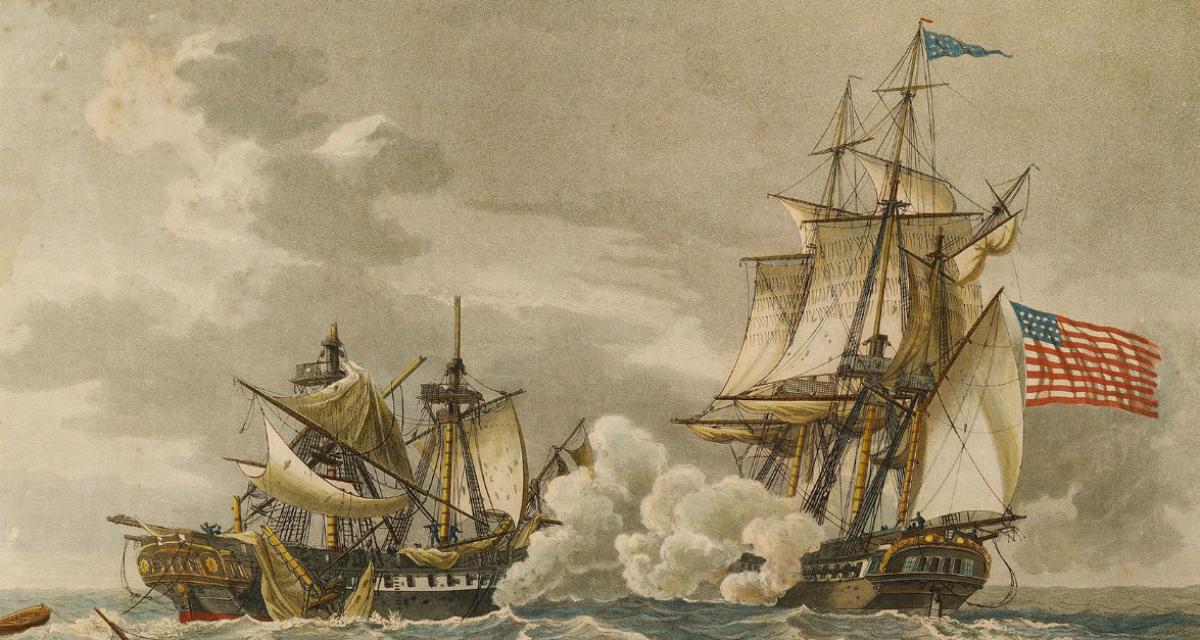

Before the animosity between Commodores James Barron and Stephen Decatur culminated in their fatal (for Decatur) duel, the two served together on board one of the U.S. Navy’s first warships, the frigate United States. The nation almost lost the frigate during the Quasi-War with France (1798–1800), and with her, a young wardroom and midshipmen mess that would define the U.S. Navy for the next half century. Barron would take Decatur’s life in 1820, but first he saved him and others of the pantheon of early American naval heroes.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

Captain John Barry commanded the United States during the Quasi-War. The conflict was confined mostly to naval engagements in the West Indies, where Barry and the frigate protected American commerce and fought French privateers. Barry earned the first captain’s commission in the U.S. Navy with his impressive Continental Navy record and more than 30 years of maritime experience. His brief time in the U.S. Navy brought fewer accolades. In time, he became known as the “Father of the U.S. Navy” for developing the young naval leaders that shaped the service for the next 50 years.

James Barron was one of Barry’s lieutenants on board the United States’ first cruise in 1798. Barron had every expectation for a life at sea from an early age. He and his older brother, Samuel, joined their father on board the merchant ships he commanded before the Revolutionary War. During the conflict, his father commanded the Virginia State Navy. Afterward, Barron apprenticed under his father until he received a lieutenant’s commission in the brand-new U.S. Navy in March 1798.

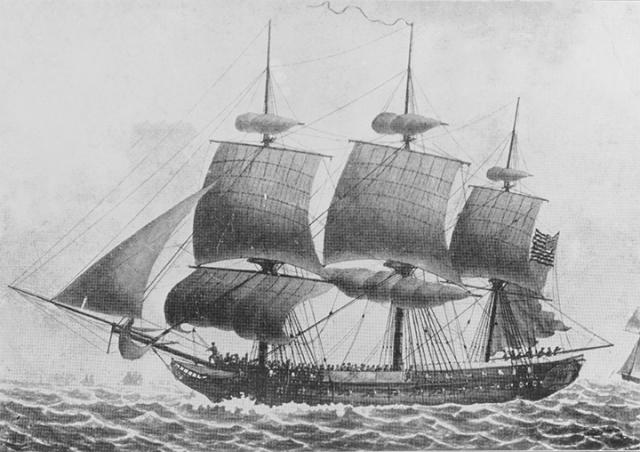

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

Barron was Barry’s third lieutenant, just ahead of Charles Stewart Jr. Barry also had an impressive midshipmen mess on board the United States. Because of his prestige, many fathers tried to gain midshipmen warrants for their sons to serve under Barry. Among his first midshipmen were Richard Somers and Stephen Decatur.

The United States left for her first cruise in July 1798. The frigate patrolled the West Indies for French privateers, but only sighted British warships and American merchants until late August. The United States eventually captured two French privateers: the San Pareil on 22 August 1798, and the Jalouse on 5 September.1 Spoiling provisions, inadequate ballast, prizes in tow, an overflow of prisoners, and an anticipated hurricane season convinced Barry to return to Philadelphia. The frigate's first cruise ended after only six weeks, but Philadelphia gave her a hero’s welcome.2

Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert, however, was not as pleased. He lamented to President John Adams, “Barry returned too soon—His reason, apprehensions from the Hurricanes in the West Indies at this Season.”3 Stoddert ordered Barry to refit immediately to get back out to sea before winter. On 1 October, Stoddert instructed Barry, “As this is the season when our vessels may be expected from Europe; And as it is probable attempts may be made by the French Cruisers to interrupt them on or near our Coasts, it becomes necessary that you proceed to sea as soon as your Ship is watered.” Stoddert wanted Barry “to protect the Trade from Delaware to New Hampshire,” until 15 November, when he should put into Newport, Rhode Island.4

Although brief, the frigate’s second cruise proved most disastrous. A powerful storm struck the United States within a day of departure. On 19 October, “Stiff gales, and rain” and “A heavy sea from the N.E.” forced the frigate south to avoid the growing tempest, but to no avail. Lieutenant John Mullowny noted in his log, “Ship pitching very much the sea running very high.”5 Conditions worsened the next day: “Very hard gales—A violent squall, Split the Fore Sail. . . . A very heavy head sea at ½ 4 P.M spring the Bowsprit.”6 The warm Gulf Stream winds softened the tar in the rigging, which slackened the shrouds and stays that secured the masts. A loose mast in such a storm could pound a ship apart, or snap and drag her down. The foremast started shifting and slamming against the keel like a hammer. Barry struggled to keep the United States before the wind while he tried to find a way to save his ship.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

Lieutenant Barron proposed a plan to secure the masts. As waves battered the hull and the wind howled around them, Barron climbed the shifting foremast with a team of topmen. Barron had a keen understanding of each rigging’s purpose and relation to the rest of the ship. From the undulating platform, they secured the foremast by fastening new lines to slack rigging from alternate sides to make them taut. Rain continued to pound down on them as the sun crept closer to the horizon. Once the foremast stabilized, Barron and his team proceeded with the same web-weaving operation on the main and mizzenmasts. After several hours in the rigging, Barron and the topmen descended in the darkness of the evening’s storm.7

Decatur, Somers, and the rest of the midshipmen not to mention the other young lieutenants, including Stewart, had never witnessed such an act of bravery and seamanship before. When Decatur first joined the United States, he struggled to learn the names of the various shrouds, stays, rigging, etc. He had to surreptitiously scrawl the names nearby.8 If Decatur or the others ever doubted the need for expertise in all aspects of seamanship, Barron quashed the idea. Barron was waterlogged and exhausted when he came down, but the young officers of the United States likely looked awestruck at him.

Barron saved the ship from immediate peril, but the storm was not finished. On 21 October, ballast broke loose and killed a Marine.9 When the storm finally abated on 25 October, the United States started to limp back to Philadelphia for repairs.10

When Secretary Stoddert asked Barry for promotion recommendations, he responded, “my third Lieutenant James Barron, is as good an Officer and as fit to command as any in the service, and I hope when you do promote him, you will give him a Ship that will enable him to do credit to himself and honor his country.”11 Barron was promoted to captain in May 1799. He first served as Barry’s flag captain in the United States and then took his own command, the sloop-of-war Warren in September 1800. He later served as the Mediterranean Squadron commander in 1806. He commanded the frigate Chesapeake on 22 June 1807 when the British frigate HMS Leopard opened fire after Barron refused to let the British search the Chesapeake for deserters. He was unprepared for action and was forced to surrender. Stephen Decatur was a member of the court-martial that reviewed the incident and suspended Barron for five years. Afterward, Decatur became one of Barron’s greatest critics. The bitterness led to the duel that ended Decatur’s life on 22 March 1820.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

The U.S. Navy would have survived without Barron’s daring act to save the United States, but without some of the service’s earliest heroes. During the First Barbary War, Richard Somers trained and commanded many of the gunboat crews that fought in Tripoli Harbor. He died when attempting to destroy the Tripoli Harbor defenses with the infernal Intrepid. Stephen Decatur secured his place in U.S. history when he destroyed the captured frigate Philadelphia during the First Barbary War. He returned to the United States as her captain in 1810 and defeated the British frigate HMS Macedonian during the War of 1812. After the war, Decatur’s squadron won the Second Barbary War and forced lasting treaties with the Barbary States. Charles Stewart also distinguished himself in the First Barbary War and the War of 1812, but his greatest impact to the U.S. Navy may have been his 62-year-long career. He influenced naval policy up to the start of the Civil War. Because of Stewart, Decatur, and Somers’ impact on the U.S. Navy, the loss of the United States could have had compounding effects for the service. Barron’s work in the rigging of the imperiled United States was a daring act of leadership, bravery, and seamanship that saved more than just his ship.

(Naval History & Heritage Command)

1. Journal of Lieutenant John Mullowny, 23 August 1798, in Naval Documents Related to the Quasi-War with France: Naval Operations from February 1797 to December 1801, 7 vols. [hereinafter cited NDQW], Dudley W. Knox, ed. (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1935–38), I: 331; Journal of Lieutenant John Mullowny, 5 September 1798, in NDQW, I: 377.

2. Tim McGrath, John Barry: An American Hero in the Age of Sail (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2010), 456–65.

3. Secretary of the Navy to President John Adams, 21 September 1798, in NDQW, I:430.

4. Secretary of the Navy to Captain John Barry, 1 October 1798, in NDQW, I:481–82.

5. Journal of Lieutenant John Mullowny, 19 October 1798, in NDQW, I:551.

6. Journal of Lieutenant John Mullowny, 20 October 1798, in NDQW, I:551.

7. James Tertius de Kay, A Rage of Glory: The Life of Commodore Stephen Decatur, USN (New York: Free Press), 28–29.

8. Ibid, 22.

9. Journal of Lieutenant John Mullowny, October 21, 1798, in NDQW, I:552.

10. Journal of Lieutenant John Mullowny, 25 October 1798, in NDQW, I:562.

11. Captain John Barry to the Secretary of the Navy, 16 March 1799, in NDQW, II:474.