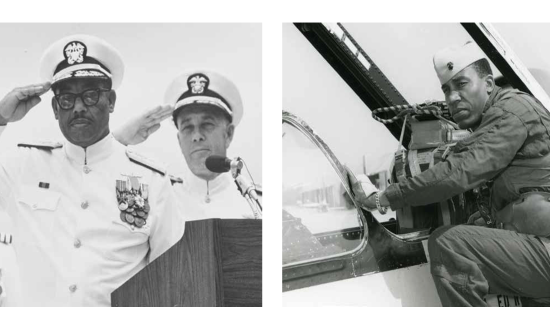

This Saturday, 14 May, the U.S. Navy will commission the guided-missile destroyer USS Frank E. Petersen Jr. (DDG-121), named for Lieutenant General Frank Peterson, U.S. Marine Corps, the first black Marine aviator. The commissioning will take place in Charleston, South Carolina, and the ship’s home port will be Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii.

The ship’s crest bears the motto “Into the Tiger’s Jaw,” a phrase General Petersen often used. The Naval Institute Press book, Into the Tiger’s Jaw: America’s First Black Marine Aviator, is his inspiring autobiography. The following is an excerpt from the preface and prologue:

During World War II, blacks learned, again, that fighting for their country brought them no closer to full citizenship. Trying to enlist, they were often summarily rejected. The Army accepted them only in a quota system linked to the proportion of the black population of the country, and then only in segregated units whose roles were primarily noncombatant in nature, except for certain “special” Army Air Forces units like the Tuskegee Airmen, set up only in response to civil rights campaigns.

These were regarded as an “experiment” and were not expected to last. Contrary to expectations, these units distinguished themselves in combat. Many of the men involved died. Generally, however, historical patterns show that blacks were usually allowed to serve only in times of crisis, when manpower needs surmounted the restrictions of racism.

In I948, President Harry Truman issued an edict to the armed forces requiring integration. Blacks would be given equal opportunity. They were to enjoy the same advantages and opportunities to perform as their white counterparts. Blacks then on active duty viewed the pronouncement with elated optimism, but others moaned in sardonic cynicism, recalling that actions, not words, were the measure of progress.

When President Truman issued his edict, the Marine Corps, of all the services, was in the least enviable position for compliance. Not until May 1942 had it finally succumbed to political and public pressure and officially accepted blacks into its ranks for the first time in its 150-year history. It was the last of the services to do so. The first black Marines underwent segregated training at the Montford Point Marine Base, part of the massive Camp Lejeune Training Base. Initially assigned for duty to a composite defense battalion (a small, self-sufficient army that employed a maximum number of special skills ranging from infantryman to radar technician), the first recruit, Private Howard Perry of Charlotte, North Carolina, arrived for duty on 26 August 1942. By the middle of September, 125 new black recruits were undergoing training under the leadership of white enlisted and officer personnel. Commanding was Colonel Samuel A. Woods, who later wrote to the director of Marine Corps recruiting:

Thank you for getting us some excellent recruits. They are most enthusiastic, and I am sure they are doing their level best to make good. We have to train the organization to operate, maintain, and repair the equipment that belongs to the Composite Battalion; therefore, we have to run our own schools. The men recruited have in general shown splendid aptitude for the service; at present we have probable rejections, but so far none of these has been for inaptitude.

After the blacks passed their trial period, plans were immediately made to bring more blacks into the Corps and to form more black units. By 1949, blacks in the U.S. Marine Corps numbered 1,633 enlisted and no officers on deck. By 1951 there were three black officers in the Corps, and by the end of 1967 officers numbered 314 with 23,046 black enlisted. (It is noteworthy that the number of black officers grew extremely slowly. Fred Branch, the first black to become a commissioned officer in the Marine Corps, was summarily discharged into the reserves the same day he was commissioned in 1945. As will be seen, the scaling down of the Corps after World War II dictated that the 245 men in his officers’ candidate class were simply not needed.)

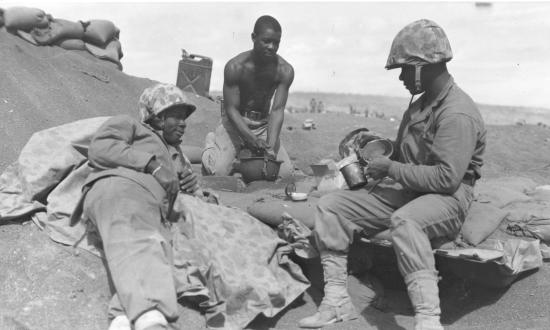

However, during World War II, a total of 19,168 blacks served in the Marine Corps. Of this number, approximately 13,000 served in overseas combat commands. The 52d Defense Battalion was organized on 15 December1943. It saw service on Roi and Namur Islands, Kwajalein, the Marshalls, and Guam before returning to the States in 1946. There were a total of 20 such defense battalions in the Corps. The two black battalions (the 51st and 52d) were the last formed.

As the United States began to achieve dominance in the Pacific, the Marine Corps’ need for logistics personnel supplanted the need for combat troops. Blacks were trained in logistics handling skills and formed into 12 ammunition-handling companies as part of the beach parties used in amphibious landings. Beginning with the Marine landing on Saipan, these ammunition companies took part in every major landing thereafter. The first black Marine to die in combat was Private First Class LeRoy Seals of Brooklyn, New York. He received fatal wounds shortly after the Saipan landing on 16 June 1944.

A future Marine commandant, General Lemuel C. Shepherd, then commanding the 41st Provisional Marine Brigade, took the opportunity to praise the 4th Ammunition Company:

“You are commended for the splendid and expeditious manner in which the supplies and equipment were unloaded from the LSTs’ group. Working long hours frequently during nights and in at least two instances under enemy fire [you] so coordinated your unloading [ that supplies kept] flowing to the beach. You have contributed in large measure to the successful and rapid movement of combat amphibious operation.”

General Shepherd was not alone in praise of the black Marines. General A. A. Vandegrift, then Commandant of the Marine Corps, noted: “The Negro Marines are no longer on trial. They are Marines—period.” Major General William Rupertus, then commanding the 1st Marine Division, commended the 7th Ammunition Company for its action on Peleliu:

“The performance of the officers and men of your command throughout the landing on Peleliu and the assault phase has been such as to warrant the highest praise. Unit commanders have repeatedly brought to my attention the wholehearted cooperation of each individual. The Negro race can well be proud of the work performed by the Seventh Ammunition Company as they appreciate the privilege of wearing a Marine uniform and serving with the Marines in combat. Please convey to your command these sentiments and inform them that in the eyes of the entire 1st Marine Division, they have earned a well done.”

In spite of these commendations based upon their performance in combat environments, blacks were still not allowed to serve in infantry divisions or Marine air units. There were no black women Marines or officers. As World War II drew to a close, the Marine Corps redefined its manpower requirements and restricted the number of blacks to a total of 2,880, divided among garrisons, service support, antiaircraft, and the steward’s branch. By the end of December 1946, this number had dropped to 2,238. In the spring of 1947, blacks were given a final choice: Either transfer to the steward’s branch or be discharged from the Corps. Some selected the latter course of action, but by September 1948, only 1,532 blacks remained in the Corps.

President Truman's Executive Order 9981 of July 1948 did little to change this policy. As late as May 1949, Marine Corps policy held that no black first-term enlistments would be accepted unless optioned for steward’s duty only. The Corps found it difficult to fill these special quotas. Marine Corps inducements were introduced to increase black participation, which included rapid promotions, guaranteed schooling, the closing of Montford Point, and the decision that all recruits would be trained at Parris Island. (However, they would be trained in separate units with black drill instructors.) These proffered inducements made little impression on the psyche of the black community.

In mid-1950, the North Koreans attacked across the demilitarized zone, and America was at war again. By 1951, the black Marine population increased some 400 percent, to a high of 8,001 enlisted men and three officers. Combat necessity caused integration to be carried out at such a rapid rate that by the summer of 1952, the Corps had disbanded the last of its black units. The Corps, the last service to integrate, became one of the first to eliminate overt segregation from its ranks.

This era is where my story begins. Overt segregation and racism were supposedly on the way out within the Marine Corps, but there were to be considerable bouts of pain and discomfiture in the coming years.

Though unaware of much that had gone before, I was aware of the 1948 Truman edict and assumed that the playing field was level. In late 1951, upon arriving in Pensacola, Florida, as a trusting 18-year-old eager to commence flight training, I discovered that such was not the case. Nor was I aware that I had taken the first steps along a twisted path that would lead to a three-star, 38-year career.

Once I found out what being a United States Marine was all about, jumping into the tiger’s jaw was just something to do. We’d been trained for combat. That’s our reason for being. When the time comes, hell, stick out your can. Let’s go. Let’s see what that old tiger’s got. Let’s jump right into his big, old jaw.

That’s what I was doing that day in Vietnam when that old tiger caterwauled and bit me. I was flying high. A lieutenant colonel. Marine fighter squadron commander. Keeper of the keys, Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 314. And to make it sweeter, our call sign was Black Knights. Hypothetical swords at the ready, I pulled that hot pad duty just like I wanted my men to do it. Five- to 12-hour stints, depending on the threat and the type of call for assistance.

Tiger growled. We listened. Marine troops pinned down, deep in the DMZ.

Twenty miles north of the Rock Pile, near An Khe. Target, 15 miles into North Vietnam. We fired up the Phantoms, those big, powerful, weirdly beautiful F-4s, and flew right into that old tiger’s jaw.

We took some pretty heavy fire on our first pass on target. I rolled in on my second pass, sing-songing Mk-84 500-pound bombs on top of some people on the ground. Although unfortunate, they weren’t passive. They nailed us with hot 37mm rapid fire as I pulled my nose up through the horizon. I felt the hit. The F-4 shuddered. . . .

For more information on General Peterson’s autobiography, click here.