Orville and Wilbur Wright developed the principles of manned, powered flight, first demonstrated on 17 December 1903, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, with their Wright Flyer. But it was Glenn Hammond Curtiss who in large measure was responsible for the “selling” of aviation by putting his early flying machines to practical use.1

In 1908, 30-year-old Curtiss designed, built, and flew his own airplane. He won nationwide attention in May 1910 by capturing the New York World’s $10,000 prize for being the first aviator to fly from Albany to New York City. He made the 1421/2-mile trip in 2 hours, 50 minutes. Somewhat prematurely, the World claimed: “The battles of the future will be fought in the air! The aeroplane will decide the destiny of nations.”

The newspaper promptly set up a “bombing range” on Keuka Lake at Hammondsport, New York, near Curtiss’ shop, arranging floats to simulate the 500-by-90-foot outline of a battleship. Curtiss flew over in his airplane and dropped 8-inch lengths of 11/2-inch-diameter lead pipe on the “battleship.” Rear Admiral William W. Kimball, one of the observers, dismissively declared: “There are defects for war purposes: lack of ability to operate in average weather at sea; signalling its approach by noise of motor and propellers; impossibility of controlling its height and speed to predict approximate bombing ranges; difficulty of hitting from a height great enough to give a chance of getting within effective range.”

The press interpreted the results differently. The World told of “an aeroplane costing a few thousand but able to destroy the battleship costing many millions.” The New York Times acknowledged a new “menace to the armored fleets of war.” The aircraft-versus-battleship controversy was raging before the Navy had purchased its first aircraft. At the time the U.S. Army had only one Wright flying machine.

On 26 September 1910—one year after the Army had bought that first aircraft—Captain Washington Irving Chambers, assistant to the Secretary of the Navy’s aide for matériel, was directed to keep the Navy informed of aviation matters. Chambers, who had just completed a tour of duty as commanding officer of the battleship Louisiana, was interested in engineering and considered to be an aggressive officer. Much to the benefit of the Navy, he soon became very interested in aviation.

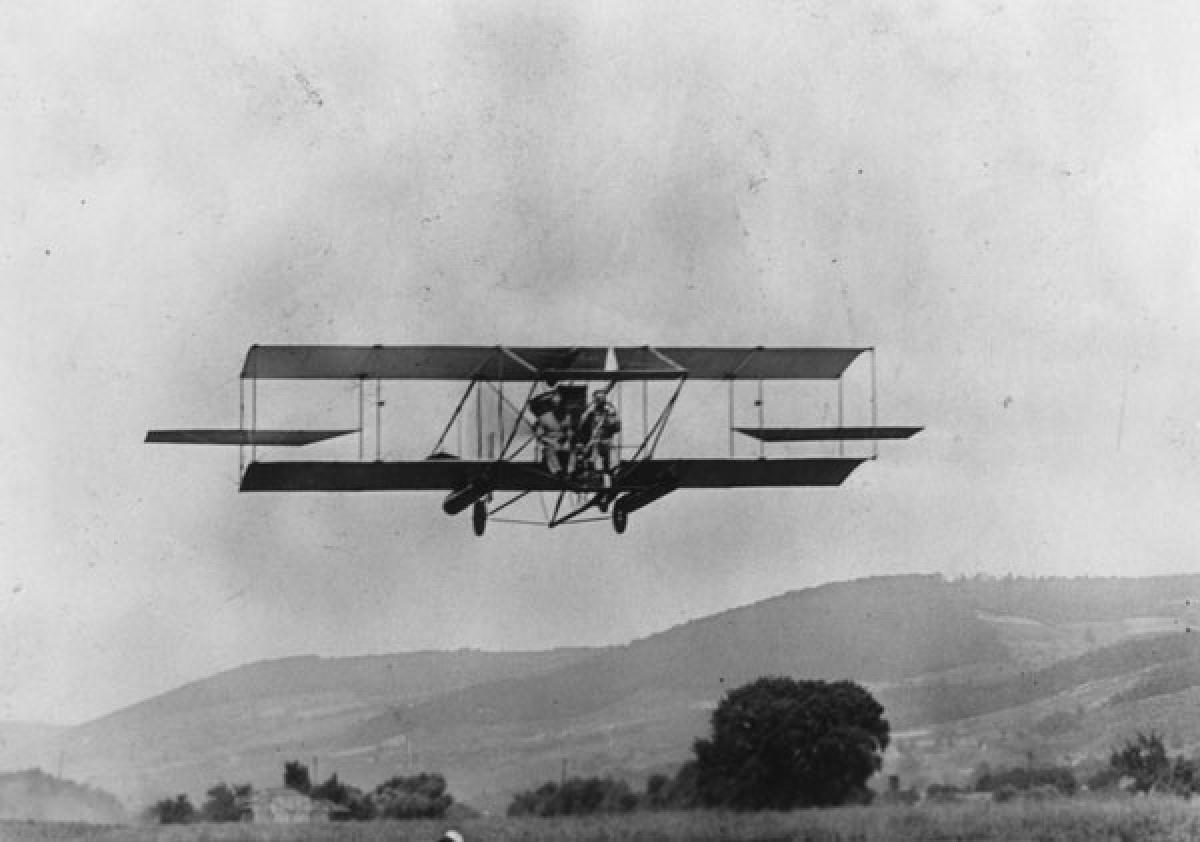

Under Chambers’ direction, Glenn Curtiss provided an aircraft for two historic firsts—the first takeoff of an aircraft from a ship, from the scout cruiser Birmingham on 14 November 1910, and the first shipboard landing, aboard the larger armored cruiser Pennsylvania on 18 January 1911. Both flights were made by Eugene Ely, a Curtiss test pilot, in the same Curtiss pusher aircraft.

The year 1910 had ended on another bright note for naval aviation when, on 23 December, the Navy took up an offer by Curtiss to teach, without charge, a naval officer to fly. Lieutenant Theodore G. Ellyson reported for flight training to the Curtiss camp at North Island (San Diego), California. The following March the Wright Brothers offered to train a pilot for the Navy contingent upon the purchase of one airplane for $50,000. When the Wrights made their offer unconditional, the Navy ordered Lieutenant John Rodgers to the Wright training camp for instruction; he become the U.S. Navy’s second aviator.

Captain Chambers negotiated for the purchase of three aircraft for a total of $25,000—two from Curtiss and one from the Wrights. Curtiss was favored because of his early interest in seaplanes and his flight with one of his aircraft that alighted near the Pennsylvania, anchored off San Diego, on 17 February 1911. While hundreds of Sailors lined the rail to watch, the aircraft was hoisted aboard the ship and then returned to the water, and Curtiss took off.

On 1 July 1911, the Navy’s first aircraft, the Curtiss A-1 Triad hydroaeroplane, or seaplane, became airborne with Curtiss himself at the controls. The pusher-engine biplane, powered by a 75-horsepower Curtiss V-8 engine, was fitted with a combination of wheels and a large, single float. The name Triad was derived from its three capabilities—land, sea, and air. The aircraft took off from and landed on Keuka Lake. The A-1’s first flight lasted five minutes and reached an altitude of 25 feet. A total of three flights was made on that date—one by Curtiss with Ellyson as a passenger and two by Ellyson alone.

The Navy’s second aircraft, a wheeled landplane, the Curtiss A-2, flew for the first time at Hammondsport on 13 July. Curtiss was again at the controls for its first flight. Beyond these early flights, Ellyson used his time at Hammondsport making night takeoffs and landings on the lake, and takeoffs from an inclined launching wire rigged from the beach down to the water. (The Navy accepted the Wright B-1 landplane at Dayton, Ohio, in 1912.)

Subsequently, the fledgling naval air arm was moved to Greenbury Point, across the Severn River from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. But late in the year naval aviation was moved from Annapolis to San Diego on land owned by Curtiss.2

The A-2 was rebuilt as a hydroaeroplane, while Curtiss delivered two additional aircraft of the type to the Navy, the A-3 and A-4. On 6 October 1912, Lieutenant John Towers (Naval Aviator No. 3) piloting the A-2 remained aloft for 6 hours, 10 minutes, setting an American endurance record. Beginning on 12 November 1912, the A-3, piloted by Ellyson, was used in catapult trials at the Washington Navy Yard. The same aircraft also established an American altitude record for seaplanes, 6,200 feet.

The Navy Department was obviously pleased with the Curtiss-built aircraft, for 19 of the Navy’s first 26 aircraft were produced by Curtiss; 2 were Burgess Co. & Curtis (no relation to Curtiss) flying boats; 2 were Burgess-Dunne hydroaeroplanes; and only 3 were Wright aircraft (delivered in 1912–13).

In future years Curtiss would produce many naval aircraft. Among the most noteworthy were his large World War I–era flying boats, typified by the H-16. The later, even larger NC-series flying boats were developed for long-range operations against U-boats and were capable of flying to Europe with intermittent stops. In May 1919, the NC-4 was the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, albeit in stages. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels later wrote of the NC-4 flight, “It will rank with the laying of the Atlantic cable and other events which have marked a distinct and significant advance in the history of the mastery of the elements by man.”

Other notable Curtiss aircraft were the JN-series biplane trainers, the F9C Sparrowhawk airship-borne fighters, the SBC and SB2C Helldiver dive-bombers, SOC Seagull scout-observation floatplanes, and R5C Commando transports. While later Curtiss aircraft, which were produced through 1947, did not achieve eminence, Curtiss did provide the U.S. Navy with many notable—and its first—aircraft.

1. Curtiss aircraft are best described in Peter M. Bowers, Curtiss Aircraft 1907-1947 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1979), and Gordon Swanborough and Peter M. Bowers, United States Navy Aircraft since 1911 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1976), pp. 91-154, 424-428.

2. Subsequently, naval aviation moved back to Annapolis and then, in January 1914, to Pensacola, Florida.