Captain Laurance Safford is widely considered the Father of Naval Cryptology and his story is documented on the National Security Agency’s Hall of Honor. Captain Joseph Rochefort perhaps is even more famous for the codebreaking that helped win the Battle of Midway. These naval officers serve to remind us that there are sailors—cryptologists and cryptologic technicians—stationed around the globe as a part of the U.S. Tenth Fleet, whose mission is to execute the Navy’s signals intelligence (SIGINT), cyber, electronic warfare, and information operations capabilities. Less well known than Safford or Rochefort, however, is the group of enlisted sailors who became known as the “On-The-Roof Gang.” These sailors were the predecessors of today’s naval enlisted cryptologic professionals; their mission began in response to a period of dedicated expansion by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN).

Early Codebreaking Operations

At the end of World War I, wireless radio was a relatively new concept and the U.S. Navy radio intelligence (RI) capabilities—the ability to intercept and understand radio communications—were rudimentary at best. The Navy established a Code and Signal Section in the Department of Naval Communications in 1916, which primarily was interested in analyzing German ciphers during World War I. Navy personnel also were involved in a World War I effort to track German submarines by high-frequency direction finding (HFDF).1 These efforts ended with World War I in 1918, and the Navy transferred all RI activities to the U.S. Cipher Bureau.2

In 1921, agents from the Office of Naval Intelligence, FBI, and New York Police Department covertly obtained a copy of the “Imperial Japanese Navy Secret Operating Code—1918,” which belonged to a Japanese naval inspector visiting the Japanese Consulate in New York.3 This code, which became known as “The Red Book,” was photographed, page by page, and brought back to ONI for analysis and translation.4 The analysis revealed that the code would make it possible to decrypt the encoded IJN telegraphic messages sent between Japanese radio stations.5

Despite the potential intelligence gain through decryption of IJN messages, there were several obstacles to making it happen—the IJN code was only one facets of the intelligence problem. The United States first had to intercept these messages, something it did not have the capability to do. The Navy had no one trained in intercept operations, and the differences between the English and Japanese alphabet and Morse code made intercept efforts nearly impossible.

Recognizing the enormous potential intelligence gain, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral Charles Hughes suggested to Pacific Fleet commanders in 1923 that Navy radio operators listen for Japanese radio messages.6 Several highly motivated Navy and Marine Corps radio operators had some measure of success in this endeavor. One of those radio operators was Chief Radioman Harry Kidder, who was an amateur radio enthusiast and an expert radioman stationed in the Philippines. While performing his duties as a communicator, he noticed strong Morse code signals he did not understand. Because of the prevalence of the IJN in the Pacific and the CNO’s request to monitor Japanese communications, he assumed the code was Japanese and asked the wife of a friend to help him understand the code. She taught him the Japanese alphabet, katakana, which he began to copy regularly.7 Whether naval intelligence leaders in Washington were aware of Kidder’s accomplishments at the time is not clear; however, Kidder’s initiative and expertise at copying the katakana code paid enormous dividends in the years to follow.

Early intercept successes by these U.S. radio operators led some U.S. Asiatic Fleet commanders to look forward to the translated Japanese intercepts. However, these RI activities were conducted on an ad hoc and piecemeal basis, without any centralized direction.

In 1924, to deal with an increasing volume of Japanese intercepts, the Navy established a small office under the Code and Signal Section with the title of “Research Desk.” This Research Desk was given the designator OP-20-G, and a young Lieutenant Laurence Safford was selected as its first officer-in-charge. Safford immediately began to establish formal intercept stations in the Pacific that would permit OP-20-G to function, train personnel, and plan for future expansion.

The first dedicated intercept site was established at the U.S. consulate in Shanghai and designated Station ABLE in 1924. Other intercept sites were set up east of Honolulu (designated Station HYPO) in 1925, in the Philippines (Station CAST) in 1925, and Guam (Station BAKER) in 1927.8

On-the-Roof Gang is Born

In the Pacific, the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Asiatic Fleet (CINCAF), recognized the need for experienced intercept operators and drafted an official memorandum to the CNO in May 1928 detailing his need for the additional operators. Less than two months after the CINCAF memo, the CNO announced the Navy’s intention to formally train enlisted sailors and Marines in RI operations.9 At the time of this announcement, Harry Kidder was not only the best operator in the fleet, he also was local. He had been transferred to the Navy’s main communications station in Washington, D.C., for regular radioman (RM) duties.10 In the middle of this assignment, Kidder was selected to teach the first RI training class to ten hand-selected RMs.

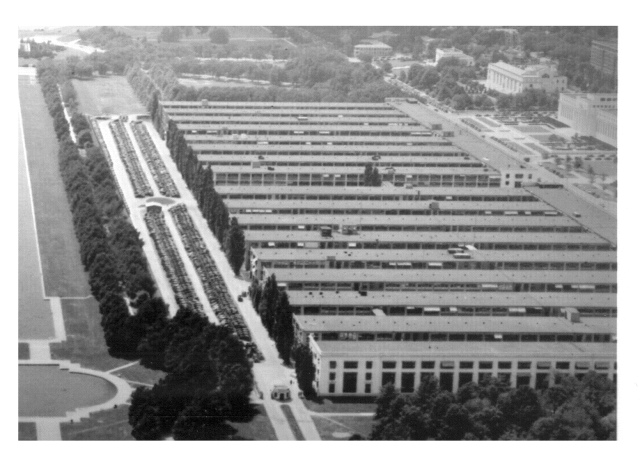

Partly for space concerns and partly for security, a steel-reinforced concrete classroom was constructed on the roof of the sixth wing of Main Navy building as a classroom for the new RI training, giving these cryptologic pioneers their name. Under the watchful eye of Chief Kidder, the classroom was designed to accommodate eight students and the radio intercept equipment necessary to conduct the training.

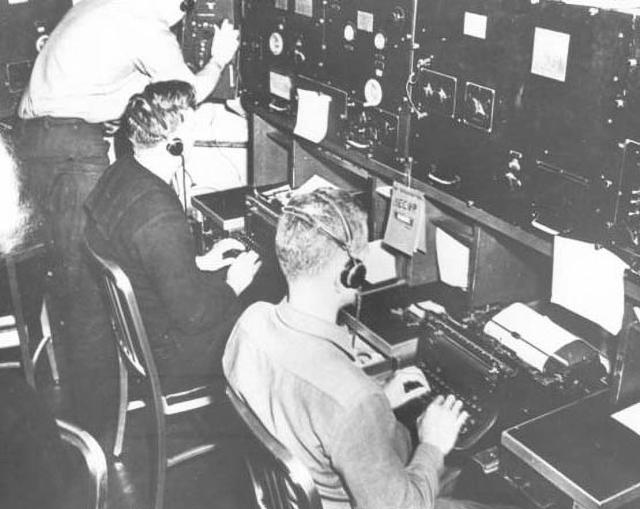

The training began with an overview of RI concepts, followed by an introduction into the IJN organization, order of battle, and communications procedures. The students were taught the Japanese alphabet, both katakana and the westernized rendering called Romaji, as well as Japanese katakana telegraphic code.11

Eventually, the copying of the Japanese telegraphic code was accomplished using a modified typewriter, designated by the Navy as RIP-5 and nicknamed the Underwood Code Machine.

Following the initial offering of the training, approximately two On-The-Roof Gang classes graduated each year, with each class consisting of three to ten radio operators. By October 1941, a total of 150 sailors and 26 Marines in 25 classes attended this new RI training on the roof of the Main Navy building.12

During the years of the On-The-Roof Gang training, tensions between the United States and Japan had continued to grow, and graduates were assigned to radio intercept sites around the Pacific. The eight graduates of Class #1 were sent to Station BAKER in 1929 to establish the radio intercept site there. Subsequent graduates were assigned to Station ABLE in China, Station HYPO in Hawaii, and the Station CAST in the Philippines, where they monitored the communications of Japanese ships at sea and shore stations.13

The reports prepared by personnel at these sites demonstrated both the tactical and strategic value of RI. Not only did these reports reflect the Japanese fleet's strategic capability to wage a comprehensive naval war against the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, but they also revealed Japan's intentions to invade Manchuria, to defend the western Pacific in case of a U.S. attempt to interfere, and to conduct electronic countermeasures in the event the United States attempted to monitor fleet communications.14 The intelligence gained through the intercept by the On-The-Roof Gang proved invaluable and was often the only source of information by which USN commanders had to make decisions.

World War II: Initial Japanese Attacks

Despite the growing RI efforts of the On-The-Roof Gang at naval intercept sites around the Pacific, direct warning of the impending Japanese strike against Pearl Harbor never came. A primary reason for this lack of warning was the changing of the IJN Operating Code in December 1940. The new operating code was designated JN-25B and had not been fully broken by 7 December 1941. Because of the changing codes, the only form of RI that appeared to offer relatively solid information about Japanese naval matters in the months prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor was traffic analysis—the process of deducing information from patterns in communication. For years, traffic analysts watched with precision the ships and squadrons of the Japanese fleet and their maneuvers. However, when the IJN Combined Fleet set out on its mission against Pearl Harbor, it went into a state of emissions control (EMCON), reducing its radio transmissions and fooling the traffic analysts into thinking the fleet remained in its home waters.15

Just hours after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Guam became a target of the IJN. Among other U.S. assets on Guam stood intercept Station BAKER, located at Libugon Hill. For three days, the seven assigned On-The-Roof Gang operators destroyed as much classified material as possible. On day three of the Japanese attack, more than 6,000 Japanese landed on Guam at Agat and Agana, and the United States. surrendered the island.16 The On-The-Roof Gang members were captured by the Japanese and held as prisoners of war in Japan until the end of the war.17

Almost simultaneously, Japan also targeted Navy assets on the Philippine. By January 1942, the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet, sent a message to CINCAF, recommending an evacuation of Station CAST personnel to Australia. The evacuations were conducted via three daring nighttime runs by the USS Seadragon (SS-194) and Permit (SS-178). As much equipment as possible was disassembled and brought on board the submarines for redeployment.

By 1942, Station CAST evacuees had merged with a processing unit of the Royal Australian Navy unit and reconstituted the site’s RI capabilities in Melbourne, Australia. The Melbourne RI site eventually became known as Fleet Radio Unit, Melbourne (FRUMEL), and was fully operational by summer 1942.18

Regaining the Intelligencer Advantage

For the six months immediately following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the IJN was indomitable. By March 1942, the Japanese had enjoyed a tremendous string of victories against the United States and the Allies in the Pacific. Having achieved almost most of its initial objectives ahead of schedule, Japan had momentum on its side. It had taken control of areas of Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific rich in natural resources, allowing access to the resources necessary for warfighting—rubber and oil. At the same time, Japan occupied strategic points surrounding those areas which would establish a strong defensive perimeter.19

The U.S. Navy was at a complete disadvantage strategically and tactically. Under these conditions, the role of intelligence became even more critical. The only hope the Navy had was an accurate estimate of Japan’s intentions. Unfortunately, most of the traditional sources of intelligence (reconnaissance, prisoner interrogations, and captured documents) had become more difficult to obtain.20 However, the newest intelligence discipline, RI, was still available, and the Navy counted on the On-The-Roof Gang to provide this intelligence.

Navy cryptanalysts at Station HYPO and OP-20-G made a breakthrough in the decryption of JN-25B in February 1942 and began to partially decrypt Japanese messages. It was clear to the On-The-Roof Gang intercept operators and analysts that the Japanese were preparing for operations near the U.S. base of Port Moresby. With decrypted and translated messages along with traffic analysis, the U.S. Navy was able to accurately determine the attacking force size, location, and composition. As the Battle of Coral Sea began, U.S. Navy warships were on station, ready for battle, in locations queued to them through RI.

The Battle of Coral Sea provided the U.S. Navy it first strategic, if not tactical, victory. By providing accurate and timely warnings of IJN intentions, RI conducted by the On-The-Roof Gang allowed the Navy to position scarce assets where they could interrupt and frustrate Japanese plans and intentions. RI also provided invaluable information concerning the Japanese timetable and order of battle for the invasion of Port Moresby up to the very eve of the battle. For the first time, RI had contributed directly to the conduct and the outcome of a major sea battle.21

As codebreakers had more and more success in breaking the JN-25B code, naval intercept sites were issuing intelligence reports with substantially decrypted text from intercepted IJN messages.22 The timing was good. Admiral Nimitz knew the Japanese were preparing for an attack, but he did not know where. In one of the JN-25B decrypts, naval analysts led by Joseph Rochefort famously reasoned that the Japanese had assigned the designator “AF” to Midway Island in their communications.23 Through careful decryption and analysis of intercepted IJN communications, Rochefort’s Fleet Radio Unit Pacific (FRUPAC) deduced almost all the information about the attack on Midway—everything from a planned diversionary attack on the Aleutian Islands to the estimated arrival times of the Japanese fleet at Midway.24

Using this information, the Pacific Fleet Intelligence Officer, Lieutenant Commander Edwin Layton reported to Admiral Nimitz that Japanese carriers would be located about 175 miles from Midway on 4 June 1942. Layton was quick to point out that the information he gave Nimitz was the result of the intelligence produced by the decrypted intercept from the On-The-Roof Gang and FRUPAC analysts.25 Radio intelligence in the form of intercepted, decrypted, and translated communications by the On-the-Roof Gang and Rochefort’s FRUPAC had provided Nimitz with a priceless advantage in a battle against a superior enemy—the element of surprise. RI had proven effective yet again, and the U.S. Navy’s victory at the Battle of Midway became the measuring stick for all SIGINT operations in the 21st century.

In exercising their new RI skills, the On-The-Roof Gang intercept operators became so skilled at their jobs, they began to recognize the Japanese radio operators’ “fists.” Each Japanese radio operator tapped out their code on their CW key with their own slight idiosyncrasies and skilled intercept operators could discern one radio operator from another.26 Through this skill and traffic analysis, it was known that Japanese Fleet Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect and leader of the attack on Pearl Harbor, was on the Pacific island of Rabaul in early April 1943. Although the callsign could not definitively be identified as Yamamoto, On-The-Roof Gang operators were able to identify the fist of Yamamoto’s communicator.27 In the early morning hours of 14 April, Station HYPO intercepted a Japanese naval message that detailed a travel itinerary and flight plan from the fist of this communicator. With the information provided by RI, the decision was made to target the plane. Yamamoto’s plane was shot down on 18 April, killing him and dealing a serious blow to the Japanese war effort.28

With the momentum from the Japanese in the Battles of Coral Sea and Midway, U.S. and Allied forces began to slowly take back territory from the Japanese. Supporting Allied warfighting all along, the On-The-Roof Gang became more and more proficient at RI, HFDF, and traffic analysis. Throughout the war, the intercept sites in Hawaii, Australia, and Bainbridge Island grew in both personnel strength and intercept capabilities. The Battles of Midway and Coral Sea reinforced the value of RI to Allied war planners, who continued to use RI intelligence through the end of the war.

On-The-Roof Gang operators, both at sea and ashore, participated in the victories in the Solomon Islands, Guadalcanal, Marianas Islands, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and more. They provided intelligence throughout the island-hopping campaign and the attrition of Japan.29 Radio intelligence had grown into an indispensable asset during World War II, and the 176 sailors and Marines that received the On-The-Roof Gang became the deckplate pioneers of modern naval cryptology and the predecessors of today’s U.S. Tenth Fleet.

1. National Security Agency (NSA) Center for Cryptologic History (CCH), “Navy Cryptology: The Early Years,” unpublished monograph, Pearl Harbor Publications.

2. Frederick D. Parker, NSA CCH, “Pearl Harbor Revisited: United States Navy Communications Intelligence, 1924–1941,” monograph CH-E32-94-01, 1994, 2-3.

3. CAPT Laurance F. Safford, USN. “A Brief History of Communications Intelligence in the United States,” NARA RG 457.2, SRH-149, 6–7 March 1952.

4, NSA CCH, “Early Japanese Systems,” unpublished monograph, Pearl Harbor Publications.

5. Laurance F. Safford, “History of Radio Intelligence: The Undeclared War,” NARA, Records of the NSA, RG 457, Records of the Predecessors of the NSA, RG 457.2, SRH-305, 15 November 1943, 35.

6. JO2 Thomas Leek, USN, “On the Roof Gang’: 55 Years of Silence,” All Hands, October 1983, 34.

7. Pearly L. Phillips, OTRG, “Kidder First OTRG Instructor,” Cryptolog (Summer 1983): 9.

8. Safford, “A Brief History of Communications Intelligence in the United States.”.

9. Chief of Naval Operation (CNO), Official Memorandum to Commander-in-Chief Battle Fleet, Command, Scouting Fleet, and Commander Control Force, “Training of radioman for radio intelligence work,” OP-20-G-X Serial #(SC) A6-2/A8, 16 July 1928.

10. Phillips, “Kidder First OTRG Instructor,” 9.

11. CAPT Duane L. Whitlock, USN, “On-The-Roof Gang” member (OTRG), “The Silent War Against the Japanese Navy,” Naval War College Review 48, no. 4 (Autumn 1995).

12. Carl A. Jensen, OTRG, “The Story of the On the Roof Gang (OTRG),” U.S. NCVA, NCVA History Book (Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing, 1996), 17.

13. Jensen, “The Story of the OTRG,” 17–18.

14. RADM Edwin T. Layton, USN and others, And I Was There: Pearl Harbor and Midway – Breaking the Secrets (New York: Morrow, 1985), 174.

15. David Kahn, “The Intelligence Failure of Pearl Harbor,” Foreign Affairs 70, no. 5 (Winter 1991/92): 147-48.

16. Graydon Lewis, “Guam: Some History,” Cryptolog 14, no. 5, Guam Special Issue (Fall 1993): 3.

17. Hal Joslin, OTRG, “Last Days on Guam . . . WWII as a POW,” Cryptolog 14, no. 5, Guam Special Issue (Fall 1993): 11.

18. Sidney A. Burnett, OTRG, “Adelaide River Station Northern Territory Commonwealth of Australia,” Cryptolog 5, no. 4 (Summer 1984): 10.

19. Henry F. Schorreck, “Battle of Midway 47 June 1942: The Role of COMINT in the Battle of Midway,” NARA, Records of the NSA, RG 457, Records of the Predecessors of the NSA, RG 457.2, SRH-230.”

20. Schorreck, “The Role of COMINT at Midway.”

21. Frederick D. Parker, NSA CCH, “A Priceless Advantage: U.S. Navy Communications Intelligence and the Battles of Coral Sea, Midway, and the Aleutians,” report CH-E32-93-01, 22–31.

22. Schorreck, “The Role of COMINT at Midway.”

23. Whitlock, “The Silent War.”

24. John Keegan, Intelligence in War: Knowledge of the Enemy from Napoleon to Al-Qaeda (London: Hutchinson, 2003), 234–36.

25. Layton, “And I Was There,” 57.

26. Duane Whitlock, OTRG, “They Too Never Got a Medal,” Cryptolog. 4, no. 4 (Spring 1983): 1.

27. Layton, “And I Was There,” 444.

28. Layton, 474–75.

29. Forrest R. Biard, “The Pacific War through the Eyes of Forrest R. “Tex” Biard,” Cryptology 10, no. 2 (Winter 1989).