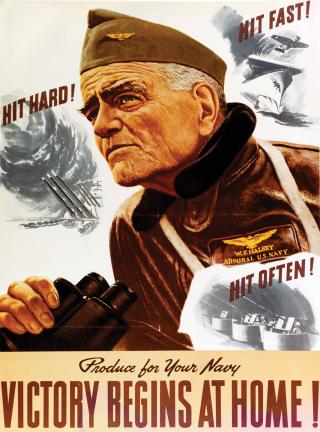

Admiral William F. Halsey Jr. fought the Empire of Japan from 7 December 1941 until 15 August 1945. In those 45 months—from his task force’s early strikes against Japanese island bases to the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo to command of the Third Fleet through V-J Day—he became America’s favorite admiral.

Often lost between the Pearl Harbor and Tokyo Bay bookends is Halsey’s shore-based command from late 1942 until early 1944. As Commander, South Pacific Force (ComSoPac), he proved an effective, often innovative leader.

By then, Halsey nursed a boiling, ten-month hatred for Japan; Pearl Harbor had chiseled an indelible impression on his psyche. Riding the USS Enterprise (CV-6) into port the night of 8 December, pushing through oil-scummed water, he saw the sights and smelled the odors. They became a scarlet thread in the tightly woven tapestry of his brain.

When he became ComSoPac in October 1942, Halsey wasted no time establishing priorities. Days after arriving at Nouméa, New Caledonia, he directed that naval officers could dispense with their neckties, not merely because of the tropical atmosphere, allegedly saying, “You’re going to be too busy to use the damn things.”1

‘A Real Old Salt’

Halsey was born into a naval family in 1882 and, like so many Navy juniors, followed the same path as his father, graduating in the U.S. Naval Academy class of 1904, standing 42nd in a class of 62. His Lucky Bag yearbook entry described “A real old salt. Looks like a figurehead of Neptune. Everybody’s friend . . .”2

Subsequently, Halsey accumulated an enormous amount of seagoing experience. His service included the USS Missouri (BB-11), an ironic twist considering that the later Iowa-class Missouri (BB-63) would become his Third Fleet flagship in the Pacific war. From 1909 to 1932 he was captain of five destroyers, commanded three destroyer divisions, and became executive officer of the battleship Wyoming (BB-32). His shore billets included naval intelligence, Annapolis, and attaché duty in Europe during the 1920s.

Halsey became a naval aviator in 1935 at the advanced age of 52. He had chosen the path to pilot rather than the simpler aviation observer rating, which also would have qualified him for carrier command. Shortly thereafter the former destroyer sailor assumed the conn of the USS Saratoga (CV-3) and rose to rear admiral in 1938.

In the six months after Pearl Harbor, “Bull” Halsey ran nearly nonstop. The pace caught up with him: Beached with severe psoriasis from June to September 1942, he missed the Battle of Midway. That summer he told an Annapolis audience that it was “the greatest disappointment of my career.”3 Upon release in September, Halsey received orders from Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester Nimitz to proceed to the Solomon Islands, eventually to command the South Pacific Area.

He was en route the following month when CinCPac bumped up the schedule. Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley’s lackluster performance in the struggle for Guadalcanal had convinced Nimitz to confirm Halsey’s advancement on arrival. It was an awkward situation, as Halsey and Ghormley had been Naval Academy football teammates. (Navy lost to Army 22-8 in 1902 and 40-5 in ’03. In Halsey’s last year, Army skunked the Middies 11-0.)

As Halsey noted in his postwar memoir, “Jesus Christ and General Jackson! This is the hottest potato they ever handed me!”4

Though Halsey nurtured doubts about his suitability, for many of the men in his new command, the Bull’s accession was electric. Lieutenant Commander Roger Kent, a Guadalcanal intelligence officer at Henderson Field, recalled: “Then we got the news: the Old Man had been made ComSoPac. I’ll never forget it. One minute we were too limp with malaria to crawl out of our foxholes; the next minute we were running around whooping like kids.”5

Betwixt Nimitz and MacArthur

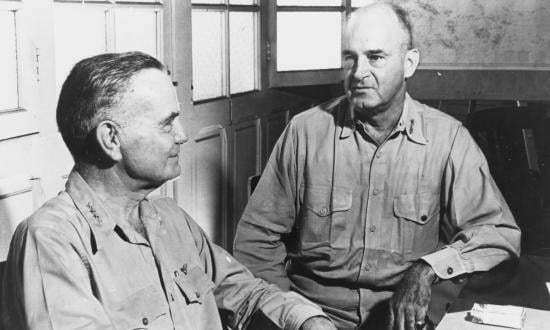

As South Pacific Area commander, Halsey was responsible for much more than Guadalcanal. While the island necessarily remained his focus, he inherited a vast area east of the 160th meridian.

Halsey served two masters. General Douglas MacArthur was overall Southwest Pacific commander, but the Joint Chiefs granted Halsey tactical control in the Solomons. As he said: “Although this arrangement was sensible and satisfactory, it had the curious effect of giving me two ‘hats’ in the same echelon. My original hat was under Nimitz, who controlled my troops, ships, and supplies; now I had another hat under MacArthur, who controlled my strategy.”6

ComSoPac was necessarily a joint organization. Halsey reflected, “Our Army, Navy, and Marine airmen in the Solomons fought with equal enthusiasm and excellence under rear admirals, then under a major general of the Army, and finally under a major general of Marines.” The latter was Ralph J. Mitchell, who succeeded Nathan Twining (sent home by Halsey for a rest), but Air Forces General Henry Arnold “kidnapped” Twining and sent him to command the 15th Air Force in Italy.7

By instinct and experience, Halsey favored the offense. He vowed to retain that aggressive posture “as long as I have one plane and one pilot.”8

Fortunately, Halsey had a strong staff that remained remarkably consistent throughout the war. The longest-serving was Lieutenant Herbert C. Carroll, from June 1940 to November 1945. Others included Commander H. Douglas Moulton, flag secretary from 1941 to August 1943 and air ops until late 1945. Captain Leonard J. Dow handled communications until V-J Day. Captain Harold E. Stassen was flag secretary in the last two years of the war except for detached duty with the United Nations.

One of Halsey’s long-term courtiers was chief of staff Captain Miles Browning. Contemporaries considered him smart, erratic, and opinionated, but he had Halsey’s confidence from before the war. Though notably unpopular, he achieved carrier command in mid-1943, being dismissed after a series of faults in mid-1944.

Rear Admiral Robert B. Carney succeeded Browning in July 1943, remaining all the way to Tokyo Bay.

Halsey probably relied more on his staff than most equivalent commanders, and the team came to recognize his moods. Never a micromanager, often he proved inattentive to details but enjoyed his splashy public reputation. As a convivial, enthusiastic drinker, he could be profane and narrowly focused. Apparently, he had no outside interests.

Halsey’s biographer E. B. Potter considered him “a probabilities man, that is, he tended to make up his mind what the enemy would probably do and acted accordingly. In this respect, as well as in his liking for publicity, Halsey was in the Nelsonian tradition.”9

Instincts Honed

Whatever his foibles, as ComSoPac, Halsey quickly got down to business. In a meeting with Guadalcanal’s Marine Corps commander, Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, Halsey asked if the leathernecks could hold. Vandegrift thought that they could, given adequate support. Halsey replied: “All right. I’ll promise you everything I’ve got.”10

After ten months of war, Halsey’s professional instincts had only sharpened. He saw the clash as a gut-level conflict and ordered his priorities accordingly. Reportedly, shortly after landing at Nouméa, he declared: “If it helps kill Japs it’s important. If it doesn’t help kill Japs it’s not important.”

Within days of Halsey’s arrival, the Imperial Japanese Navy and Army launched a rare combined operation, a truly joint effort to secure Guadalcanal once and for all. While the Japanese Army strove to capture Henderson Field, Emperor Hirohito’s “sea eagles” rose from four carriers to the north. The result was the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands.

The American commander’s exhortation to his forces was vintage Halsey: “Strike, repeat, strike!”11

The carrier engagement on 26 October, just before Halsey’s 60th birthday, resulted in an American tactical defeat: The USS Hornet (CV-8) was sunk and the Enterprise damaged in exchange for damage of two Japanese flattops. But the outcome benefited the larger campaign since events at sea did not alter the situation ashore. Henderson Field remained under management of the U.S. Marines, and Japanese aircraft losses gave the Americans air superiority in the subsequent showdown.

As the sanguinary campaign approached its peak, Halsey committed as many assets as he could scrape together—land, sea, and air. It proved barely enough. The slugfest known as the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was fought and won on 12–15 November (see “Guadalcanal Quintet,” October 2021, pp. 12–19). The combined surface and air action was costly for both sides: nine American warships and 36 aircraft vs. two Japanese battleships, four other warships, 11 transports, and 64 aircraft.

But the three-day and -night clash cost the lives of Rear Admirals Daniel C. Callaghan, in the USS San Francisco (CA-38), and Norman Scott, on board the Atlanta (CL-51), by friendly fire. Halsey especially mourned the latter: “I had known and loved Norm Scott for years; his death was the greatest personal blow that beset me during the whole war.”12

However, Tokyo finally had enough: Within weeks, the Emperor’s forces began seeking to extricate themselves from the Guadalcanal sinkhole.

Halsey became a full admiral on 18 November, four weeks after assuming command. At month’s end he appeared on the cover of Time magazine (and would again in July 1945).

In a New Year’s Eve meeting with correspondents, Halsey noted that the Japanese were being forced back and irrationally predicted that U.S. forces would be in Tokyo by year’s end. (Later he stated that he made the comment to bump up morale in his command.)13

Halsey and some staffers flew to New Zealand in early January, showing the flag in Auckland for Prime Minister Peter Fraser. The admiral repeated his Tokyo claim, noting the Allies had 363 days to make it a reality.

Upon return to Nouméa, on 9 February 1943 Halsey received a message from Army Major General Alexander M. Patch: “Total and complete defeat of Japanese forces on Guadalcanal effected 1625 today. . . . Am happy to report this kind of compliance with your orders . . . because Tokyo Express no longer has terminus on Guadalcanal.”14

Leapfrogging Toward Rabaul

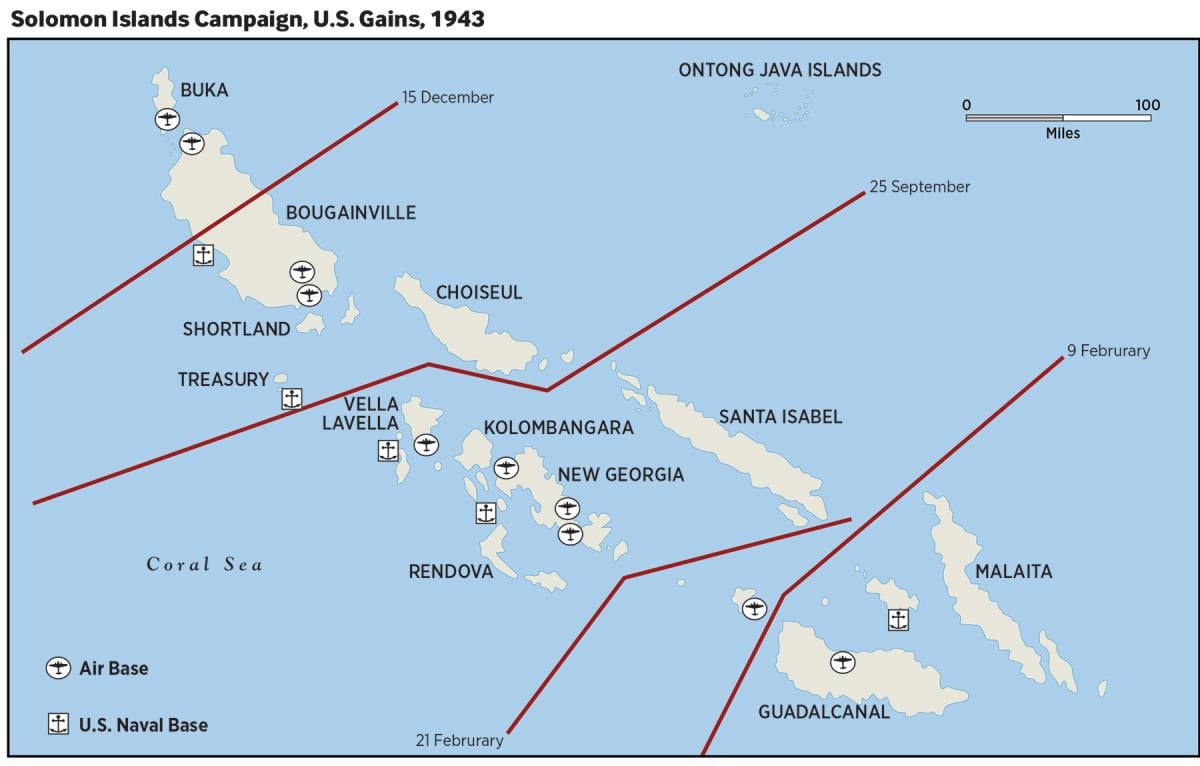

Halsey lost little time shifting to offense, launching an unopposed landing in the Russells on the 21st, some 50 miles northwest of Guadalcanal. The move was calculated to interdict enemy sea and air movement closer to New Georgia, which blocked the way to Bougainville. And beyond Bougainville lay the ultimate prize: Rabaul, New Britain, site of a major Japanese base with five airfields and an excellent harbor. (Isolated and bypassed, it would remain in Japanese hands until V-J Day.)

Halsey became an early practitioner of island-hopping. After the bloody campaign on New Georgia, he executed the first “leapfrog” when he bypassed Kolombangara for Vella Lavella. It was a major contribution to American strategy, and Douglas MacArthur took note. Although the concept had been discussed previously, Halsey was the one who made it a reality. It was perhaps the best example that he could be more than an instinctual fighter.

In June 1943, Halsey kicked off Operation Cartwheel, the umbrella for nearly a dozen subsequent landings lasting into the new year. They included Operation Toenails, aimed at the New Georgia group. But coordination with MacArthur’s affiliated plans required Halsey to back up his schedule until the end of June. Landing at Rendova on the 30th netted another step closer to the central Solomons golden ring—Munda Airfield on New Georgia. As always, the enemy cast his vote: Instead of the 30-day campaign Halsey’s staff envisioned, Toenails stretched to four times that long, with four Army divisions augmented by Marine Corps units.

Still headquartered in Nouméa, New Caledonia, Halsey directed Operation Cherryblossom to launch against Bougainville on 1 November. A distraction was provided by New Zealanders who landed in the Treasuries in late October 1943 while U.S. Marines raided Choiseul in the Solomons.

Bougainville’s airfields lay in range of the Japanese fleet bastion at Rabaul. Army bombers frequently attacked Rabaul, but the Joint Chiefs wanted Allied fighters and medium bombers available. The Torokina field, completed in six weeks, was only about 200 miles southeast of Rabaul.

Rabaul continued drawing a succession of air strikes. Halsey’s tailhookers launched from two carriers on 5 November and five on the 11th, made possible by rotating combat air patrols from land-based fighter squadrons within range from Barokoma. Despite poor weather and heavy opposition, on Armistice Day the aircrews pressed their attacks, claiming 25 planes downed against five of their own. They reckoned damage to six cruisers and two destroyers.

Tokyo had its own take on the results: destroying 200 of 230 American planes while sinking two carriers and four cruisers.15

Some accounts vary, but generally in both strikes the aviators are credited with damaging seven cruisers and four destroyers plus one destroyer sunk.16

In December Halsey was ordered to Pearl Harbor to confer with Nimitz, thence to Los Angeles to meet with industrialists, proceeding to Washington and discussions with Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King. But first, Halsey detoured to Brisbane to take leave of MacArthur. The generalissimo astonished the admiral by offering him command of all Allied naval forces for unspecified upcoming operations. Ever the politician, MacArthur wanted an American admiral senior enough to outrank the British. As Halsey summarized, “I told King and Nimitz about his offer . . . and that’s the last I heard of it.”17

‘Ten Feet Tall and Bulletproof’

Following his Hawaii stop, Halsey flew to San Francisco, where he was reunited with his wife Frances for the first time in 16 months. It was also Halsey’s first meeting with “Bill III’s” return from days adrift following a plane crash in August.18

The Battle of Vella Gulf set a pattern. From 6 August through 26 November the Americans lost one destroyer while putting nine Japanese men-of-war on the bottom. Tassafaronga on 1 December traded the light cruiser USS Northampton (CA-26) for an enemy destroyer. But clearly, surface warriors prospered under the leadership of Rear Admiral Aaron S. “Tip” Merrill and Captain Arleigh “31 Knot” Burke.

Halsey remained at the helm of the South Pacific theater until early 1944, occasionally coordinating with MacArthur’s adjoining Southwest Pacific theater. The two commanders would work together again, and not entirely for the best.

Halsey received the Army Distinguished Service Medal for the period 8 December 1942 to 1 May 1944. “As a result of Admiral Halsey’s conduct of command, the Army forces in the South Pacific Area were splendidly cared for and were able to accomplish the combat and logistic mission assigned in the most effective manner.”19

Wanting to see the war for himself, in March Halsey flew to Bougainville for a look at two Army divisions fighting there. He observed progress toward the Piva airstrip when, “as usual, paying no attention to where I stepped,” he tripped over the protruding foot of a Japanese corpse. The admiral quipped, “He was the only Jap who brought me to my knees.”20

After a passive April, in May Halsey returned to the United States to confer with King and Nimitz, learning that he would command the Third Fleet. But SoPac remained close under the skin, and Halsey embarked on a farewell tour of his realm, visiting New Zealand and several of the bases seized in hard-fought battles by soldiers and Marines. He noted that only the cemeteries marked the passage of battle.

On 15 June, Halsey turned over command to Vice Admiral John H. Newton, previously SoPac deputy. Three days later, Halsey assumed command of the Third Fleet. He established his shore base in Hawaii as Admiral Raymond Spruance’s Fifth Fleet smothered the Marianas.

For the remainder of the Pacific war, Halsey’s Third Fleet alternated with Spruance’s Fifth in offensive operations. But Halsey’s future was spotty. His flawed performances at Leyte Gulf in October 1944 and “Halsey’s Hurricane” in December cost the Navy seven ships and nearly 1,500 men, yet he retained command. To relieve him seemed unthinkable to the Washington and CinCPac gurus; politically, the Bull appeared ten feet tall and bulletproof.

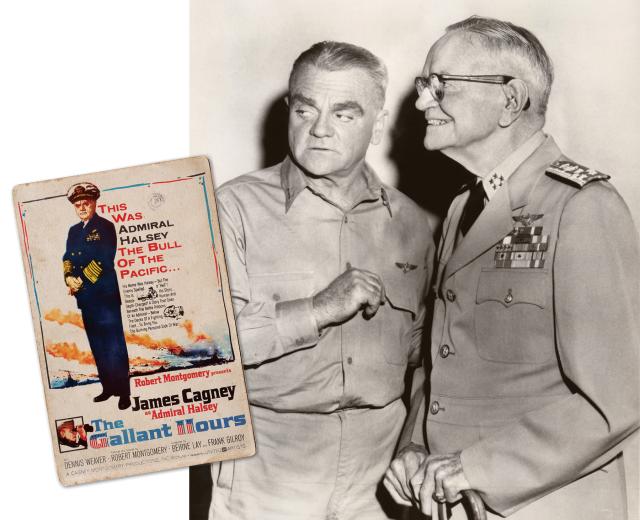

Halsey retired in 1946 and died in 1959. He probably remains best known to the public from numerous movie portrayals, but only one of his eight cinema appearances addressed his Solomons tenure: The Gallant Hours, a convoluted 1960 account of the admiral’s 1942–43 period. Despite the mish-mash of overlapping chronologies, connoisseurs consider Cagney’s portrayal definitive almost in the way Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet is considered definitive.

Cagney coproduced the film with director Robert Montgomery, a wartime lieutenant commander. Former naval aviator Dennis Weaver (better known as Gunsmoke’s Chester) and merchant mariners Richard Jaeckel and Harry Landers were featured in the cast.

The other Halsey movie portrayals included those of James Whitmore (1970’s Tora! Tora! Tora!), Robert Mitchum (Midway, 1976), Kenneth Tobey (MacArthur, 1977), Richard X. Slattery (The Winds of War, 1983), Pat Hingle (War and Remembrance, 1988), and Glenn Morshower (Pearl Harbor, 2001); none of those actors resembled Halsey. Dennis Quaid was more credible in the 2019 Midway remake.

In The Gallant Hours, Halsey’s valet is Chief Petty Officer Manuel Salvador Jesus Maravilla (played by Leon Lontoc), who is not mentioned in Halsey’s memoir. According to the script, Maravilla was a 28-year veteran retiring the same day. Preparing for the retirement ceremony, Halsey asks, “What do you remember best?”

Maravilla replies, “I can remember the Gilbert Islands, Marshall Islands, the Tokyo raid, Kwajalein and so many others whose names I cannot remember. But the one that will always stay clear in my mind . . . Guadalcanal.”

Certainly, “Cactus” was the cornerstone of Halsey’s SoPac tenure.

1. Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account (New York: Penguin, 1992), 335–36.

2. The Lucky Bag (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Academy, 1904), 41.

3. E. B. Potter, Bull Halsey (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1985), 150.

4. William F. Halsey and J. Bryan III, Admiral Halsey’s Story (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1947), 109.

5. Halsey and Bryan, 116.

6. Halsey and Bryan, 154.

7. Halsey and Bryan, 186.

8. Potter, Bull Halsey, 221.

9. E. B. Potter, “The Command Personality,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 95, no. 1 (January 1969): 19–25.

10. Halsey and Bryan, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 117.

11. Historians Richard B. Frank, John Lundstrom, and James Hornfischer cite the quote as, “Strike, repeat, strike!” Halsey’s memoir (p. 121) has it as, “Attack repeat attack!”

12. Halsey and Bryan, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 127.

13. Halsey and Bryan, 142.

14. Frank, Guadalcanal, 597.

15. Halsey and Bryan, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 183.

16. U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific), Naval Analysis Division, The Campaigns of the Pacific War (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1946), 171.

17. Halsey and Bryan, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 186.

18. Halsey and Bryan, 187

19. “William Frederick Halsey, Jr., 30 October 1882–16 August 1959,” Naval History and Heritage Command.

20. Halsey and Bryan, Admiral Halsey’s Story, 191.