On 5 November 1915, Lieutenant Commander Henry C. Mustin made history when he made the first underway catapult launch from a ship, the USS North Carolina (ACR-12) in the Curtiss Model F flying boat AB-2—experimental work that ultimately led to the use of catapults today. Several months before, though, trials of the device were undertaken using a less auspicious craft—Coal Barge No. 214.

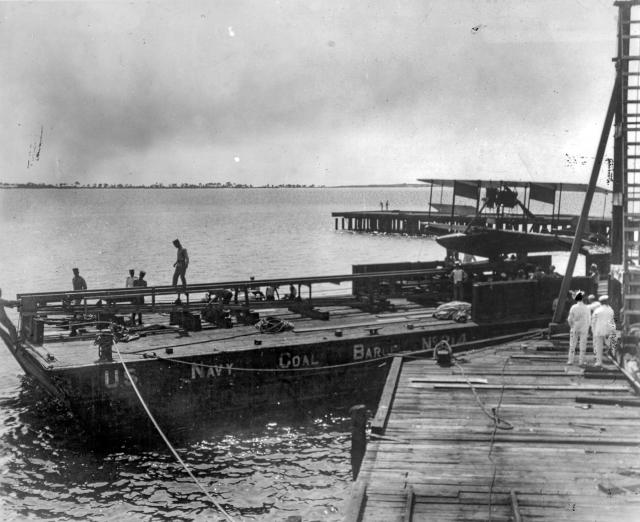

Construction of the 170-ton, 110-foot by 30-foot barge was authorized by the Bureau of Construction and Repair on 2 November 1907. Work began at the Norfolk Navy Yard early in 1908, and the barge was launched on 16 May 1908 along with other barges built simultaneously. It was a simple construction—wood, sheathed with copper, and fitted with flashboards on top to increase its hauling capacity. It was sent to Key West, Florida, for service, where it presumably provided the vital fuel that powered the ships of the steel navy that propelled the United States onto the world stage a decade before.

But the future was looming. The Navy had been searching for a launching device that would allow men-of-war to operate aircraft from their decks at sea. Though several designs were tried, a compressed-air catapult seemed the most promising.

Trials were held in Annapolis in the summer of 1912; the catapult was installed at the end of Santee Dock.

The first attempt by Lieutenant Theodore G. Ellyson ended with the aircraft crashing head-on into the water; obviously some adjustments still needed to be made.

After some refinements, the catapult device was mounted onto a small barge just two feet above the waterline. In tests held on 12 October 1912 at the Washington Navy Yard, Ellyson successfully launched his hydroaeroplane with the catapult.

Further tests throughout 1913 insured the device's reliability, and after some redesigns it was completed. It was boxed up and sent—along with the men, equipment, and aircraft of the Naval Aviation Camp at Annapolis—in the USS Mississippi (BB-23), reactivated in January 1914 to act as an aviation support ship, down to Pensacola, Florida, to the newly-established Naval Air Station Pensacola.

Little was done catapult-wise in 1914—the occupation of Veracruz, Mexico, taking up much of the aviator's time and attention. The Mississippi, meanwhile, was sold to Greece. In 1915, work began anew and trials were resumed. Without a dedicated support ship, the aviators had to find something with which they could test their setup. They turned to Coal Barge No. 214, which had been stationed in nearby Key West.

The barge was fitted up with the catapult and track, and by 26 April 1915 it was ready for testing. Lieutenant Patrick N. L. Bellinger was to have the honor of testing the setup that day—the first test like it since 1912.

He was at his best. Hungover, he vomited twice before climbing into the cockpit of the Curtiss Model F flying boat, designated AB-2. He taxied the flying boat over to the coal barge and the aircraft was hoisted up and placed on the track.

As Bellinger gunned the engine, the barge was pointed into the wind. The catapult was fired. "There was a glorious feeling," he later recalled. "Everything worked beautifully. As as soon I was in the air, I was a well man."

The test proved so successful that the catapult was mounted onto the armored cruiser North Carolina, recently overhauled to fill the roll that Mississippi once occupied. Arriving on 9 September 1915, would be the cruiser from which Mustin would be catapulted into history. The future had arrived on fabric and wooden wings.

But what of Coal Barge No. 214? In 1916, it was noted that it had been "fitted with [a] catapult for aeroplanes." Likely, it was still used for testing. But after the First World War, it disappeared. Perhaps it was sold, or scrapped. By 1920, many of its sister barges had been converted for other uses, and thereafter were redesignated as "open lighters" to carry other types of cargo. Coal had given way to oil and gasoline as the fuels of the future, and so too had Coal Barge No. 214. While it may be gone, its legacy lives on in the carrier aviation of today.