President Abraham Lincoln was in a somber mood on 8 July 1862 when he visited Harrison's Landing on the James River in Virginia, where the USS Galena lay anchored.

Less than two months before, on 15 May, the Galena had been the lead vessel of a Union naval squadron ordered to steam up the James, disable Confederate batteries along the shoreline, and bombard Richmond into submission. But the fleet never got past Fort Darling, situated on Drewry's Bluff, some eight miles below the Rebel capital. Confederate artillerists and sharpshooters unleashed a barrage of shot, shell, and lead, compelling the Galena and her support vessels to withdraw.

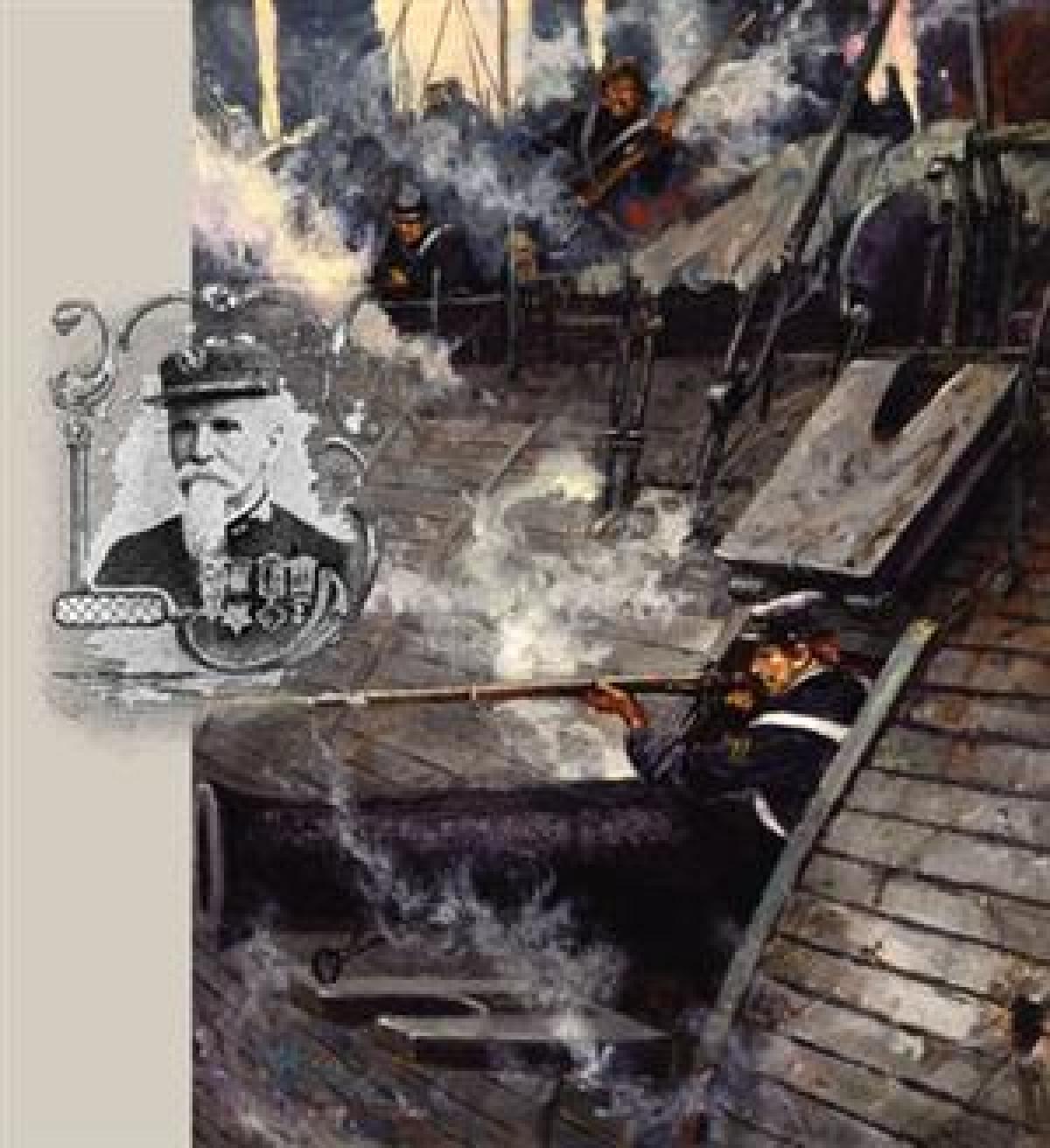

The Galena had taken the worst of it. After Lincoln and his entourage boarded the ship and inspected the damage, the President turned to the assembled crew and remarked, "I cannot understand how any of you escaped alive." He then delivered a short speech, thanking the officers and men "for their magnificent service."1

The Young Heroes'

Three crew members were singled out for special recognition. The captain of the Galena, Commander John Rodgers Jr., called on them to step forward: Marine Corporal John F. Mackie, Quartermaster Jeremiah Regan, and First-class Fireman Charles Kenyon. "Mr. President," Rodgers announced, "these are the young heroes of [the] Fort Darling battle."

Lincoln approached each of them, shook hands, and thanked them "for their gallant conduct." He then turned to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and ordered that the men receive a promotion and the Medal of Honor.2

Little did those on deck realize that this was a singular moment. It was the first and only time that a President of the United States (rather than an officer) recommended combatants for this highest military award. For John Mackie it was a double distinction; not only did he receive the medal at the behest of the commander-in-chief, but he was also the first U.S. Marine to be so honored.

Yet there was more than a twist of tragic irony to the event. The Battle of Drewry's Bluff, as it became known, where Mackie demonstrated bravery well beyond the call of duty, was the only engagement in the history of the Corps where U.S. Marines and former Marines met in direct combat.

Of course, it was only a matter of time until such a clash would unfold. Once the states of the deep and upper South left the Union during the secession crisis of 1860-61, like the other military services, the U.S. Marine Corps suffered its share of defections. In sheer numbers, however, the resignations were few compared to the Army and Navy, if for no other reason than the Corps itself was the smallest branch of the U.S. military. Its prewar strength was around 1,800 men, a little more than 10 percent the size of the Army and 20 percent of the Navy.3

Confederate Marine Corps

Despite its slim numbers, the Corps was hit hard. While few enlisted men quit, this was not the case in terms of officer defections, especially on the junior level. For whatever reason, the states of the upper South were a primary source of Marine officers, and once the states severed bonds with the Union, most of their native sons followed suit. Nearly one-third (20 of 63) of its officers left. Of those, 19 served as the principal architects and leaders of the newly created Confederate States Marine Corps.

The Corps lost some of its most promising and brightest officers, many from Virginia. First Lieutenant Israel Greene was perhaps the best known at the time because he had led the Marines who subdued John Brown and his followers in 1859 at Harpers Ferry. Another son of the Old Dominion, Captain George H. Terrett, had distinguished himself at the battle of Chapultepec in the Mexican War. And still another Virginian and hero of Chapultepec was First Lieutenant John D. Simms, who, along with First Lieutenant Julius E. Meiere of Maryland, would see action at the Battle of Drewry's Bluff.4

Defections notwithstanding, the role Marines played in the Civil War would be the same as it had been since the creation of the Corps in 1798. Unlike 20th- and 21st-century Leathernecks, who would serve (and continue to serve) on extended expeditionary missions or as amphibious strike forces, 19th-century Marines functioned primarily as an arm of the Navy. Whether it be ashore or afloat, Marines performed a variety of tasks, such as guarding shipyards, enforcing shipboard discipline, serving on deck as sharpshooters, repelling boarders, manning guns on ships, and occasionally joining landing parties for brief operations ashore.5 In fact, if Union commanders had recognized the tactical import of this last role, the outcome at Drewry's Bluff might have been different.

There were indeed a number of "might-have-beens" regarding Union operations in the spring of 1862. If, for example, Major General George B. McClellan, at the head of a 100,000-man army on the Virginia Peninsula between the York and James Rivers, had not spent most of April in an unnecessary siege at Yorktown, but instead chose to conduct a rapid 70-mile march up the peninsula, he might have taken Richmond. The delay allowed Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston to move his forces into position to oppose a Union advance.6

After finally taking Yorktown on 4 May, McClellan, nicknamed the "Virginia Creeper" for his geophysical pace, inched slowly toward Richmond. As Confederate troops withdrew to protect their capital, the Rebel-held Norfolk Navy Yard had to be abandoned. Retreating Southerners blew up or set fire to everything of military value, including the famous (or in Union eyes, the infamous) CSS Virginia, which had engaged the USS Monitor in the historic battle of ironclads at Hampton Roads, Virginia, two months before. Without a supply base for the ship and unable to lighten her draft to get up the James River to help defend Richmond, the Confederates had no choice but to destroy the vessel rather than allow her to fall into enemy hands. On the morning of 11 May, after the crew removed the Virginia's guns, they set her on fire, a blaze that eventually reached the magazine and blew the ironclad to bits.7

Up the River

The Union Navy then swung into action. With the Virginia's destruction, the James River was left virtually defenseless. Given the problems McClellan was encountering (or creating for himself) on land, why not attack Richmond by water? That was precisely what Secretary of the Navy Welles had in mind when he telegraphed Flag Officer Louis R. Goldsborough to send a Union squadron up the James straight to the Rebel capital.8

The squadron was composed of five ships, led by the Galena. Named in honor of then-Major General Ulysses S. Grant's hometown in Illinois, the Galena was armed with six guns, her sides protected by horizontally laid interlocking iron plating some three inches thick. Her captain, Commander Rodgers, a veteran officer and member of one of the most celebrated families in American naval history, was in charge of the task force, which included two other ironclads, the Monitor and Naugatuck, and two wooden gunboats, the Port Royal and Aroostook.9

With Rodgers in command, the Monitor as part of the flotilla, and the Virginia no longer a threat, victory, it seemed, was within the Union's grasp. So thought U.S. Marine First Lieutenant William H. Cartter. Writing to his mother from Hampton Roads on 11 May, Cartter predicted, "Richmond will be ours" within the next day or so. "The game is nearly up with them. I am in hopes that we shall start for home soon. . . ."10

A bit more guarded in his optimism, Flag Officer Goldsborough nevertheless was also of the opinion that Rodgers and his squadron would have an easy time of it. Despite reports that the Rebels were placing obstructions in the river, since they were put down "very hurriedly," Goldsborough was convinced that "there will be no great difficulty . . . in clearing a passageway."11

Rebel Capital in Danger

Richmond was in a state of panic. Though Confederate President Jefferson Davis, with military adviser General Robert E. Lee at his side, told his cabinet that Richmond would be held at all cost, plans were under way for evacuation. The Confederate treasury's gold supply was packed and ready for shipment on board a waiting train, while the government had already sent its records to Columbia, South Carolina.12

But all was not yet lost. The Rebels were planning a last ditch stand at a site on the James River—Drewry's Bluff. Additional artillery, reinforcements, and river obstructions were being put into place there to challenge the Union flotilla and prevent it from steaming up the James and shelling Richmond.

As things turned out, the Confederates could not have chosen a better defensive position. The bluff, named after its wealthy owner, Captain Augustus H. Drewry, was about 100 feet above the water on a sharp bend in the river. From that vantage point, Confederate gunners had an unobstructed line of fire for more than a mile in both directions. A local artillery company under the command of Captain Drewry originally had manned the bluff (officially known as Fort Darling). But once those in Richmond grasped its potential, preparations got under way to create a "Gibraltar of the South."13

General Lee dispatched several infantry units, a company of sappers and miners, and a battalion of artillery, led by former U.S. Marine Colonel Robert Tansill, who oversaw the emplacement of three additional heavy guns. At the same time, the crew of the Virginia (elated that they would have another opportunity to do battle with their nemesis, the Monitor) had arrived in the area. The men would man the cannon on the opposite side of the James (the north bank) known as Chaffin's Bluff, a mile and a half from Drewry's Bluff. In this thickly wooded area, the Virginia's Marine detachment (more than 50 strong) would serve as sharpshooters, picking off any exposed Union Sailors above or below decks.14

Another Confederate Marine unit—a battalion of two 80-man companies under Captain John D. Simms—occupied the south bank on the Drewry's Bluff side. Simms, a 20-year veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps, had tendered his resignation with much reluctance. One of his company commanders, First Lieutenant Julius E. Meiere, was also a former U.S. Marine officer, whose wedding President Lincoln and Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois had attended. Despite a promising career, Meiere, who had married a Southern belle, left the Corps and offered his services to the Confederacy.15

With anywhere between 8 to 14 guns in place (the number is in dispute) and more than 200 Confederate Marines in rifle pits on both sides of the river, the Rebels were hopeful that the Union task force could be stopped. And if all else failed, the obstructions placed in the river—pilings, cribs of stone, and sunken canal boats and steamers (including the scuttled gunboat Jamestown)—placed just below the bluff, made it virtually impassable without a massive clearing effort.16

Undaunted, the Union flotilla steamed up the James. Its commander, John Rodgers, planned to unleash the firepower of his flagship, the Galena, against the Confederate defenders, while the rest of the expedition slipped by and headed for the wharves of Richmond. After all, only three weeks before, the Union Navy's Rear Admiral David G. Farragut had implemented a similar strategy on the lower Mississippi against Rebel batteries defending New Orleans, and it had proved successful. Rodgers, however, was destined to be disappointed—but not for lack of trying.

Maneuvering the Flotilla

At around 0630 on Thursday, 15 May, the Galena, followed by the Monitor, Aroostook, Port Royal, and Naugatuck, came within view of the Confederate defense works at Drewry's Bluff. As planned, Rodgers ran the Galena within 600 yards of the enemy position, and, despite the narrowness of the channel (it was no more than twice as wide as the ship itself), he was able to position the vessel perpendicular to the flow of the river and bring her guns to bear on the Rebel artillery emplacements.

Though impressed with Rodgers' nautical skills (one Confederate onlooker later wrote that "it was one of the most masterly pieces of seamanship of the whole war"), the Southerners lost no time in firing the first rounds. The Galena responded in kind, and the fate of Richmond, less than eight miles away, with its windows rattling from the roar of the cannon, stood in the balance.17

For the next several hours, the Confederate Marines and other Rebel riflemen on both banks of the river sniped at the Union crewmen whenever they showed themselves on deck (or even below when exposed through gun ports), while the artillery gunners on the bluff unleashed a barrage of shot and shell, much of it targeting the Galena. Other ships in the Union task force that attempted to come to her aid were quickly eliminated from the action. The Naugatuck's main gun malfunctioned, compelling the vessel to withdraw. Confederate shells hit both the wooden gunboats, the Port Royal and Aroostook, forcing them to retreat downstream as well. At one point in the battle the Monitor passed above the Galena, hoping to shield her and at the same time shell the Rebel positions. But her guns could not be elevated enough to reach the top of the bluff. Like the others, the Monitor had no choice but to drop back.

The Galena, however, refused to back down and made a fight of it, hammering the enemy's gun emplacements with explosive shells, and silencing at least two of them. Nevertheless, it was only a matter of time before the ship's Achilles' heel became apparent. Unlike the Monitor's thick iron sheathing, which was able to repel the Confederate shot, the armor plating affixed to the Galena proved too thin to protect her from the merciless hail of fire.18

A Perfect Slaughterhouse'

In his postbattle report, Commander Rodgers noted with considerable understatement that the Galena was "not shot proof: balls came through and many men were killed with fragments of her own iron." The ship's assistant surgeon described the scene as "[a] perfect slaughterhouse." The Rebels "poured into our sides a shower of solid shot and rifled shell, many of which came through our mail [armor] as if it had been paper, scattering our brave fellows like chaff."19

With nearly a quarter of her crew wounded or killed, the Galena stubbornly held her position, in part thanks to her 14-man Marine detachment. Throughout the battle, the ship's Marines were firing their muskets from the deck and through gun ports at their Confederate counterparts on shore. Return fire from the Rebel Marines must have been intense. When a port cover on the Galena jammed and a Yankee Sailor exposed his arm to shake it loose, a burst of rifle shots from the bushes rang out, and the arm dropped into the water.20

Then came "the decisive moment of the action," as a Marine on the Galena later put it. Three rounds, one after the other, crashed into the vessel, two of which passed "completely through her thin armor."21 The gun deck below was a horrific sight, according to William Keeler, the Monitor's assistant paymaster, who went on board the Galena immediately after the battle.

Here was a body with the head, one arm & part of the breast torn off by a bursting shell—another with the top of his head taken off the brains still steaming on the deck, partly across him lay one with both legs taken off at the hips & at a little distance was another completely disemboweled. . . . [The deck was] covered with large pools of half coagulated blood & strewn with portions of skulls, fragments of shells, arms, legs, hands, pieces of flesh & iron, splinters of wood & broken weapons were mixed in one confused, horrible mass.22

With several gun crews decimated and their guns rendered inoperable, Marine Corporal John F. Mackie, a 26-year-old silversmith from New York City, "seized the opportunity" and shouted to his comrades, "Come on, boys, here's a chance for the Marines!" Mackie and his men removed the wounded, threw sand on the gun deck, "which was slippery with human blood," and got the heavy guns at work once again. "Our first shots," Mackie recalled with pride, "blew up one of the [Rebel] casemates and dismounted one of the guns that had been destroying the ship."23

Mackie and his fellow Marines manned the guns until word was passed that the ammunition was nearly expended. Around 1130, after almost four hours of continuous combat, Commander Rodgers ordered a halt to the action and a withdrawal.

Richmond breathed a sigh of relief. True, the Rebel capital was not out of the woods yet. McClellan's army was still advancing along the York River on the other side of the peninsula, but the general's ponderous movements and dilatory tactics would prove fruitless in the end.

Aftermath on the Galena

As for the repulsed Union flotilla, the Galena had withstood the worst of it, sustaining 43 hits, of which 13 shots penetrated her armor, with one passing entirely through the ship. In view of the scope and scale of the damage, it is incredible that the human cost was not heavier: 13 killed (including one Marine) and 11 wounded. Yet despite the structural damage and human carnage, the Galena somehow managed to inflict casualties on the victorious Confederates: seven dead, eight wounded.24

In the aftermath of the battle, leaders on both sides realized how easily the outcome could have been different. As several Confederate officers later observed, if Union troops, acting in concert with the ironclads, had attacked the stronghold, they could have taken Drewry's Bluff and cleared a path to Richmond. Commander Rodgers agreed. It was "impossible," he concluded, "to reduce such works except by the aid of a land force."25

Actually, the Union had created a special amphibious Marine battalion in the autumn of 1861, but it never made a combat landing. Its officers feared that if the Corps engaged in such tactical actions, it would eventually merge with the Army and lose its identity.

Whatever the case, those Marines who fought at Drewry's Bluff distinguished themselves all the same. In his official report, Rodgers maintained with his usual understatement that, "the Marines were efficient with their muskets, and . . . when ordered to field vacancies at the guns, did it well."26

Captain Simms, who had commanded the Confederate Marines defending the bluff, also praised his men. As he reported a day after the battle:

I stationed my command on the bluffs some two hundred yards from them [the Union flotilla] to act as sharpshooters. We immediately opened a sharp fire upon them, killing three of the crew of the Galena certainly, and no doubt many more. The fire of the enemy was materially silenced at intervals by the fire of our troops. It gives me much pleasure to call your attention to the coolness of the officers and men under the severe fire of the enemy.27

That Marines on both sides acquitted themselves with honor is beyond question. Yet it was a peculiarly tragic sense of honor when American Marines fought each other rather than an external foe. Fortunately, the Battle of Drewry's Bluff was unique. While U.S. Marines and former U.S. Marines would participate in other battles—Mobile Bay, Savannah, Fort Fisher, to name a few—none would place them in direct confrontation as had occurred on that bloody Thursday morning in mid-May 1862.

1. Walter F. Beyer and Oscar F. Keydel, Deeds of Valor: How America's Heroes Won the Medal of Honor (Detroit: The Perrien-Keydel Company, 1902), vol. II, pp. 29-30.

2. Ibid. See also Frank H. Rentfrow, "On to Richmond," The Leatherneck, January 1939, pp. 10-11; David M. Sullivan, The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War—The Second Year (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Company, Inc., 1997), p. 35.

3. Sullivan, The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War, p. xi; Allan R. Millet, Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1980) p. 88.

4. Ralph W. Donnelly, The Confederate States Marine Corps: The Rebel Leathernecks (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Company, Inc., 1989), pp. 170-71, 173; J. Robert Moskin, The U.S. Marine Corps Story (New York: McGraw -Hill Book Company, 1987), p. 78; Joseph H. Alexander, The Battle History of the U.S. Marines: A Fellowship of Valor (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1997), p. 16.

5. Millet, Semper Fidelis, pp. 91-91; Donnelly, Confederate States Marine Corps, p. 270; Jeffrey T. Ryan, "Some Notes on the Civil War Era Marine Corps," Civil War Regiments: A Journal of the American Civil War, II (1992), p. 189.

6. James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 424-27; Spencer C. Tucker, Blue & Gray Navies: The Civil War Afloat (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2006), pp. 175-77.

7. Edwin C. Bearss, River of Lost Opportunities: The Civil War on the James River, 1861-1862 (Lynchburg, VA: H. E. Howard, Inc., 1995), p. 42; William C. Davis, Duel Between the First Ironclads (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1975), pp. 152-54; William M. Robinson, Jr., "Drewry's Bluff: Naval Defense of Richmond, 1862," Civil War History, VII (June 1961), pp. 170-71.

8. Bearss, River of Lost Opportunities, pp. 42-43; Robinson, "Drewry's Blufff," pp. 172-73; John M. Coski, Capital Navy: The Men, Ships, and Operations of the James River Squadron (Campbell, CA: Savas Woodbury Publishers, 1996), pp. 37-38.

9. Harper's Weekly, 5 April 1862; Kurt Hackemer, "The Other Union Ironclad: The USS Galena and the Critical Summer of 1862," Civil War History XL (September 1994), pp. 227-30; David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History (Santa Barbara, CA: 2000), IV, p. 1669; Tucker, Blue & Gray Navies, pp. 36-37, 178-79.

10. Sullivan, United States Marine Corps in the Civil War—Second Year, p. 30.

11. U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894-1927), Series I, Vol. 7, p. 355 (hereafter cited as ORN).

12. Virgil Carrington Jones, The Civil War at Sea: March 1862-July 1863 (New York: Holt, Rinehart, Winston, 1961), II, pp. 34-35; Bearss, River of Lost Opportunities, p. 56.

13. Robinson, "Drewry's Bluff," pp. 167-68; Coski, Capital Navy, pp. 39-40; Hackemer, "The Other Union Ironclad," pp. 232-33.

14. Bearss, River of Lost Opportunities, pp. 48-51; Sullivan, United States Marine Corps in the Civil War—The Second Year, p. 31; Donnelly, Confederate States Marine Corps, p. 212; Tucker, Blue & Gray Navies, pp. 179-80.

15. Coski, Capital Navy, pp. 111-12; Bearss, River of Lost Opportunities, pp. 51, 54; Donnelly, Confederate States Marine Corps, p. 209.

16. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing office, 1880-1901), Vol. XI, Part I, p. 636 (hereafter cited as OR).

17. Coski, Capital Navy, pp. 43-44; Sullivan, United States Marine Corps in the Civil War—The Second Year, p. 32; Robinson, "Drewry's Bluff," pp. 173-74; Tucker, Blue & Gray Navies, p. 180.

18. Beyer and Keydel, Deeds of Valor, 26-27; ORN, Series I, Vol. 7, p. 357; Hackemer, "The Other Union Ironclad," pp. 235-37.

19. ORN, Series I, Vol.7, p. 357; Hackemer, "The Other Union Ironclad," pp. 238-39.

20. Jones, The Civil War at Sea, II, p. 38; ORN, Series I, Vol. 7, p. 370; Robert W. Daly, ed., Aboard the USS Monitor, 1862: The Letters of Acting Paymaster William Frederick Keeler, U. S. Navy to his wife, Anna (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1964), p. 126; Beyer and Keydel, Deeds of Valor, p. 26.

21. The Story of American Heroism: Thrilling Narratives of Personal Adventures During the Great Civil War as told by the Medal of Honor Winners and Roll of Honor Men (Philadelphia, PA: B. T. Calvert & Co., 1897), p. 658.

22. Daly, Aboard the USS Monitor, p. 130.

23. The Story of American Heroism, pp. 654, 658; Beyer and Keydel, Deeds of Valor, p. 28.

24. ORN, Series I, Vol. 7, pp. 357, 359, 370; Sullivan, United States Marine Corps in the Civil War—The Second Year, pp. 37-38.

25. New York Herald, 19 May 1862; Bern Anderson, By Sea and By River: The Naval History of the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962), pp. 82-83; Beyer and Keydel, Deeds of Valor, p. 25; OR, Series I, Vol. XI, Part I, p. 636; ORN, Series I, Vol 7, p. 362.

26. ORN, Series I, Vol. 7, pp. 368-69.

27. Donnelly, Confederate States Marine Corps, p. 42.