Tensions between Spain and the United States arose long before the Spanish-American War broke out on 21 April 1898. In both the 1868–1878 and the April 1895 Cuban uprisings against the Spanish, the United States aligned with the Cuban revolutionaries, even going so far as to provide aid to them in the struggle. Indeed, the Spanish-American War almost started in 1873 when 53 men, including several U.S. citizens, were executed by the Spanish on board the American ship Virginius for doing just that.

In April 1895, an uprising led by Cuban revolutionaries spurred the Spanish government to dispatch General Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, often referred to as “The Butcher,” to calm the disruption. His policies, which dictated the relocating of Cubans into “reconcentration camps,” led to the starvation and death of some 100,000 Cubans. In the United States, news of General Weyler’s tactics, paired with unsubstantiated stories from the sensationalist “Yellow Press,” led to outrage and pressure from the American public to put a stop to the violence between the warring parties. Though partial independence was promised to Cubans in 1897, all parties remained on high alert.

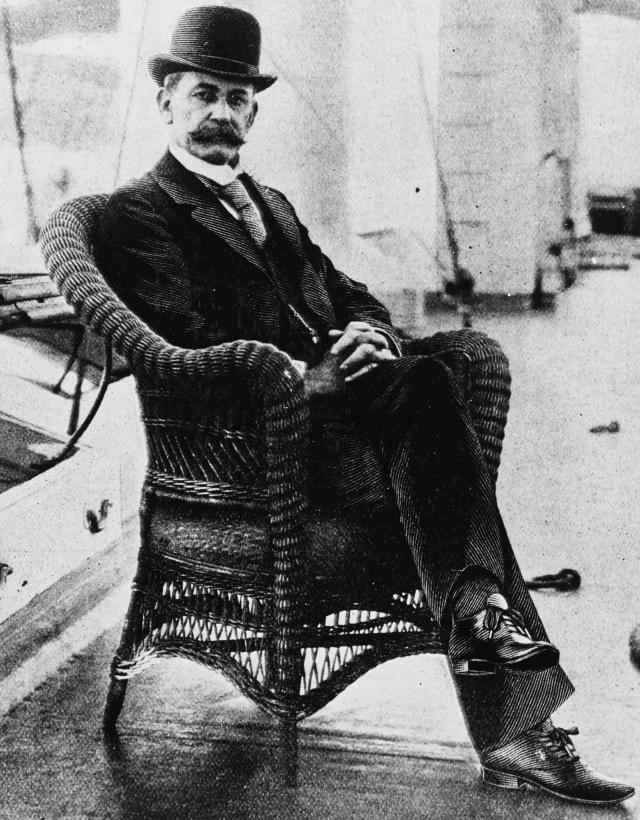

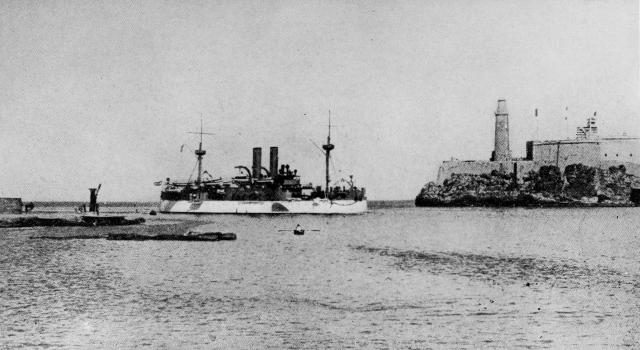

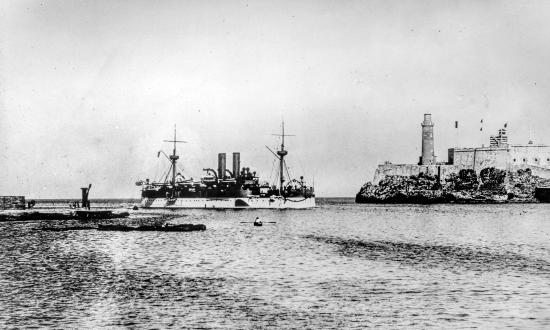

Pro-Weyler forces launched a series of riots in Havana, Cuba, in January 1898, and concern for U.S. citizens in the area reached new heights. On 24 January, President William McKinley made the decision to dispatch the second-class battleship USS Maine to the area to provide some level of protection and assurance to those residing in the area. The Maine arrived at port at Havana the following day under the command of Captain Charles Sigsbee.

All too aware of the delicate situation on land, Sigsbee ordered his enlisted men to remain on board the ship at all times so as to avoid the possibility of any conflict. Apprentice First Class Ambrose Ham, a crew member on board the Maine, noted that “time was beginning to drag” as the days blended into two weeks on board the vessel. Unfortunately for the officers and crew of the Maine, their boredom would be interrupted by tragedy.

The night of 15 February 1898 began like any other for the men of the Maine, which remained dutifully moored in Havana’s harbor. Crewmen were spread about the ship performing their nightly duties, while others prepared to turn in for the night. Some of the ship’s officers enjoyed time in the mess, their state rooms, or in the officers’ smoking quarters. Captain Sigsbee was in his quarters, reading and writing letters to loved ones and officers back home.

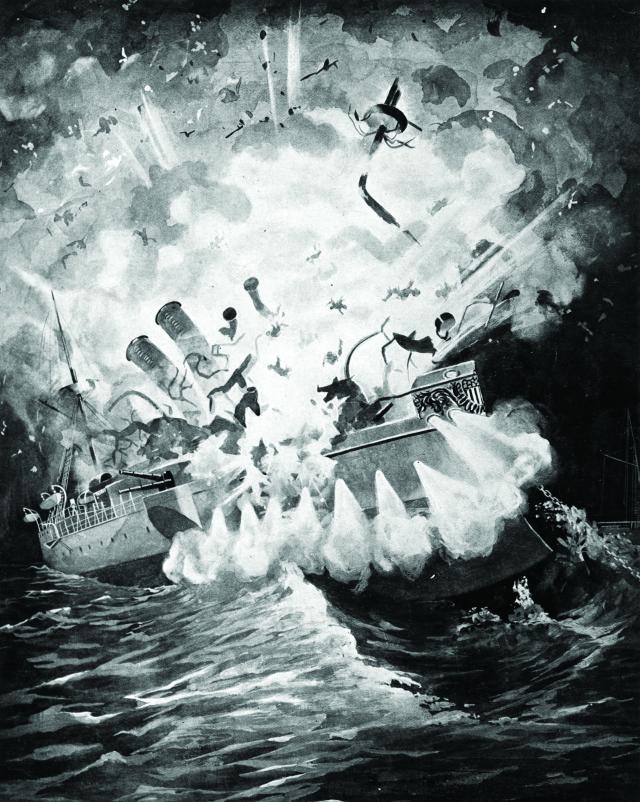

In his recollection of that night’s events, Sigsbee recalled hearing “a bursting, rending, and crashing sound or roar of immense volume . . . followed by a succession of heavy, ominous, metallic sounds” at around 2140. Seconds later, he felt the vessel lurch as the lights cut out and his cabin filled with a thick, choking smoke.

Elsewhere on board the ship, Apprentice First Class Ambrose Ham saw a column of flames shoot into the sky, “engulfing the forward part of the ship,” just before being knocked unconscious by a piece of debris turned projectile.

Sigsbee, with the aid of one Private William Anthony, made his way to the main deck where he was able to assess the situation before he realized the Maine was sinking rapidly into the harbor. Sigsbee rushed to the poop deck, where he met more officers stunned by what Sigsbee then knew to be an explosion. Smaller fires erupted through the ship, and Sigsbee directed his men to control the blaze. As his eyes adjusted to the darkness of night, Sigsbee realized that injured, dead, and dying men floated in the water surrounding the ship, which appeared to be breaking apart before his eyes.

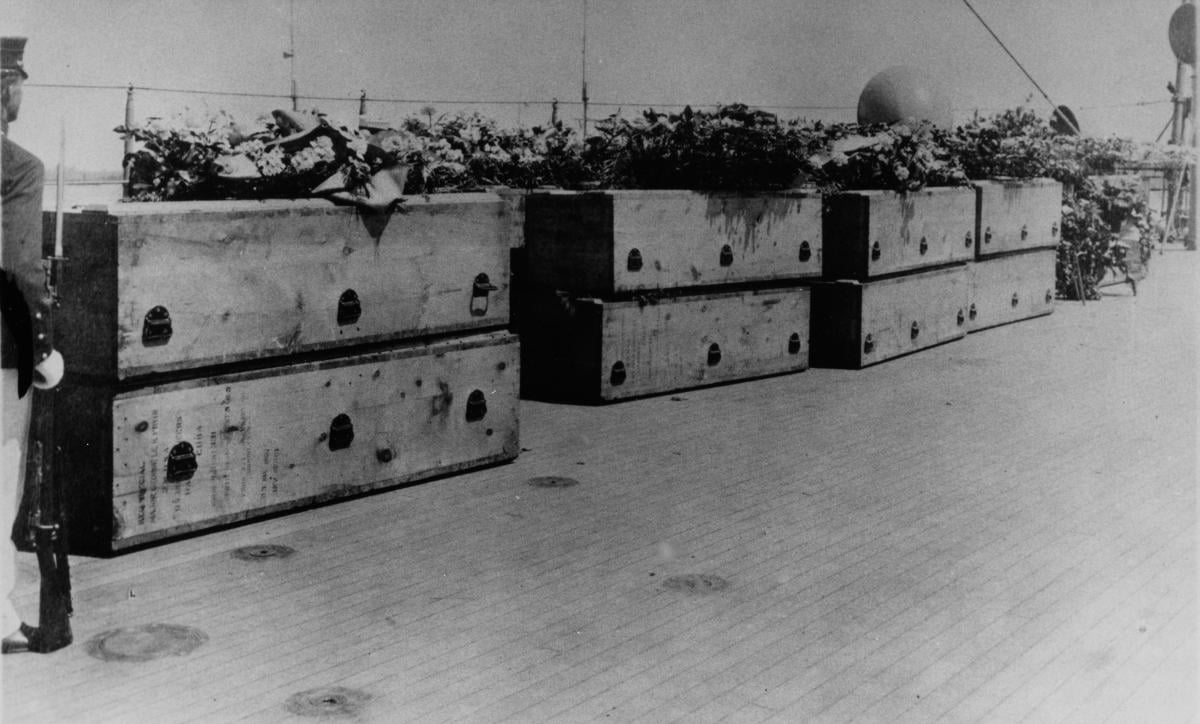

Nearby ships, such as the civilian steamer City of Washington and local Spanish officials jumped into action almost immediately. They hauled survivors from the debris-strewn waters and provided emergency medical care to those in peril. As rescue options were under way, pops rang out as magazines on board the ship ignited. Sigsbee waited for his men to leave the damned vessel on what few lifeboats were not destroyed in the blast. He was the last to escape. They later would come to discover that 260 men perished in the explosion and ensuing chaos that took place aboard the Maine.

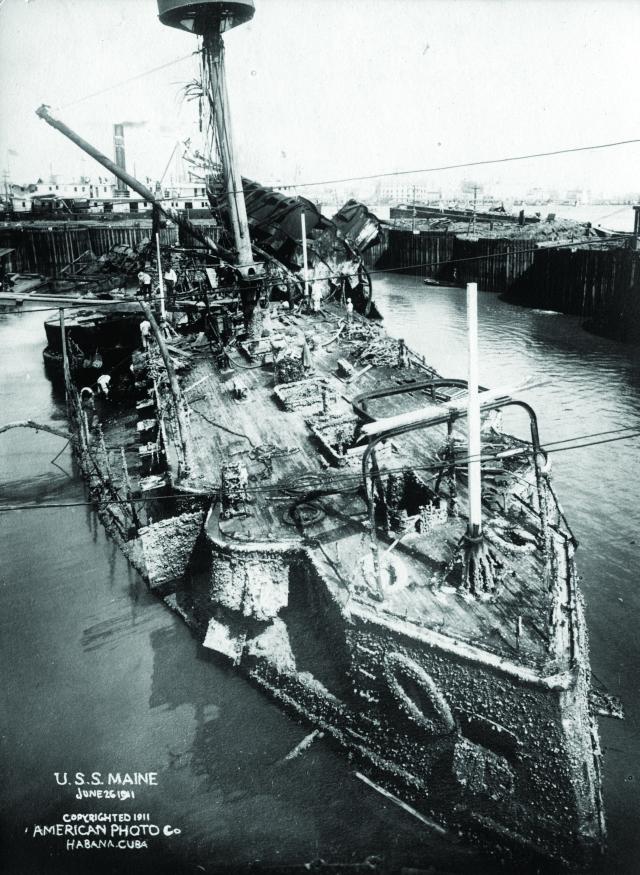

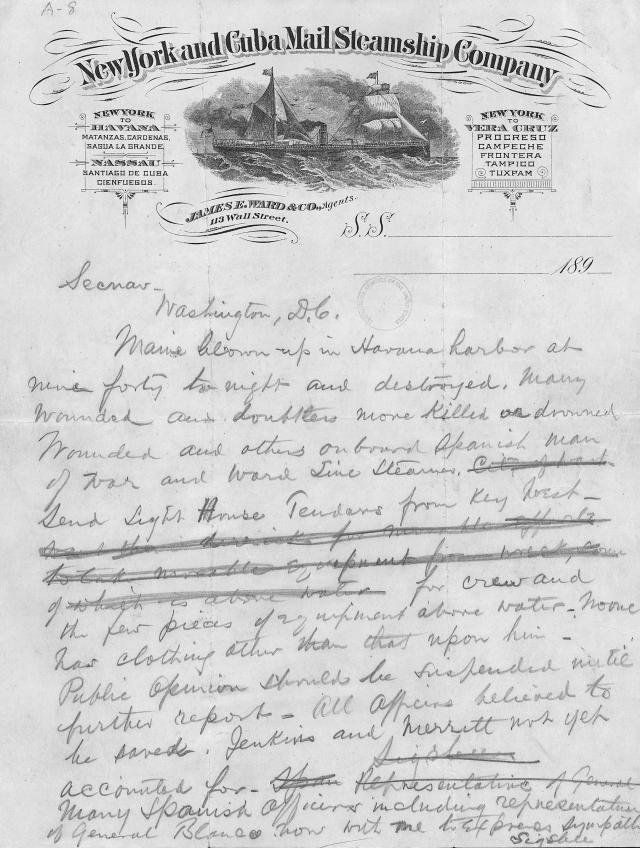

Reaching the safety of a rescuing vessel, Sigsbee quickly realized the delicate nature of his position. As tensions between Spain and the United States already were near their boiling point, Sigsbee took great care in authoring his initial report of the incident. Upon receiving news of the disaster at Havana, the U.S. Navy promptly formed a board of inquiry to investigate the cause behind 15 February’s momentous loss. In examining the state of the submerged wreck of the Maine, the Navy determined a mine likely detonated under the ship, though they did not assign any blame as to the source of the mine.

As was the case some years before, the “Yellow Press” took hold once again and published stories blaming Spain for the placement of the mine. The American public grew even more outraged toward the Spanish, and the pressure mounted for the United States to take action against what many perceived as an act of war. President McKinley requested permission from Congress to intervene in the conflict on 11 April 1898, and the blockade of Cuba and Spain was initiated 10 days later. Spain declared war on 23 April, and Congress issued an official declaration of war on 25 April.

The findings of the U.S. Navy’s inquiry into the sinking of the Maine were not unanimously accepted. Some officers believed the ship’s magazines were ignited by a fire in the ship’s coal bunker, causing a large explosion and fire to consume the ship. While a 1911 board agreed with the initial findings, a 1976 book by Admiral Hyman G. Rickover provided evidence to support the coal-fire theory. To this day, the exact cause of the loss of the Maine is a subject of great debate. While the tragedy did not immediately spur the Spanish-American war, it is commonly seen as a point of no return in the buildup to the historic conflict

1. The Sinking of Maine, Naval History and Heritage Command.

2. C.D. Sigsbee, The "Maine"; an account of her destruction in Havana harbor, the personal narrative of Captain Charles D. Sigsbee, U.S.N. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1899.