By the mid-1930s, most scientists realized that the stars, including the Earth’s sun, radiate large amounts of nuclear energy. There was relatively satisfactory proof that very large amounts of energy were available if a suitable method for releasing and controlling it could be found.

“It” was discovered in 1938 by German researchers in the form of nuclear fission. They observed that when uranium atoms are bombarded with neutrons a few of the atoms will split in two parts, releasing tremendous amounts of invisible energy. The announcement of their discovery of uranium fission caused great excitement in scientific circles.

Dr. Ross Gunn and other physicists at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory soon began batting around ideas for “Buck Rogers”–type vehicles for air, land, and sea travel.1 They immediately recognized that here might be an answer to the major submarine propulsion problem—obtaining air for combustion in conventional power plants.

Nuclear fission was not combustion and thus did not require oxygen. But Dr. Gunn and his staff could not justifiably present such a concept before highly practical Navy bureau chiefs until more substantial evidence was in hand. It was not difficult for physicists to calculate that, if large numbers of uranium atoms were split in a short period of time, the amount of energy released would be far greater than could be obtained from any other source.

But thus far it was all theory—and somewhat unbelievable theory at that. Then, in early 1939, Columbia University’s Dr. George Pegram, one of the nation’s leading physicists, proposed to Rear Admiral Harold G. Bowen a meeting to discuss practical uses of uranium fission. Admiral Bowen was Chief of the Bureau of Steam Engineering, which had charge of the Naval Research Laboratory.

Dr. Pegram met with Admiral Bowen at the Navy Department in Washington on 17 March. Also present at the historic session were Dr. Enrico Fermi, the world’s leading expert on the properties of neutrons, who had come close to discovering uranium fission in 1934; Captain Hollis Cooley, head of the Naval Research Laboratory; and Dr. Gunn. The use of uranium fission to make a super-explosive bomb was discussed at the meeting. Fermi expressed the view that, if certain problems related to chemical purity could be solved, he considered the chances were good that a nuclear chain reaction could be initiated.

“Hearing these outstanding scientists support the theory of a nuclear chain reaction gave us the guts necessary to present our plans for nuclear propulsion to the Navy,” said Gunn. Three days later, on 20 March, Cooley and Gunn called on Admiral Bowen to outline their plan for a “fission chamber” that would generate steam to operate a turbine for a submarine power plant. Gunn told the admiral he had never expected to propose seriously such a fantastic program to a responsible Navy representative, but here was the proposal, and $1,500 was needed for research into the phenomenon of nuclear fission.

Admiral Bowen granted the funds—the first U.S. government money to be spent on the study of nuclear fission. That summer Gunn submitted his first report on nuclear propulsion for submarines—two months before the famed “Einstein letter” to President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposing the use of atomic energy in a bomb.

In his report, Gunn noted that such a power plant would not require oxygen, “a tremendous military advantage” that “would enormously increase the range and military effectiveness of a submarine.” But a host of problems had to be solved before a useful power-producing plant for a submarine could be constructed. No principles existed for the design of a power-producing nuclear reactor; indeed, many skilled physicists believed no nuclear reaction could be initiated outside the core of a star!

First, some large-scale method of uranium isotope separation had to be found. Not all uranium atoms are alike. Some are heavier than others. It was discovered that the lighter atom of uranium, with an atomic weight of 235, would undergo fission when bombarded with neutrons. The heavier U-238 atom more often would simply absorb a neutron and not split. The U-235 was found to be present in mined uranium at the ratio of only 1 to 140.

Subsequently, several institutions cooperated with the Naval Research Laboratory in the search for a feasible method of separating the elusive isotope. Beginning in January of 1941, Dr. Philip H. Abelson of the Carnegie Institution began working on the separation problem. That July, he joined the staff of the laboratory and together with Gunn developed a relatively simple and efficient method of separating the isotope. The Abelson-Gunn method was extensively tested and found to be entirely successful.

At about that time the Manhattan District—cover name for the atomic bomb project—took over priority and control of almost all fissionable material. Work on an atomic-powered submarine was brought to a virtual standstill.

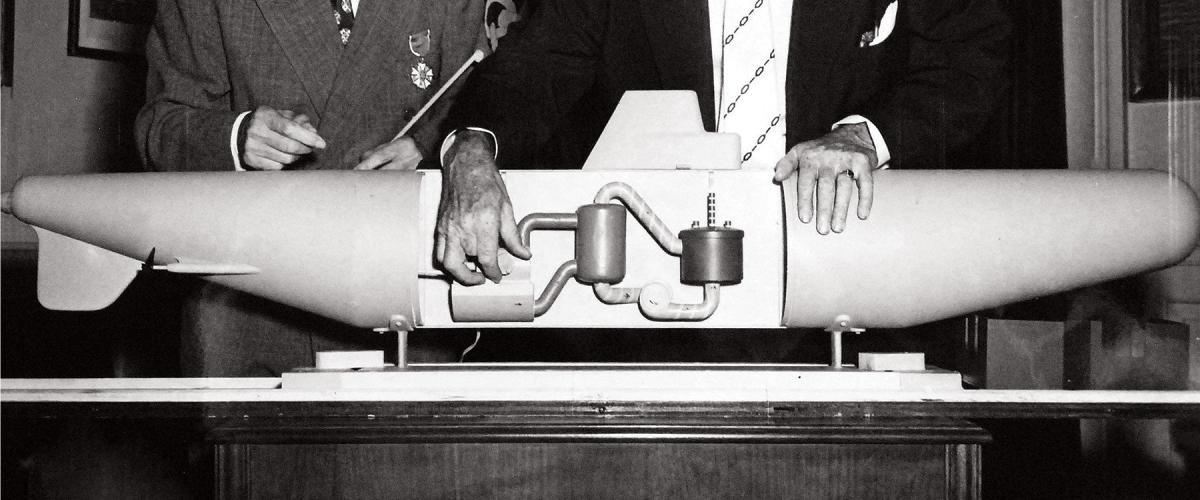

After initially rejecting the proven Abelson-Gunn separation procedure, the Manhattan District later adopted the method as “insurance” when the Manhattan-sponsored separation processes seemed in doubt. Some of the uranium isotopes used in the Alamogordo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki atomic bombs were processed by the Abelson-Gunn method. Two days after Japan surrendered in August 1945, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal presented Gunn and Abelson with Distinguished Civilian Service Awards for their role in the development of the atomic bomb.

After the war, Gunn also was given a $25-a-year raise, bringing his annual salary to $10,000, by law the highest amount that could be paid to a federal employee. Disgusted with the Navy’s lag in the field of nuclear propulsion, and tired of being given extensive responsibilities without a proportionate amount of authority, Gunn left the Naval Research Laboratory in 1947. He had served with the organization for two decades and at the time of his retirement simultaneously held the positions of superintendent of the Mechanics and Electricity Division, superintendent of the Aircraft Electrical Research Division, technical director of the Army-Navy Precipitation Static project, and technical adviser to the naval administration of the laboratory. He later joined the Weather Bureau, eventually becoming assistant chief.

Dr. Abelson had left the Naval Research Laboratory in August 1946 and returned to the Carnegie Institution because, after the war, “the Navy just wasn’t interested in nuclear propulsion.” He had enjoyed the excellent Navy cooperation with his scientific work in wartime but felt discouraged by the postwar letdown.

Interest in nuclear propulsion for ships was relegated to a minor position by the Manhattan project until August 1944, when a governmental committee was set up to make recommendations for the nation’s postwar policy for atomic energy development. That fall, the committee visited the Naval Research Laboratory.

In their visit report, Rear Admiral A. H. Van Keuren, then director of the laboratory, and physicists Gunn and Abelson urged the committee to give a nuclear-powered submarine high priority. The committee made its final report in December 1944: It recommended the government “initiate and push, as an urgent project, research and development studies to provide power from nuclear sources for the propulsion of naval vessels.”

The entire subject of atomic energy related to submarine and surface ship propulsion was considered in great detail when Gunn testified before the Special Committee on Atomic Energy established by the Senate. For the first time, the promise that atomic energy held for non-bomb purposes was brought to the attention of the average citizen: The New York Times of 14 December 1945 quoted Gunn saying that “the main job of nuclear energy is to turn the world’s wheels and run its ships.” The Times also mentioned the possibility of “cargo submarines driven by atomic power.” But the nation was at peace, and there was no longer a hurry for military-related progress.

In early 1946, the Navy was asked to participate in the construction of an experimental nuclear power reactor at the Oak Ridge, Tennessee, atomic research center. The Navy decided to send five officers to work on the Oak Ridge project. By coincidence, Captain Hyman G. Rickover, who was supervising the mothballing of ships on the West Coast, was in Washington at the time of the Oak Ridge invitation. Rickover reported to the Bureau of Ships (formerly the Bureau of Steam Engineering) that he had heard about research into the possibility of nuclear propulsion for ships and wished to apply for training in that area.

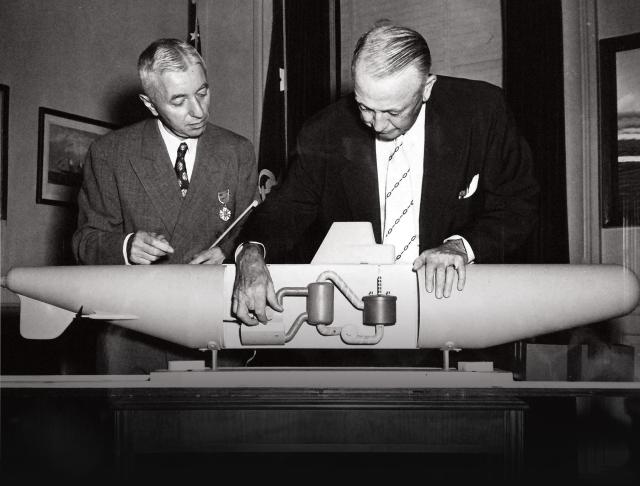

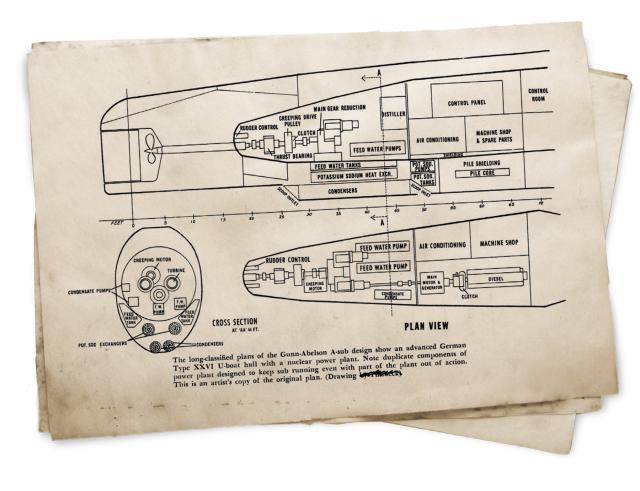

In December 1945, as a result of studies made by Gunn and his staff, Commodore H. A. Schade, who was then director of the Naval Research Laboratory, had proposed an elaborate nuclear shipbuilding research-and-development program. He also found a report written in the spring of 1946 by Abelson, who had obtained plans of the German Type XXVI submarine, a Walter-propulsion undersea craft designed for very high submerged speeds. Abelson “removed” the machinery of the Walter hydrogen-peroxide power plant and replaced it—on paper—with his conception of a nuclear propulsion plant.

Abelson’s report was an eye-opener. The report’s first paragraph contended “a technical survey conducted at the Naval Research Laboratory indicated that, with a proper program, only about two years would be required to put into operation an atomic-powered submarine mechanically capable of operating at 26 to 30 knots submerged for many years without surfacing or refueling. In five to ten years a submarine with probably twice that submerged speed could be developed [emphasis added].”

The 27-page report of the young physicist placed two “ifs” on the two-year timetable. There had to be sufficient priority given to the project by the Navy, the President, and the Manhattan Project; and the Navy effort had to be expanded to permit greater emphasis on Navy participation in design and construction of a uranium pile (reactor) of proper characteristics for this application. Abelson’s report continued:

It is estimated that the atomic submarine herein proposed could be improved in five to ten years such that it could operate for sustained periods at submerged speeds of forty to sixty knots or higher, using a jet propulsion system for propulsion. The development would require radical modification of hull design and many mechanical features that are at present untried, hence would require extensive research.

In his report, Abelson also told the “how” of building his proposed submarine power plant, which would use a potassium-sodium alloy as the heat transfer agent between the reactor and turbine. He proposed to mount the atomic pile and its shielding outside the pressure hull along the keel of the submarine. The submarine would have twin pumps and turbines so that, in the event of partial failure, it could continue operating at half power and at a speed of about 20 knots. But failure of the reactor was considered a remote possibility.

Quoting a recent report on atomic energy, Abelson noted:

The most striking feature of the pile is the simplicity of operation. Most of the time the operators have nothing to do except record the readings of various instruments . . . the pile performance of June 1944 considerably exceeded expectations. In ease of control, steadiness of operation, and absence of dangerous radiation, the pile has been most satisfactory.

There was prophecy in the report’s comment that a high-speed, atomic-powered submarine would operate at depths of about 1,000 feet, and “to function offensively, this fast submerged submarine will serve as an ideal carrier and launcher of rocketed atomic bombs.”

After reading the report, Captain Rickover, a former submariner, became obsessed with the idea of a nuclear-powered submarine. In the summer of 1946 at Oak Ridge, he began welding the four junior officers of the naval contingent into a team. The officers had been instructed to independently observe and report to Washington. However, Rickover quickly persuaded them to report to him. There was to be no question who was boss of the Navy group at Oak Ridge.

During the summer of 1946, while the Navy’s main interest in nuclear energy was directed into the Bikini atomic bomb tests, some contracts were awarded to commercial concerns for work on potassium-sodium metal alloys as a heat transfer in turbines, with possible nuclear application as an eventual goal. Also, the General Electric Company began to study the possibility of powering a destroyer-type ship with nuclear energy. Captain Harry Burris, originally named to the Oak Ridge group, became the Navy’s liaison officer to the General Electric project.

The Navy team sent to Oak Ridge began flooding the Bureau of Ships with almost weekly reports on various aspects of nuclear power. One memorandum stated that five to eight years would be required to develop and install a nuclear power plant in a ship given existing interest and effort in the project. However, the report predicted that as little as three years would be required if adequate funds and technical talent were made available.

After a year at Oak Ridge, Captain Rickover and his group began a survey of all work done to date in the nuclear propulsion field. In August 1947, while touring atomic installations in the United States, the group obtained the backing of Dr. Edward Teller, “father” of the hydrogen bomb, for nuclear ship propulsion.2

That fall, back in Washington, the group presented its report. But despite Dr. Teller’s backing, the Bureau of Ships would not follow its recommendations for an immediate speed-up of the naval reactor program. The group was disbanded, and Captain Rickover was scheduled to be sent to Oak Ridge as a document declassification officer. Vice Admiral Earle Mills, then Chief of the Bureau of Ships, agreed with most high-ranking officers in the bureau that there was not enough nuclear work to keep Rickover on in this area. However, he finally decided to let Rickover stay in Washington and made him a special assistant.

In that role, Rickover was assigned an office—next to a former ladies’ powder room into which his office soon overflowed—and given relatively few duties. However, he approached a group of scientists and engineers at Oak Ridge who were working on an almost stagnant reactor project and managed to interest them in a naval reactor. Few officials in Washington knew the significance of this change of emphasis, and those who did just did not publicize it.

The Atomic Energy Commission, which ran Oak Ridge, was startled to learn of the switch, but it felt it was better to have the scientists and engineers working on a naval reactor than on no reactor at all. Admiral Mills was impressed with the work of Rickover, his “electrical” wizard.

With a naval reactor in the works, Rickover set off to get official, top-level Navy backing for an atomic-powered submarine. He undertook to get the Chief of Naval Operations, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, to sign a memorandum urging immediate development of a nuclear-powered submarine. Two men who were destined to hold top positions in the nuclear-age submarine force—Captain (later Vice Admiral) Elton W. Grenfell and Commander (later Captain) Edward L. Beach—gave their support to the memorandum.

Admiral Nimitz, a former submariner, signed the memorandum as soon as it reached his desk. The document informed the Secretary of the Navy that the service believed a nuclear-propelled submarine was possible, was required, and, if given the proper emphasis, could be completed by the mid-1950s. Despite the favorable attitude of the Navy, the Atomic Energy Commission did not appear convinced of the necessity of a nuclear-powered submarine. However, Admiral Mills delivered a stinging public speech, blasting the commission for its lack of action, and subsequently the naval reactor study program was given formal approval.

The Bureau of Ships next signed a contract with Westinghouse for Project Wizard: the design and development of a power conversion system for submarines using high-pressure water as the heat exchanger between the nuclear reactor and turbine. Thus began the Navy’s second nuclear-propelled submarine project—the USS Nautilus (SSN-571).

1. N. Polmar, several discussions with Dr. Gunn at the Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, D.C., in 1962.

2. N. Polmar, discussion with Dr. Teller in San Antonio, Texas, 19 March 1995.