During World War II, the U.S. Coast Guard played a key role in the Battle of the Atlantic. In concert with the U.S. Navy and Allied forces including the British, Canadian, Free French, and Polish navies, Coast Guard cutters escorted thousands of merchant ships carrying war matériel crucial for victory in Europe. One of the Coast Guard’s most dramatic engagements during the long Atlantic struggle was the duel between the USCGC Spencer (WPG-36) and German submarine U-175 on 17 April 1943.

The Opponents

Service in a German U-boat was arduous. Conditions were extremely cramped; the sub was essentially a long tube containing torpedoes, engines, motors, bunks, radios, a control room, and a very small galley divided by watertight doors. No one showered for entire patrols. There was no refrigeration and food quickly spoiled; crewmen gave moldy loafs of bread nicknames like Kaninchen because they looked furry, like rabbits. Submarines in World War II spent significant amounts of time on the surface, leaving the crews exposed to bad weather and air attack; the standard time for a U-boat emergency dive was 35 seconds. Even leaving aside the threat of enemy action, operating an undersea vessel was inherently hazardous, especially as crew and equipment quality diminished throughout the war.

U-175 was a Type IXC U-boat, with a length of 251 feet and about 50 crewmen. She was powered by a combination of diesel engines and electric batteries and armed with torpedoes, two deck guns, and smaller antiaircraft guns. U-175 was commissioned in December 1941 under the command of Kapitänleutnant Heinrich Bruns, a career officer who had previously enjoyed sailing on board the Horst Wessel (now the training vessel USCGC Eagle [WIX-327]) and been seriously wounded while serving in torpedo boats. (Those ranked Kapitänleutnant—literally, “Captain-Lieutenant”—traditionally were addressed in the World War II era as Herr Kaleun. The U.S. naval equivalent rank would be lieutenant.) Bruns’ crew regarded him as ambitious but fair; he normally operated with a requisite level of caution but on the hunt could be more daring than many of them would have preferred. In port he would deal with the extreme stress of commanding a wartime U-boat by getting very drunk with his engineer officer, Oberleutnant Leopold Nowroth.

U-175’s first two patrols were to the Caribbean and off the coast of West Africa, during which she sank nine ships and sustained heavy damage from an air attack. After limping back to France, U-175 received hasty repairs, a fresh topside coat of light gray paint, and some new personnel before sailing on her third patrol.

This time, she was headed for the North Atlantic.

The Spencer was a 327-foot Treasury-class cutter, commissioned in 1937. Relatively fast, heavily armed, with long range, and exceptionally well riding, Treasury-class cutters including the Spencer, Duane (WPG-33), Ingham (WPG-35), and Campbell (WPG-32) proved superlative convoy escorts and shouldered a disproportionate amount of the fight early in the Battle of the Atlantic. Another Treasury-class cutter, the Alexander Hamilton (WPG-34), became the Coast Guard’s first ship loss of World War II, when U-321 torpedoed the cutter off Iceland in late January 1942.

By early 1943, the Spencer’s commanding officer, Commander Harold Berdine, and his men were seasoned combatants. The once-white hull was painted in a maritime camouflage scheme. The crew had nearly doubled to more than 200 officers and enlisted; personnel were crammed into berthing areas filled with folding chain bunks stacked several high. The ship bristled with additional armament, including machine guns, automatic cannon, “mouse trap” antisubmarine rocket launchers, and depth charges. The Spencer also had been refitted with radar, hydrophones (later known as passive sonar), active sonar, and radio direction-finding equipment, all of which made U-boat detection somewhat less difficult.

Convoy duty was characterized by endless days and nights of stressful tedium watching for periscopes or surfaced subs, often in terrible weather and rough seas. The merchant ships in convoy often would zigzag in formation as their escorts maintained station or darted around them like protective dogs around sheep. Lookouts clad in layers of oilskin clothing, peacoats, and watch caps strained their eyes at sea and sky; any significant wind made the feathery wake from a periscope almost indistinguishable from a whitecap. The boredom would be interrupted by excitement when the enemy was sighted, or horrified surprise when a torpedo was detected or, worse, a nearby ship exploded from one that had slipped through unseen.

Escorts normally steamed at a modified readiness condition. When General Quarters was sounded, everyone, from the yeomen to the segregated stewards, would run to their assigned battle stations and don helmets and lifejackets.

Convoy escorts picked up crewmen who had managed to escape their sinking ships when operationally feasible; the survival time for victims floating in the winter North Atlantic was short.

Sonar Pings a Stalker

Convoy HX233 departed Halifax, Nova Scotia, on 6 April 1943. It consisted of 58 merchant ships and a varying number of escorts under Task Unit 24.1.3, including the Spencer and sister ship Duane, plus two British and two Canadian warships. Some of the merchant ships also carried U.S. Navy armed guards, who could provide limited defense with deck guns. The convoy’s ultimate destination was Liverpool, England. Task Unit 24.1.3 was under the overall command of U.S. Navy Captain Paul Heineman, who was embarked in the Spencer. Commander Berdine and Captain Heineman made an effective team, although the Navy officer didn’t much care for the more egalitarian atmosphere on board the Coast Guard cutter.

HX233 was detected by a U-boat a few days after sailing, and by 16 April, seven U-boats—including U-175—were converging on the convoy.

Action began on 16 April, when the Spencer dropped depth charges and launched mousetrap rockets at a suspected submerged submarine, with no results. The convoy was still about 600 miles southwest of Ireland, crossing the perilous North Atlantic air coverage gap, an area outside the range at which Allied aircraft could effectively conduct antisubmarine operations. The escorts knew the U-boats would be more daring without Allied air cover.

The weather was fair and seas were calm on 17 April, but the day began with a shock as U-628 torpedoed the British merchant ship Fort Rampart. Commander Berdine piloted the Spencer to screen the Canadian corvette HMCS Arvida as she picked up survivors. The Spencer then maneuvered to rejoin the convoy. As she closed, the sonar operators picked up another contact at a range of about 1,500 yards. Berdine hurried back to the bridge and ordered full speed ahead to investigate.

Less than a mile away and about 50 feet below, U-175 was stalking the tanker G. Harrison Smith. The submarine was at periscope depth, and Kapitänleutnant Bruns was assessing the target through the scope. He was eager to attack, blessing his luck that the convoy had come right to him, while his executive officer and crew were somewhat anxious about his decision to engage in broad daylight. Then his hydrophone operators heard a rapidly approaching warship, followed shortly by the unmistakable sound of active sonar pinging off their hull. Suddenly faced with an incoming Treasury-class cutter filling his periscope, Bruns briefly considered firing torpedoes but instead ordered immediate evasive action; U-175 dove deeper while turning to starboard.

Berdine in the Spencer and Bruns in U-175 were trying to anticipate each other’s actions. Bruns wanted to break contact or possibly torpedo the Spencer; Berdine’s objective was to drive off or sink U-175.

Berdine figured the sub would come right to evade. He immediately ordered a spread of 11 depth charges as the Spencer steamed over the U-boat’s estimated position. The round canisters dropped and sank to a preset depth before exploding.

Below, the crew of U-175 heard the cutter pass overhead, and then the depth charges began detonating beneath them. Energy travels much more efficiently in water than in air; the force generated by hundreds of pounds of high explosives violently rocked the submarine and her crew. The damage was substantial and included forward flooding, disabled bilge pumps, dislocated engines, and broken gauges. The hull was warped so severely that the watertight doors could not be closed.

Most critically, U-175’s buoyancy had been disrupted, and she began an uncontrolled plunge toward the ocean floor miles below. U-175 previously had survived an unintended dive to more than 1,017 feet, and the crew knew they had until roughly that deep to restore buoyancy—any deeper and the water pressure would crush them like an empty can. Working frantically, they managed to stop the descent at about 985 feet. Catastrophe momentarily averted, the U-boat began drifting upward as the rattled crew attempted to repair the damages.

Depth Charge Bull’s-Eye

Meanwhile, the Spencer was still tracking her quarry. A column of the convoy’s merchant ships was getting uncomfortably near; they were within easy torpedo range if the U-boat was still operational. Berdine ordered another spread of 11 depth charges—this time set to explode deeper—and then a volley of mousetrap rockets. The deadly canisters again dropped from the Spencer and blew spectacular explosions of water in the wake.

The cutter’s second depth charge barrage was dead-on. U-175 was rocked again by underwater blasts, this time rupturing the pressure hull, damaging electric motors, breaking open battery containers, and activating two torpedoes in their tubes. The U-boat was flooding now, filling with toxic gas from the batteries, and two of her torpedoes were possibly about to explode. To remain submerged was certain death; the engineer officer, Oberleutnant Nowroth, ordered ballast tanks blown for an emergency ascent. Bruns ordered the two torpedoes jettisoned and concurred with preparations to abandon ship.

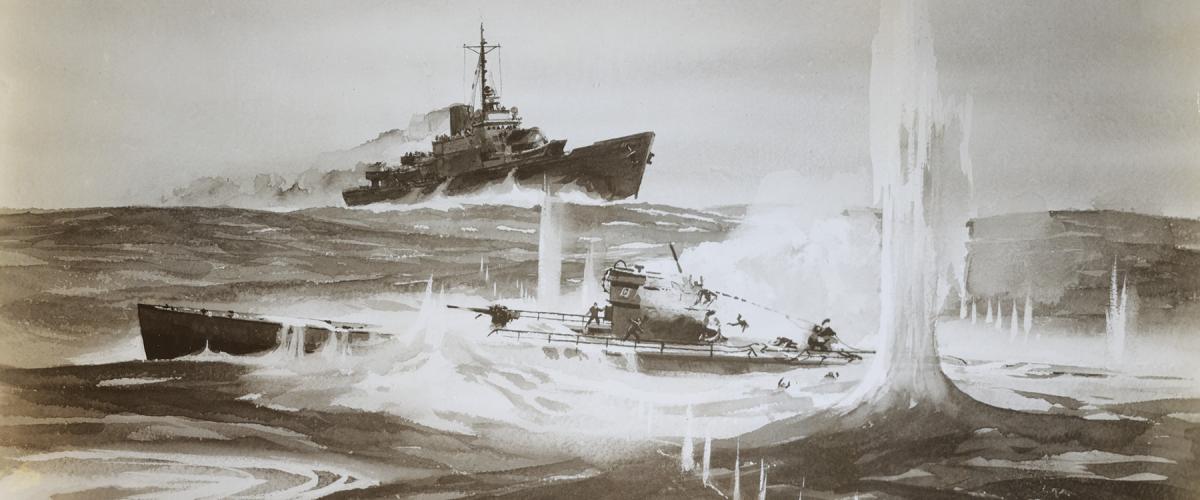

U-175 suddenly surfaced about 2,500 yards from the Spencer. When a U-boat popped up in close proximity, it was critical to stop her crew from manning the deck guns to engage the escorts. The Spencer immediately opened fire with any weapons that would bear, joined shortly by the Duane and naval guards on nearby merchant ships. They scored several hits, mostly on the U-boat’s prominent conning tower. But some of the rounds fired from the merchant ships hit the Spencer, causing multiple casualties. Berdine ordered flank speed and prepared to ram as his gun crews kept pouring fire at the U-boat.

On board U-175, the crew was desperately trying to escape before the U-boat sank. Bruns was first out of the conning tower hatch, just as it received a direct hit from a high explosive shell. One of his legs was blown off, and he died instantly. The next two men out also were killed.

Others began jumping overboard and, once it became clear that they had effectively surrendered, Captain Heineman directed Berdine to stand down from his ramming attack. The gun crews ceased fire. It had been seven minutes since the U-boat broke the surface.

Boarding a Battered U-boat

By now, all surviving crew members of U-175 had abandoned ship. Engineer Officer Nowroth was the last man off; despite being wounded, he had managed to open the ballast-tank vents. Somehow, the battered submarine was still afloat on the calm Atlantic swells.

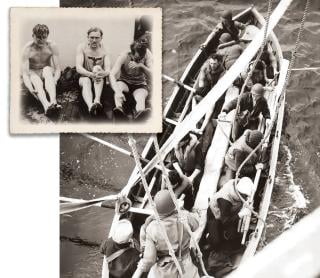

Boarding a U-boat was a golden opportunity to recover enemy classified materials and gather other intelligence. Captain Heineman directed Commander Berdine to make the attempt. Berdine immediately ordered the ship’s Number 2 boat readied for launch with the boarding team. Number 1 boat would have been preferred since it had an engine, but it had been hit almost directly by the friendly fire. This was frustrating; they would have to row Number 2 boat to the sub.

Once the Spencer was alongside U-175, Number 2 boat was launched under the command of Lieutenant Commander John Oren. The ship began picking up survivors as the boat crew pulled to reach the sub before it went down. The Duane also approached and began dropping lines and cargo nets to recover the German sailors. The water temperature was 54 degrees—cold but not immediately deadly. Some survivors were yelling for help. Others were missing life jackets or so incapacitated that crewmen had to haul them up via harness. Most seemed grateful to be rescued, although one Nazi officer spat at a Coast Guard lieutenant as he was pulled aboard the Duane.

Number 2 boat reached the wreck of U-175 and put a line over to the conning tower. Lieutenant Ross Bullard and Boatswain’s Mate First Class C. S. “Mike” Hall jumped aboard the U-boat, becoming the first U.S. military personnel to board an enemy ship at sea since the War of 1812. There were three dead men, one of whom was Bruns, on top of the mangled conning tower. Hall opened the hatch and prepared to drop down a grenade but saw only bodies floating in the flooded compartment below. Unfortunately, the main deck of the sub was already awash, and it would have been suicidal to enter the hull. The boarding team quickly cut the line and disembarked into the Number 2 boat (some accounts have them briefly ending up in the water as the sub literally sank beneath them). They began picking up survivors in conjunction with one of the boats from the Duane.

U-175 finally sank at 1227. The entire engagement had taken just under an hour and 40 minutes. The Spencer ultimately rescued 18 survivors and the Duane 22.

On board the Spencer, the German prisoners were processed. Most were hypothermic, and several were wounded. First life jackets, underwater escape apparatus, and wet clothing were removed, the latter to be later carefully searched. There were far too many prisoners to all fit in the ship’s brig, so they were given blankets and escorted to holding areas on the exterior decks. A few crew members wearing .45s were detailed to guard them as they sat wrapped up, largely numb.

The Human Face of the Enemy

Spencer crew members crowded around the prisoners, suddenly face to face with the men they had been fighting minutes before. Many of the Coast Guardsmen had been escorting convoys for months, dropping depth charges on countless fleeting contacts, watching ships explode from torpedoes, and rescuing survivors. The gun crews had relished the opportunity to finally strike directly at one of their elusive opponents, with many cheering as shells exploded on the surfaced sub.

Now, faced with the German sailors’ humanity after rescuing them from their common enemy of the sea, the Coast Guardsmen gave them coffee and cigarettes. Pharmacist’s Mate First Class William Crumbaugh provided first aid; ship’s surgeon John Davies was busy treating wounded from the friendly fire. The prisoners later were taken below to the crew’s mess for a hot meal, some still in their underwear; the German officers later lost their silverware privileges when it was discovered that some of them were retaining knives.

Out of U-175’s crew of 54, 13 were killed and 41 were rescued. The Spencer sustained 25 crewmen wounded from the friendly fire, including her chief yeoman. One member, Radioman Third Class Julius Petrella, later died of his wounds. He was buried at sea the following day with full military honors in a ceremony presided over by Commander Berdine and attended by Captain Heineman. The ships of the convoy steamed silently in the distance as he was committed to the deep.

The Spencer and Duane remained with Convoy HX.233 until 20 April, when they proceeded to Greenock, Scotland, and transferred their prisoners and seriously wounded. The German sailors were thoroughly debriefed by British naval intelligence. Mission accomplished, the officers of the Spencer had a celebratory dinner, and the crew commemorated their victory by painting a cartoon of Popeye launching a depth charge at the silhouette of a U-boat on the stack. Convoy HX.233 arrived at Liverpool on 21 April, having lost only one ship.

The Battle of the Atlantic ended in 1945 with the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany. It was the longest campaign of World War II. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill wrote of it: “The only thing that really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril. I was even more anxious about this battle than I had been about the glorious air fight called the ‘Battle of Britain.’” Losses were heavy on both sides: 3,500 Allied merchant ships and 175 Allied warships were sunk, and some 72,200 Allied naval and merchant seamen died. The Kriegsmarine lost 783 U-boats and roughly 30,000 submariners—approximately three-quarters of its entire force.

Despite the dangers and challenges, the Coast Guard played a key role in enabling the Allies to keep the sea lanes open, ensuring not just the survival of Britian and liberation of North Africa and Western Europe, but also significantly assisting the Soviet Union’s victory as well.

The Spencer continued to serve in the Coast Guard for decades, including in the Vietnam War. The ship was decommissioned in 1974 and later scrapped.

Retired Coast Guard Captain John Waters, who as a young officer was awed by the Ingham steaming at flank speed through a beleaguered North Atlantic convoy, flying a massive U.S. flag as the sun rose, eulogized the Treasury cutters:

The 327’s battled, through the “Bloody Winter” of 1942–43 in the North Atlantic—fighting off German U-boats and rescuing survivors from torpedoed convoy ships. They went on to serve as amphibious task force flagships, as search-and-rescue (SAR) ships during the Korean War, on weather patrol, and as naval gunfire support ships during Vietnam. Most recently, these ships-that-wouldn’t-die have done duty in fisheries patrol and drug interdiction. Built for only $2.5 million each, in terms of cost effectiveness we may never see the likes of these cutters again.

The Spencer and all the Coast Guard personnel who served in World War II stand as a distinguished part of the Long Blue Line.

Sources:

Tony Cooper (transcription), “Interrogation of Survivors from ‘U-175,’ a 740-Ton U-boat Sunk by U.S.C.G. ‘Spencer’ on 17th April, 1943,” U-boat Archive, uboatarchive.net/U-175A/U-175INT.htm.

“Heinrich Bruns,” U-Boat.net, uboat.net/men/commanders/144.html.

Gordon Rottmann, SNAFU (Situation Normal All F***ed Up): Sailor, Airman, and Soldier Slang of World War II (Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2013).

Michael Walling, Bloodstained Sea: The U.S. Coast Guard in the Battle of the Atlantic, 1941–1944 (Hudson, MA: Cutter Publishing, 2009), 179–86.