For Captain John Barry of the Continental Navy, 1777 was ending as it had begun—on horseback.

The earlier equestrian trip came at a more hopeful time, both for himself and his young country. In early April 1776, as captain of the brig Lexington, the Irish-born Barry had captured the British tender Edward, one of the first Royal Navy ships taken by the Continental Navy. He and other officers and Sailors later joined John Cadwalader's Pennsylvania Brigade and fought at the 3 January 1777 Battle of Princeton, the follow-up win to the more famous victory at Trenton. Afterward, Barry rode back to the American capital of Philadelphia to resume overseeing the construction of his new command, the frigate Effingham.1

General George Washington and his Continental Army also moved south that year to defend the capital from a combined British offensive led by General Sir William Howe and his brother, Admiral Lord Richard Howe. While Sir William earned victories at Brandywine and Germantown, Lord Richard captured the Delaware River strongpoint of Fort Mifflin, and the Americans soon abandoned nearby Fort Mercer. After withdrawing from Philadelphia, which the British had occupied in September, Washington and the remnants of his army set up winter quarters at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. The Continental Congress, meanwhile, fled to York, about 75 miles west of Philadelphia.

The British successes put Barry's career in jeopardy. With the capture of Philadelphia, he was ordered to sail the Effingham up the Delaware to White Hill, accompanied by the Washington under Captain Thomas Read. The latter ship's namesake, as commander of both army and naval operations, ordered both frigates sunk in a manner that would allow the Americans to later refloat them.2 The order galled the two captains but was approved by the Continental Navy Board of the Middle Department, then in nearby Bordentown, New Jersey. A board member, Francis Hopkinson, chose to personally supervise the operation.

Ensuing discussions between Barry and Hopkinson were acrimonious at best. When the civilian assumed command, he gave the order to pull the ships' plugs as the tide was running out, not in. Water rushed into the Effingham so quickly she began goind down on her beam ends. Realizing what was about to happen, Hopkinson got off the sinking frigate and slunk off to headquarters. Barry's attempts to raise his ship failed. His subsequent return to Bordentown coincided with the arrival of 300 cold and hungry sailors from the Pennsylvania Navy, their ships burned. Barry visited Hopkinson in "a fine fit of Irish temper," and the board member responded in kind.3

A Little Ruse

Frustrated by inactivity, Barry went over Hopkinson's head and wrote to the Marine Committee of Congress, asking and receiving Christmas leave to visit his bride in Reading. The captain, however, had a hidden agenda. He wanted to discuss a plan with Washington, but not Hopkinson, and headed to Reading by way of Valley Forge.

His departure from Bordentown did not go unnoticed. Furious, Hopkinson wrote a letter to the Marine Committee detailing Barry's insubordination.4 Hopkinson did not send the report to York, but to committee Chairman Robert Morris' estate in Manheim, Pennsylvania. Morris, whose financial wizardry (and personal fortune) was a driving force of the war effort, was a partner in the most successful prewar mercantile firm in Philadelphia. His best captain had been John Barry.

As luck would have it, Barry not only met Washington but also Morris, who was coincidentally at Valley Forge. As his former captain began a harangue against Hopkinson, Morris cut him short. He may have to judge this affair, the chairman said, and would need to hear both sides.5 Later, after Barry shared the details of his plan, Morris and Washington were supportive. Returning to his estate, Morris found the charges from Hopkinson awaiting him. The captain, meanwhile, proceeded to Reading and his home.

Charges and Plans

In the New Year, Barry was summoned to appear before Congress to answer Hopkinson's charges.6 He arrived in York ready to fight, but Marine Committee Secretary John Brown, yet another friend of Barry's, kept him calm and helped write the captain's version of the Effingham affair. It was a thorough rebuttal of Hopkinson's charges, concluding with Barry declaring himself "unworthy of the Commission the Honorable Congress had been plased [sic] to give me could I tamely put up with a different treatment."7

Brown moreover arranged a meeting with the Marine Committee during which Barry outlined his plan. He intended to take the barges and boats at Bordentown, slip past the British in Philadelphia, and harass their supply ships coming up the Delaware River, which was then more covered with winter's ice than enemy warships. The committee approved the plan, but Congress first had to decide the Barry-Hopkinson affair. Barry's staunch allies, Morris and Brown, could hold the day with their political infighting skills.

Hopkinson's congressional cronies, meanwhile, learned of Barry's scheme. Throughout the rancorous debate that followed, they insisted that the captain "be not employed in the expedition" because of his insubordination.8 The motion to discipline Barry was made and seconded. The roll call was read and the votes tallied. It was a tie.

Instead of a reprimand and expulsion, the Marine Committee ordered Barry to "proceed immediately" on his mission, and ordered Hopkinson to "provide Captain Barry with [all] war-like provisions and other measures as he may [require]."9

The captain stopped at Valley Forge en route to Bordentown. Winter was taking its toll on Washington's Soldiers; their threadbare, starving countenance was quite a contrast to the creature comforts the members of Congress enjoyed in exile. During a discussion on the state of the war, the commanding general noted David Bushnell's eccentric scheme to float barrels of explosives down the Delaware, in the hope they would detonate against British ships.10 Washington offered Barry what assistance he could, giving him authorization to detach troops from Brigadier General James Mitchell Varnum's command at Burlington, New Jersey, for his enterprise.

A Flotilla and a Foray

Barry arrived at Bordentown intending to recruit crews for four barges. Despite the availability of more than enough idle Sailors, he could get only two dozen; his open-boat mission in the dead of winter against the best navy in the world was not very enticing. Fortunately, he was able to persuade Luke Matthewman, his first officer from the Lexington, to serve as second in command. Fifteen Soldiers were detached from General Varnum's brigade, and even Hopkinson was cooperative. An expedition under Captain Joseph Wade with the same goal soon departed, taking their vessels overland to below Philadelphia. Barry would take the more direct route down the Delaware.

Around 10 February, Barry took two barges, each armed with a 4-pounder in its bow, and proceeded to slip past Philadelphia on a cold winter night. The barges were overcrowded, the freezing Sailors huddled against the howling wind, rowing their muffled oars in unison as the boats hugged the Jersey shore. They could see the lighted brick houses of the city through the shadows of the docked British ships.

At one point a sentry yelled out an alarm. A shot was fired in the direction of the boats. The crews rowed faster, slipping farther into the darkness.11 Of his successful passage, Barry succinctly wrote: "I passed by Philadelphia with two boats."12 He made his way to the Christina River near Wilmington, Delaware. Within a week Wade arrived, enlarging Barry's command to seven barges.

Back at Valley Forge, Washington sent 300 men under his trusted subordinate Brigadier General "Mad" Anthony Wayne to raid the farms along the Jersey shore, seize what cattle they could find, and burn what forage they could not carry.13 Seeking aid in this venture, Wayne learned of Barry's squadron and issued orders on 18 February for assistance.14 Barry's boats ferried Wayne's men to New Jersey the next day. By the time Tory informants learned of Wayne's presence, the crossing was completed. The Soldiers marched to Salem, while Barry hid his barges up Salem Creek.

For four days the "rustlers" took what cattle and forage they could find, despite the attempts of Jersey farmers—patriot, neutral, and loyalist—to hide their livestock in swamps and backwoods. Wayne knew full well that time was not on his side, and the British soon sent a strong force north of Philadelphia to cross the Delaware at Bristol and intercept his cattle drive at Burlington.

Deceiving the Enemy

At first, Wayne and Barry attempted to take the herd across the river by boat but quickly discovered that cattle did not make good shipmates.15 Another idea proved more feasible. Wayne sent his wagons and four-legged food supply up the road to Mount Holly, keeping his brigade between the herd and the river. Barry was used as a decoy. He took his barges upriver to Mantua Creek and then started back down, burning every haystack along the way. The towers of smoke misled the enemy into thinking Wayne was unaware of their maneuver and therefore ripe for attack. The general's orders for Barry to burn the hay included "recompense and future Pay" for the farmers whose smoking fodder completed the ruse.16 Instead of crossing the Delaware at Bristol, the British detoured farther south to catch the marauding rebels.

For two days Barry continued southward, leaving pillars of fire in his wake. When he saw open boats filled with Redcoats on the river near Finn's Point, New Jersey, he gave word to row for Reedy Island and the Delaware side of the river. His men, spent and soot-stained, made it to Port Penn by midnight.17 Barry sent the first in a series of dispatches to Washington the following morning, 26 February: "According to the Orders of General Wayne I have Destroyed the Forage from Mantua Creek to this Place the Quantity Destroyed is about four Hundred Tons. I Shall have Proceeded Further had not a Number of the Enemies Boats appeared in Sight."18

The captain's diversion enabled Wayne to get the cattle across the Delaware and reach headquarters without incident. Barry's actions, while helping to provide for the Soldiers at Valley Forge, guaranteed that British foraging parties would only reap ashes in New Jersey.

First Contact

A snap of Arctic weather then refroze the Delaware for a week. On 7 March, word reached Barry at Port Penn Tavern, Delaware, that three sails were sighted off Bombay Hook, heading north. The shrill whistle from boatswains' pipes pierced the quiet town, and Barry's crews met him at their boats. He informed them that two transports and a schooner would soon sail by. With their rowed barges hidden along the shore, the Continentals would have the element of surprise.

As soon as the transports approached their position, Barry gave the order to attack. Three barges under Luke Matthewman rowed after the closest prey, while Barry took the other four after her partner in midstream. Matthewman's quarry, the Mermaid, surrendered without a shot fired. Barry's target, the Kitty, fired her six 4-pounders, but her green gun crews hit nothing but water. Barry's gunner, however, was quite accurate with his 4-pounder. The boats reached the Kitty just as her colors were struck. Both transports were found to be laden with forage for British dragoons' mounts.

The British schooner Alert approached making no effort to change course despite what was occurring in front of her. Barry sent the Kitty's crew below, battening the hatch over them. He next directed Matthewman to take his boats to starboard. With his four barges to port, Barry and some of his men sent the Kitty straight at the schooner.

Before any fighting broke out, however, Matthewman's barge, flying a flag of truce, reached the schooner. He proposed honorable terms for surrender, and surprisingly, given the Alert mounted 20 guns and had superior manpower, her captain, Daniel Moore, accepted the offer. Three women were on board the schooner, wives of British officers in Philadelphia. Hastily drawn articles were signed granting "every Lady in the Ship to have their Baggage . . . [and] to be Sent to Philadelphia By the first Ferryman . . . the Men to Remain Prisoners of War to be Exchanged."19 The prisoners included one major, two captains, three lieutenants, and 130 soldiers, sailors, and marines. The Alert turned out to be a great present for Washington. She carried a huge supply of engineering tools and correspondence belonging to Colonel John Montresor, the British Army's chief engineer in America.

But there was no time to enjoy success. The tide was ebbing, the sun was sinking, and British warships were sighted. Barry ordered his prizes and barges back to Port Penn.

While the shallow waters around Reedy Island would keep the ships away, Barry knew they made no difference against the enemy's long guns and would pose no problem to landing boats carrying troops in greater number than his own force. Still, he made plans to defend his prizes, meeting with Delaware Congressman Nicholas Van Dyke, who arrived with some local militia.20 The three prizes were unloaded and the transports' 4-pounders were removed, but Barry ordered the hay left on board.

Barry then fired off two dispatches. One requested reinforcements from Brigadier General William Smallwood in Wilmington. The other went to the Marine Committee, relating both his victory and desire that the Alert be kept as a Continental vessel.21 The schooner, smaller and faster than had been his sunken frigate, would make an excellent raider against British ships. Congress would approve the request three days later, suggesting Barry "take command of her yourself or bestow it on some brave, Active, prudent officer."22 Next, Barry paroled Moore and a British lieutenant to escort the British wives to Philadelphia.

Running Fight on the Delaware

Dawn on 9 March found four British ships off Reedy Island: the Experiment (50 guns) under Captain James Wallace, the Brune (20), and two sloops, the Hotham and New York. Barry was ready. He would not pit his men in an all-out defense against superior guns and manpower (Smallwood did not send a single Soldier). And, if he could not keep his prizes, he would ensure they would not be retaken.

He also had another enemy to contend with: the weather. Overnight, a nor'easter came up the Delaware, with raw winds blowing snow and sleet. The thinly clad Sailors could do little more in the bitter cold than shiver and wait.23

In James Wallace, Barry faced an experienced fighter. The British captain bided his time, letting the tide dictate his movements. As it rose, he moved his squadron in as close as their drafts would allow. At about 1400, Barry was writing a letter to Washington:

Tis with the Greatest Satisfaction Imaginable I inform You of Capturing two Ships and a Schooner of the Enemy . . . the Schooner is a Most Excellent Vessel for Our Purpose . . . [there] are a Number of Engineering Tools on Board. . . . By the Bearer Mr. John Chilton have sent You a Cheese and a Jar of Pickled Oysters which Crave Your Acceptance.24

As he wrote, Wallace's ships opened fire on Port Penn. Unruffled, Barry finished the letter while giving orders to burn the two transports. Then he boarded the Alert and began sailing her behind Reedy Island. Displaying a good commander's ability to think like one's opponent, Wallace had the Experiment approach the northern end of Reedy Island. As the Alert passed the northwestern point, the British ship opened fire. The Alert's 4-pounders were no match for the Experiment's guns, and with the burning Kitty and Mermaid beyond saving, Wallace's consorts joined the pursuit, coming up past Port Penn.

The schooner proved hard to hit, but some of her crew found the roar of cannon stronger than their courage. They made for her small boat, only to encounter Barry, whose gruff orders and imposing presence sent them back to their stations. Within minutes, the Experiment's bow-chasers were splintering the Alert's stern and tearing into her sails and rigging.

Once alongside a sandbar above Reedy Island, Barry roared, "Hard a port!" and deliberately ran the Alert aground. Although forced to abandon his ship to the British, Barry and his crew levered each of her guns off its mount and overboard. He then coolly ordered the small boat manned and rowed ashore. He and his men made their way back to Port Penn, and during the night took their barges up the Christina River.25

As a result of Barry's adventures, the British were forced to increase their presence on the Delaware, blockading the Christina and vigilantly patrolling both sides of the river. Save for one more "hay ride" to New Castle, Barry spent the next four weeks in Wilmington.26 Varnum's Soldiers were ordered back to Valley Forge.

Finally, Barry returned to White Hill in May to find that most naval personnel, including Thomas Read, had left for Baltimore. He found Mrs. Read still at her residence and accepted her offer to take the guest room for the night.

The story was passed down through the Read family that Barry was midway through his morning shave when Mrs. Read breathlessly informed him that British soldiers were sighted. He finished his shave, packed his saddlebags, and left out the back door as enemy troops came to the front. The resourceful Mrs. Read then invited the commanding officer to breakfast.27

The British stayed in White Hill long enough to burn more than 40 ships, including what remained of the Effingham. But they would not catch John Barry that day. He was on his way to Reading and Mrs. Barry, ending his Delaware River escapades as they had begun—on horseback.

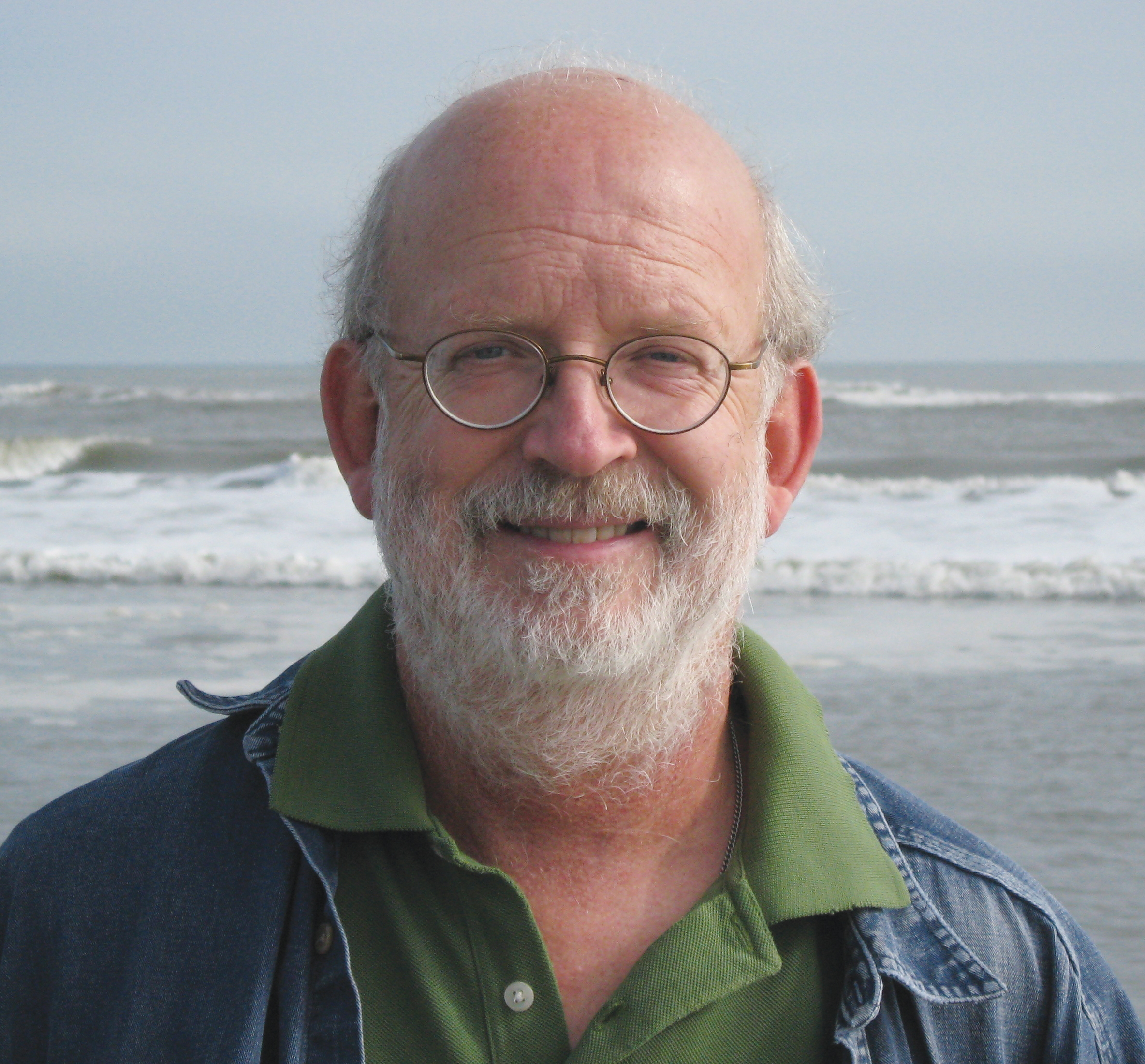

Reality Better than FictionJohn Barry's life reads like a Patrick O'Brian novel. Born in 1745, Barry was sent to sea as a child to escape the Irish penal laws and arrived in Philadelphia around 1760. By the age of 21 he was skipper of a small schooner, and eight years later he was captain of the Black Prince, said to be the finest merchantman in the colonies. Barry later supervised her rerigging when, as the Alfred, she became one of the first warships in the Continental Navy. In 1776 he commanded the brigantine Lexington when she captured the Edward and several armed merchantmen. For his barge adventures on the Delaware River, Congress rewarded Barry with command of the frigate Raleigh, which he lost off the coast of Maine in a nine-hour running battle with two enemy ships under the command of his old nemesis, Captain James Wallace. After commanding the privateer Delaware, Barry next found himself on the quarterdeck of the frigate Alliance. From there he faced mutiny, icebergs, a desperate (and victorious) battle against two British warships, intrigue with Benjamin Franklin, and one last old time sea battle—fought weeks after the Treaty of Paris ended hostilities. Rendered penniless after the war, Barry attended the Pennsylvania Assembly's sessions regarding ratification of the Constitution and was ringleader of a gang that shanghaied two anti-Federalist legislators, guaranteeing a quorum for passage. He returned to sea from 1787-89 as merchant captain. A voyage to Canton with the Asia helped restore his fortune. Recalled to service by President Washington in 1794, he was named first captain in the U.S. Navy and oversaw the construction of the new service's frigates, including his own 44-gun USS United States. Twice married but childless, he served as a mentor to the next generation of naval heroes. He died in 1803, after a long battle with asthma. Tim McGrath |

1. Legend has it that, on Washington's orders, Barry led a wagon train of baggage belonging to Hessian prisoners back to Philadelphia. However, in the Fitzpatrick edition of Washington's Papers at the Library of Congress, "Capt. Barry" is footnoted as "Captain Thomas Berry (?), 8th Va. Regiment." The 8th was comprised of German speaking Virginians, so it's more than likely not John Barry.

2. George Washington Papers (GWP), Washington to Middle Department Naval Board, 27 October 1777, Library of Congress (hereinafter cited as LOC).

3. LOC, Journals of the Continental Congress (hereinafter cited as JCC), John Barry to Marine Committee, 10 January 1778.

4. LOC, Hopkinson and Wharton to Robert Morris, 14 December 1777.

5. LOC, JCC, Robert Morris to Marine Committee, 19 December 1777.

6. LOC, JCC, Congress to John Barry, 30 December 1777.

7. Independence Seaport Museum (hereinafter cited as ISM), Barry-Hayes Collection, John Barry to Congress, 10 January 1778.

8. LOC, JCC, 29 January 1778.

9. LOC, JCC, Marine Committee to Barry, 29 January 1778.

10. Naval Documents of the American Revolution (hereinafter cited as NDAR), Vol. 11, pps. 172-74.

11. Martin J. Griffin, The History of Commodore John Barry (Philadelphia, Catholic Historical Society, 1897), p. 28.

12. ISM, Barry-Hayes papers, Memorial to Congress, 1785.

13. Willard Sterne Randall, George Washington—A Life (Henry Holt, New York, 1997), p. 351.

14. LOC, GWP, Anthony Wayne to John Barry, 18 February 1778.

15. Ibid., Wayne to Washington, 25 February 1778.

16. Ibid., Wayne to Barry, 23 February 1778.

17. LOC, GWP, Barry to Washington, 26 February 1778.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid., Daniel Moore, Luke Matthewman, and John Barry, Capitulation Articles, 7 March 1778.

20. Ibid., General Smallwood to Washington, 9 March 1778.

21. LOC, JCC, Barry to Marine Committee, 8 March 1778.

22. Ibid., Marine Committee to John Barry, 11 March 1778.

23. Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Christopher Marshall Diaries, 9 March 1778.

24. LOC, GWP, John Barry to George Washington, 9 March 1778.

25. NDAR, Vol. 11, pp. 559-60.

26. Barry attended a sale of prizes, only to find that the engineering tools he had wanted to ship to Valley Forge had been pilfered by the very militia in charge of them.

27. William Bell Clark, Gallant John Barry (New York, MacMillan, 1938), p. 155.