The International Maritime Museum in Hamburg, Germany, reflects the importance of the city in world shipping and commerce. From the 13th through 16th centuries. Hamburg was a major center of the Hanseatic League, which controlled trade in the Baltic Sea and much of northern Europe. Salt was its most important export, and its merchants also traded in furs, timber, tar, flax, honey, wheat, rye, and cloth. Merchant ships called cogs connected the city with the ports of Europe, and merchants built warehouses to handle the products that flowed in and out of their city. One of those warehouses, a nine-story brick structure on the waterfront, has been splendidly refurbished to hold the museum’s enormous collection.

Shipping and trade continue to be essential to the city’s economy. Connected to the North Sea by the Elbe River, Hamburg is the third-busiest port in Europe. Visitors who take a waterborne harbor tour are likely to see massive container ships and the cranes that load and unload them, new cars being driven onto a ship destined for Africa, and floating dry docks where ships are being repaired. All the ships in the port, along with the cogs, carracks, and freighters that preceded them, are represented in the museum.

A jaunty nautical spirit permeates the International Maritime Museum from top to bottom, so it refers to its floors as decks. Each deck has a nautical theme, and each focuses on a particular topic, such as “Navies of the World,” “Merchant and Passenger Shipping,” and “Undersea Exploration.” Labels in German and English make it easy to appreciate the exhibits and to identify objects.

Each deck is large and packed with well-displayed artifacts and exhibits. In fact, every deck contains so much material that it would make a museum in itself, and visitors may be tempted to try to see everything. Attempting to do so will result in weary legs and a feeling of desperation as you realize you cannot see it all in a half day or even a full day. A good strategy is to take the full-color guide you receive at the admission counter to the ground-floor café, have a coffee, decide which topics interest you most, and concentrate on enjoying two decks at most.

The museum encourages visitors to begin at the top (ninth) deck. After stepping off the elevator, visitors can see 50,000 miniature ships, all built to the same scale (1:1,250). This may well be the largest collection of model ships in Europe, if not the world.

At the center of this amazing display is the small ship that started the whole collection: a one-inch lead model of a coastal freighter, given to Peter Tamm when he was six years old. Inspired by a love of the sea and all things nautical, he began collecting. The International Maritime Museum is the result.

Exhibits on the ninth deck explain the process by which model makers used drawings, molds, delicate tools, and paint to create a waterline model. Several molds are on display, including an original 1930s metal mold for the British battleship HMS Warspite. (See “Operation C,” p. 20.) Waterline models had many purposes; companies produced thousands of them, first for naval officers planning the next battle and then for boys dreaming of going to sea.

The eighth deck, with its polished wooden floor and beams encased in wood, displays a splendid collection of more than 200 maritime paintings. The majority depict sailing vessels, including a fine 1672 portrayal of English ships-of-the-line by Willem van de Velde the Younger. A large oil by Montague Dawson captures the glory of the Age of Sail with the clipper ship Lightning running downwind under full sail. In the rear of the deck visitors will see a model of Columbus’s Santa Maria made of gold.

On the seventh deck the exhibits concentrate on ocean exploration and research. One highlight is a model of Captain Nemo’s (Latin for “no man”) Nautilus that owes more to Jules Verne than Walt Disney. Full-size remote operating vehicles and a rotary drill bit for cutting through the ocean floor bring these exhibits into the present time.

Sixth-deck exhibits focus on merchant and passenger shipping. A full-size re-creation of a 2001 cabin from the sailing vessel Sea Cloud II allows visitors to step up to the luxury of traveling first class. More than 50 large models of ocean liners, break-bulk freighters, container ships, and oil tankers illustrate centuries of improvements in shipping and passenger travel. Most of these models are two to three feet long; the largest is the 22-foot Cap Arcona, a passenger liner built in 1927. Keen-eyed visitors may spot the model of the freighter Cap San Diego; the real Cap San Diego, built in Hamburg in 1961, is afloat as a museum ship less than a mile from the museum.

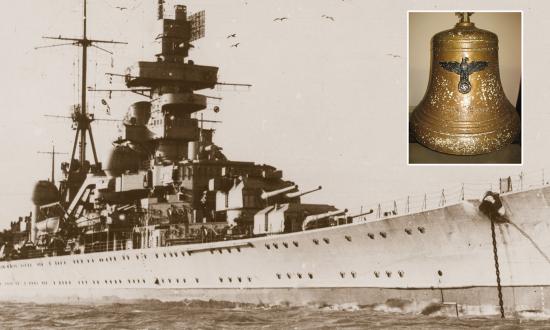

Taking the stairs or the elevator down to the fifth deck puts visitors in the War and Peace displays. Amid torpedoes old (1906) and newer (1970) and models of the Bismarck and Yamato, one might look for several notable artifacts. One of these is the leather bridgecoat worn by the captain of the World War II German submarine U-96, on whose exploits the 1981 movie Das Boot was based. Another is the long red-and-white streamer emblazoned with a skull and bones, flown by Captain Felix von Luckner over the three-masted commerce raider Seeadler during World War I. Further on is a 1919 British naval flag bearing the signatures of wartime leaders including Winston Churchill, Woodrow Wilson, and Field Marshal Douglas Haig.

The U.S. Navy is remembered on this deck with models of the 1862 ironclad USS Monitor and the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid (CV-11). (See “A New Look for an Old Icon,” p. 14.) A diorama of U.S. Fast Carrier Task Force 58, based on the well-known photograph titled “Murderers’ Row,” shows the tremendous naval resources the United States brought to World War II in the Pacific.

The lives of the sailors who manned those warships are presented on deck four with as many uniforms, hats, medals, small arms, and swords as you are likely to see outside of a supply warehouse or an armory. Two exhibits effectively recreate the living quarters of a seaman and an officer in a late 1800s warship. The sailors had hammocks and tin mess gear; the officers enjoyed staterooms with beds and dressers.

Building a wooden ship required lots of trees; Lord Nelson’s flagship HMS Victory used 6,000. Shipwrights scoured forests in search of timber growing in the correct shape to form ribs and knees. On the third floor there is an exhibit that effectively demonstrates what the shipwrights were looking for and how a bent tree became an integral part of a wooden ship.

Passing through the second deck with its myriad ship models, navigation equipment, a rum cask, and a pile of silver bars from the Dutch East India Company brings visitors back to the first deck (ground floor by American reckoning). Adjoining the extensive museum store is a full-scale replica of the lifeboat James Caird. In 1917 Ernest Shackleton and five companions made a storm-tossed voyage across the Southern Ocean to rescue his stranded crew. Sailing the replica, German explorer Arved Fuchs recreated Shackleton’s difficult voyage in 2000.

Because it is not possible in one visit to see everything the museum offers, for 10 euros you can purchase a guide to the exhibits that will show you those things you could not get to and help you plan a return visit.