Today’s nuclear-powered aircraft carriers of the Gerald R. Ford class have a length of approximately 1,100 feet—the longest of any warship ever constructed and fielded by the U.S. Navy.

The longest floating structure ever built by the Navy, however, came into existence in October 1943 and conducted flight operations the following month.

Codenamed Project Sock, the 1,810-foot long floating airfield proved the culminating achievement for the ambitious and bizarre Project Habbakuk and one of the more bizarre military engineering experiments of World War II.

Habbakuk originated in September 1942 in British Combined Operations under the command of Admiral Louis Lord Mountbatten as an ambitious plan to construct immense aircraft carriers out of an ice–wood pulp mixture called pykrete. The vessels would carry large, land-based heavy bombers to help close the Mid-Atlantic gap and protect supply convoys bound for England. Quickly and cheaply built out of nonstrategic materials, the ships would withstand mines, torpedoes, and bombs and be unsinkable. In December, Prime Minister Winston Churchill authorized research to determine feasibility of the concept.

Beginning in January 1943, the research into Habbakuk moved to Canada. At Patricia Lake in Jasper National Park, Alberta, conscientious objectors constructed a 1,000-ton, 1:50 scale model of a Habbakuk from March through April. Resembling a boathouse on the lake on account of its wooden walls and triangular roof, the model built of plain ice proved the theory of constructing an ice ship, with the model floating without issue in the summer sun.

Research determined that the cheap pykrete had limitations. To maintain compression strength, the pykrete had to be kept at temperatures at or below 5° Fahrenheit, limiting where—and when—the vessel could be constructed. By now, refined plans outlined an aircraft carrier 2,000 feet in length with a breadth of 300 feet and depth of 200 feet displacing 2,020,000 tons, placing Habbakuk’s construction requirements out of the reach of the British and Canadians and squarely into those of the Americans.

At an August 1943 conference, the British successfully brought the Americans on board with Habbakuk, to a limited degree. The Combined Chiefs of Staff agreed to establish a Combined Anglo-American-Canadian Board to continue experiments, refine design drawings, and study the construction of and facilities for a full-sized vessel. In the immediate aftermath of the conference, Churchill and Mountbatten conceived an idea for an alternative Habbakuk, one grounded in reality.

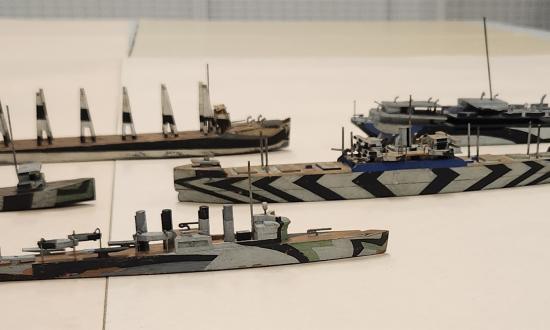

U.S. Navy Captain John N. Laycock (pictured at right) was called on to meet with a member of the British Admiralty delegation. Laycock had developed the naval landing pontoon just prior to U.S. entry into the war (see “Bridging the Gap from Ship to Shore,” August 2021, pp. 34–41), which had proven invaluable as floating causeways during the landings in the Allied invasion of Sicily. This success made the pontoons favorites with Mountbatten and Churchill.

When Laycock arrived to meet the Admiralty delegate, he found himself instead meeting Mountbatten, who congratulated the American captain on the causeways and asked about the feasibility of building a floating airfield.

At the time of the conversation, Laycock had been experimenting with folding pontoon barges on top of each other. These then could be towed to a remote destination, unfolded, and connected to form a large floating platform.

Days after meeting with Mountbatten, Professor John D. Bernal, Churchill’s scientific adviser, called on Laycock and asked about pontoons. Laycock shared his drawings and cardboard models with Bernal, who excitedly remarked, “Undoubtedly the Prime Minister will want to see this.” Laycock coolly stated he could not see Churchill without American authorization, which he received without delay.

In the evening hours of 2 September, Laycock found himself in Churchill’s guest bedroom at the White House. Propped up in bed, the Prime Minister greeted the captain enthusiastically, heaping praise on the novel landing pontoon that had been of such benefit in the Sicilian invasion. Laycock shared photographs and demonstrated his cardboard folding barge model on Churchill’s bedcovers. By flooding certain pontoons, the barge could be tilted on its side to unfold the other half, producing a surface area 175 by 200 feet. Eight such barges, when unfolded and connected, would form a floating airfield 1,500 feet by 175 feet.

Churchill saw great possibilities in the floating pontoon airfield and acted promptly. The next day, he met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and discussed the concept. On 10 September, after further weighing of its merits by an ad hoc committee convened by Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral Ernest J. King, the U.S. Navy agreed with Churchill to conduct experiments with a floating pontoon airfield. King authorized construction of the field, codenamed Sock, the following day.

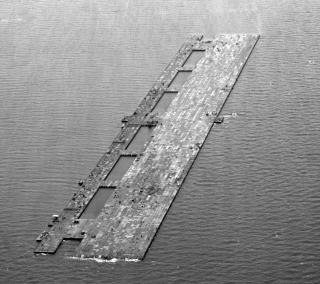

At Advance Base Proving Ground in Davisville, Rhode Island, Seabees worked to assemble strings of pontoons as Sock took shape throughout October 1943 in Narragansett Bay. When flight test operations commenced on 3 November, the field measured 312 pontoons long by 38 pontoons wide, 1,810 feet by 272 feet, composed of 10,072 T-6 5x7x5-foot pontoons and 219 T-7 5x7x7-foot pontoons. Sock drew only 1.5 feet of water and had 3.5 feet of freeboard. The field was moored by cables from barges attached amidships on either side of the structure. The cables joined up to a ring centered to three 15,000-pound anchors. Two massive outboard motors placed at diagonal corners allowed the field to swing about its center line into the wind with a minimum of tide or current effect.

Throughout the first week in November, aircraft from Air Group 14 successfully made 131 takeoffs and landings from Sock, all landing with 200 feet of runway to spare. Sock proved to be a competent airfield. The Navy conducted flight operations with modified carrier procedures, with one report noting how Sock offered the potential for more efficient deck operations than an Essex-class carrier.

Without arresting gear, aircraft could be landed quickly and the active field cleared more efficiently. The adjacent parking strip practically eliminated re-spotting operations and had room for a 90-plane group, with aircraft wings folded and the craft arranged in two fore and aft rows. British observers of the tests reported favorably to Churchill, who was keen to see Sock incorporated into the plans for Operation Overlord—the Allied invasion of Normandy.

Roosevelt, King, and particularly General Dwight D. Eisenhower saw things differently. The President and CNO thought the field unnecessary in light of the increasing number of aircraft carriers being commissioned. Eisenhower saw the field as unnecessary because of the proximity of airfields in England.

On 20 January 1944, Admiral Frederick J. Horne informed the British that the Americans would be disassembling Sock. Three days later, Eisenhower’s office advised the British against using it in Overlord. The next day, Churchill, although still expressing his belief in its use, acquiesced and endorsed Eisenhower’s position.

Today, Sock exists only in black-and-white photographs and film footage—and in the form of two small cardstock models stamped “CONFIDENTIAL,” which reside in storage at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. Dirty, smudged, and stained with fingerprints, once hinged by cellophane tape and thin thread, these are the very models that inspired Churchill to push for something bold and unique—the longest floating airfield, much less structure, ever constructed by the United States.

—Frank A. Blazich Jr., Curator of Modern Military History, National Museum of American History