eight people and were vague. The pilots scrambled into action, ignoring caution and probably misjudging the army’s report.

It is doubtful that Tokyo endorsed the attack; Japan still depended on America for raw materials in 1937. However, the military’s objective was the seizure of China, and an unchecked army dictated Japanese policy there, not Emperor Hirohito or the Diet.

The U.S. Navy Investigates

Speculation grew while observers and participants awaited the results of U.S. inquiries. The Panay’s survivors were certain the attack was deliberate. Perhaps local Japanese military authorities had decided to humiliate the United States and Great Britain. Four British gunboats and even the Augusta had been previous recipients of “stray” rounds.

Meanwhile, a naval board of inquiry had convened on board the Augusta. Among the 37 findings contained in its report, the panel determined that two distinct groups of aircraft had attacked the Panay. The first was the planes that initially bombed the gunboat. The second consisted of single-engine biplanes that dive-bombed and strafed the boat with machine-gun fire. The board reached four significant conclusions:

• Japanese aviators should have been familiar with the characteristics of the Panay, as she was present at Nanking during air attacks on the city.

• While the first bombers might not have been able to identify the Panay because of their altitude, attacking without properly identifying their target was inexcusable, especially since it was well known that neutral ships were on the Yangtze.

• It was “utterly inconceivable” that the Japanese dive bombers, which came within 600 feet of the Panay during attacks that lasted 20 minutes, could not have known the identity of the gunboat or the tankers they were attacking.

• The Japanese were “solely and wholly responsible for all losses which have occurred as the result of this attack.”

Apology Accepted and American Reaction

The United States received an official, “complete” Japanese apology on 24 December that blamed the incident on poor field communications and bad visibility. President Roosevelt accepted the apology but was nevertheless convinced that the attack was a deliberate attempt by Japan’s military to rid China of Western nations. Of particular concern to Roosevelt was Japan’s insistence that it was an accident. This position eliminated military responsibility and left the Japanese army unchecked in China. Similar attacks were still very possible.

Several months after the apology was received, the State Department gave the Japanese government an itemized claim for losses. On 30 April the Japanese Foreign Office presented the United States with a $2,214,007.36 check for property loss and death/personal injury indemnification.

Although the Panay Incident was officially closed, the attack had three major repercussions. First, the United States evacuated civilians from China and withdrew the Army’s 15th Infantry Regiment from Tientsin. The second aftereffect concerned isolationism and antiwar sentiment.

The Ludlow Amendment, originally proposed in 1935 by Representative Louis Ludlow of Indiana, sought to restrict a president and Congress from declaring war over isolated oversea incidents involving American nationals. The 1937 version of the bill specified that “except in the event of an actual invasion of the United States or its territorial possession and attack upon its citizens residing therein,” Congress’ authority to declare war would not become effective until confirmed by a majority of votes cast in a national referendum.

Immediately after the Panay attack, supporters of the legislation held the incident up as an example of how a president could push the country into war, and itbegan picking up widespread popular as well as congressional support. Significantly, the bill’s newfound momentum may have influenced President Roosevelt to soften the U.S. response to Japan. In Janaury 1938, an effort to release the measure from committee so it could be debated on the floor of the the House of Representatives was defeated by only 21 votes.

A final repercussion of the Panay Incident was that it made Roosevelt cognizant that world events were threatening American interests overseas. As a result, the president expanded military programs, especially within the Navy.

Roosevelt mustered sufficient political support while underscoring the defensive nature of naval expansion, and on 17 May 1938 Congress approved the Vinson Naval Bill. The legislation constituted the largest peacetime naval appropriation in history—more than $1 billion—and authorized construction of 46 combat ships, 26 auxiliary vessels, and 950 naval aircraft.

At the time, the Japanese attack on the Panay provoked conflicting reactions in the United States, stirring up both antiwar activists and saber-rattlers. But isolationism still held enough influence over foreign and military policy to prevent a strong U.S. reaction. However, four years later when Japanese aircraft again attacked the U.S. flag there would be no national doubt or unwillingness to declare war.

Iris Chang, The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II (New York: Penguin Books, 1997).

“Recipients of the Navy Cross,” www.homeoftheheroes.com.

Manny Koginos, The Panay Incident: Prelude to War (Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1967).

Masatake Okumiya, “How the Panay Was Sunk,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 79, no. 6 (June 1953).

USS Panay Memorial Website, “The Crew,” www.usspanay.org/crew.shtml.

Hamilton D. Perry, The Panay Incident: Prelude to Pearl Harbor (Toronto: Macmillan Company, 1969).

MGEN Frank N. Roberts, U.S. Army (Retired), “The Panay Incident,” unpublished personal narrative, 1938, in author’s possession.

Barbara W. Tuchman, Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911–1945 (New York: Macmillan, 1970).