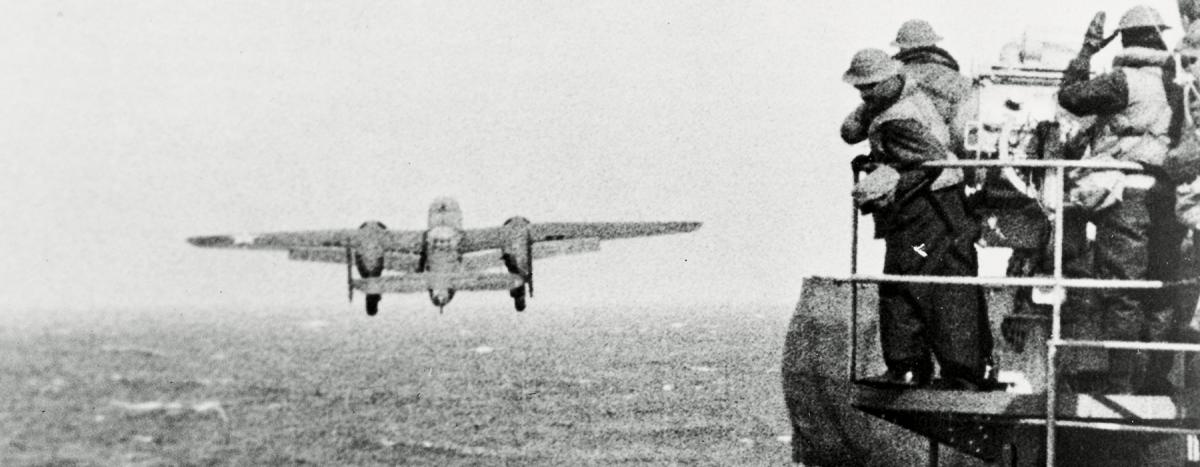

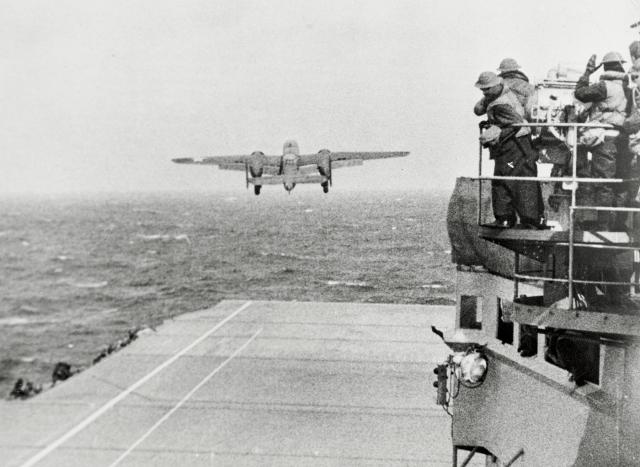

On 18 April 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle of the U.S. Army Air Forces entered the annals of World War II history in command of the celebrated Doolittle Raid, which took the war to Japan’s shores for the first time since the attack on Pearl Harbor. Having Army B-25s embarked on board the USS Hornet (CV-8) involved any number of challenges—but also embodied a spirit of interservice cooperation in America’s hour of need.

We did strictly dead reckoning, and we did not go in formation. We went in one at a time in line as we took off from the carrier. Some of the chaps did overtake each other and end up with maybe a couple or three airplanes together. The reason we did not fly in formation was twofold.

First, then the ones that were all first would have to wait for about an hour, and they’d use up an hour of gasoline waiting for the last one off. More important than that, you can fly individually using much less gas than when you fly in formation because, unless you’re the leader, in formation you’re continually jockeying. One airplane did form on me after we left Japan, flew all the way to the China coast with me.

At the time of the raid, we had been on the defensive, and the nation badly needed an offensive action. And so it was timely from that point of view. When I was given this job, I had top priority and complete control. The first thing I did was to find out which group had had the most experience in flying B-25s. The 17th Bombardment Group had had more experience than any other. And so I went to the 17th Group and asked for volunteers for a dangerous mission, not telling them what it was. And the entire group, including the group commander, volunteered.

So I got an operations officer and a deputy commander and turned over to them the selection of crews, and they, better than anyone else, knew the capabilities of each group. And so we picked over crews and selected 24. We were only going to use 16, so we had a 50-percent buffer to make sure that if anything happened to some of the crews, why, we would still have plenty. As a matter of fact, two of the crews cracked up in training—nobody hurt. They washed out their airplanes. That was on the short takeoffs.

When we went aboard the Hornet, there was perhaps just the least bit of coolness between the Navy people and the Army people. We felt a little out of place on a carrier, and they felt a little out of place having us there. But when we went under the San Francisco Bridge, over the radio said, “Hear ye, hear ye.” And everybody on board was told not exactly where we were going, not exactly what we were going to do, but that this was a mission against Japan. From then on, there was complete rapport.

As a matter of fact, the Tokyo fliers were given the best of everything. If they were rooming with a chap, he gave him the best place in the room. Captain Marc Mitscher, commanding officer of the Hornet, gave me his quarters. After that first “Hear ye, hear ye,” there was complete and utter cooperation at every level.

We had quite a sea when we launched. Then there was overcast until we got almost to Japan. And when we got almost to Japan, the weather cleared up. That was the time when we would have liked to have been obscured a little bit. Then when we left Japan, we found that we had a pretty strong headwind, and we got, I guess, halfway to China before the wind abated and then turned around and gave us a tailwind for the rest of the way in.

Of the 80 men in the 16 aircraft, 73 survived the mission. One was killed when he jumped in his parachute. Two were drowned when they landed off the shore of China in the water. Eight were taken prisoner by the Japanese, and of those eight, three were executed, and one died of beri-beri and malnutrition in a Japanese prison.

To learn more about the U.S. Naval Institute Oral History Program, visit the program’s webpage at usni.org/archives/oral-histories.