In October 1944, I was with Marine Scout Bomber Squadron (VMSB) 142 stationed on Emirau Island, 1 degree south of the equator, in the northern Solomons. We were part of the force keeping the Japanese bases of Kavieng and Rabaul isolated. Training flights in our Douglas SBD Dauntlesses plus an occasional strike was the order of the day, as we waited for the Philippine liberation campaign to begin.

I had noticed a small growth on the sole of my left foot that made it painful to walk on, and also painful to put pressure on the rudder pedal of the plane. After a couple of weeks, I went to see Bernie Coan, USNR, our squadron doctor. He was just out of medical school, and after examining my foot declared that I should go to a naval hospital and have the growth removed. He found that the nearest hospital was on Manus. That was the beginning of a saga.

Manus, with a huge naval base, was in the Admiralty Islands, some 125 miles west of Emirau. Dr. Coan put in a request to send a patient (me) over to the naval hospital there, and we waited, seemingly for weeks, for clearance. Who knows what route that request took? Probably down to 1st Marine Air Wing headquarters and from there to Pearl Harbor and back. Meanwhile, I limped around and flew with my foot in an awkward position on the rudder pedal. I had nearly given up when the clearance finally arrived.

Standard practice in that area forbade a single-engine plane to make an over-water flight of that length, so two SBDs were cleared to go. Lieutenant Guy McKee flew the second Dauntless and took the doctor in his rear seat. The rudimentary charts we had of Los Negros and Manus showed several airstrips. We had no idea which one we should head for or where the naval hospital was located. I randomly picked the Mokareng field, got permission to land, and walked over to the control tower to seek information. We found that the hospital was on a part of Manus separated from Los Negros by a swampy area, and no roads existed between the two. There was a small ferry boat service that ran on a regular schedule, and we were directed to a landing.

To our dismay, the landing was three or four miles from our airstrip, so we set out on foot. At that time, any vehicle picked up anyone walking, so we soon got a ride to the boat. It was an LCVP, or Higgins boat, running on a schedule that included stops at a dozen landings around the perimeter of Manus Harbor. The route was so extensive it took an hour to make the circuit. We debarked at a place within a half mile of the hospital. Once there, the doctor found the appropriate department, and soon a gray-haired commander came to look at my problem.

After just one glance, he said in a tone that I thought was contempt: “Why, that’s just a plantar wart; get some medication from the pharmacy, dose the main growth for a couple of weeks, and its satellites will die. You can then pare out the center one.” Somewhat abashed, we went to the pharmacy and came away with a jar of the named ointment. After all the “to do” about clearances and flying two planes 125 miles, the hospital visit took 15 minutes.

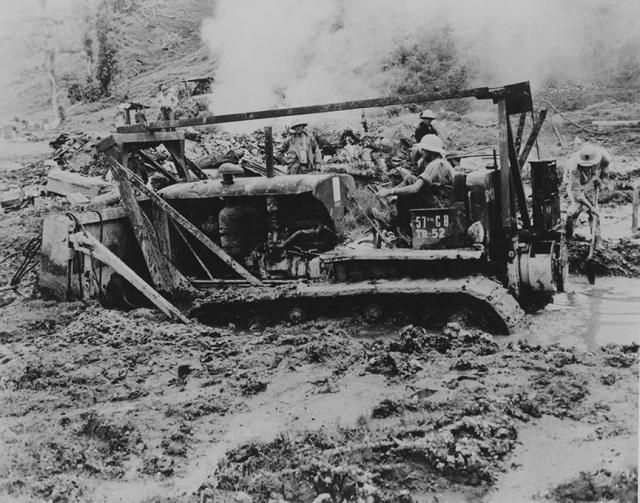

Having concluded our business with time to spare, Guy suggested we look up his brother, John, a chief in a Seabee unit. Again, we asked directions, hitched a ride, and found Chief John McKee in an area of extensive docks, with large cranes, trucks, and heavy equipment. Back in Alabama, John had worked with a large steel construction company. Too old for the draft, the Seabees were very quick to latch onto him and soon made him head of a stevedore unit. When the U.S. Army invaded Los Negros, John’s boys went in with big bulldozers and charged through the Japanese defenses. After things settled down, the Navy established a giant fleet anchorage on Sea Adler Harbor, thence known as “Manus.” From there, many of the subsequent amphibious assaults were launched. The base included everything from floating dry docks to airfields, from heavy ordnance depots to major ship and aircraft repair shops, from large troop accommodations to Coca Cola bottling plants!

Amid all that action, John and his fellow chiefs got the port operation running. They unloaded a constant stream of cargo ships, stowed the contents in warehouses or “dumps,” and loaded everything imaginable on to combat ships when called for. Once all that was running smoothly, the chiefs set themselves up in “decent” living quarters. Having access to virtually anything in the way of equipment and supplies, they erected small Quonset huts, each with a spacious lounge area plus rooms for two. There was a recreation hut with a pool table, a ping-pong table, dart board, music system, and bar. The largest unit consisted of a galley with attached reefer, and an adjoining dining room. The latter was equipped with tables for four covered with tablecloths and set with Navy silver and china. The contrast between their quarters and the primitive tents and mess we had on Emirau was startling.

It was a happy reunion for the McKee brothers, the first since California a year earlier. John suggested that the three of us stay for a good dinner, spend the night, and return to Emirau in the morning. That was agreeable to all. At dinner we were asked if we preferred steak or turkey for the entrée. Apparently that reefer was kept well stocked! There seemed to be plenty of alcohol available, too. Guy asked his brother if there was some place he could buy a few cans of beer to take home. John replied: “Sure. How much do you want?” Guy, not wanting to be piggish, thought maybe a case. (The beer ration on Emirau was two cans per man per week.) John gave him a funny look and asked, “How much can you carry in those planes of yours?”

Finding that he was serious, we started thinking of how much we could stuff in. An SBD is not much of a baggage carrier. Cases of anything would not fit very well. Since one rear seat was empty, we guessed that four or five cases would fit if we could tie them down somehow. Maybe another case in individual cans might work. John said he’d bring some down to the boat landing in the morning. True to his word, there was an enormous quantity of beer at the dock. Cases were stuffed in sea bags, individual cans in laundry bags. We dragged it all aboard the LCVP while the coxswain eyed us unhappily. At every landing, passengers looked at us with suspicion; the cans clinked as we dragged the bags around to make room.

At last at our destination, we unloaded our burdens on the wharf and pulled them out to the road, sweating heavily. We still had four miles to go to the airstrip. How could we hitch a ride with all this gear? Presently, to our relief, an Army truck driven by a corporal stopped for us. Guy asked him if he’d like a case of beer. The corporal was a little suspicious but said he guessed he would. “Well,” said Guy, “let’s throw all these bags in your truck, you drive us over to the Mokareng airstrip, and a case is yours.” That deal was struck and carried out.

The next workout was to hoist all that cargo onto the wings and stow it down in the cockpits, somehow leaving room for the pilots plus the doctor. The empty rear seat helped. We got some of the cases of beer down in the bilges, under the seats, on the floors, and somehow lashed it in place. That tropical sun was doing a job on us, and there was one more major strenuous effort: to start those Wright engines.

The SBDs were holdovers from the days of hand-cranked inertia starters. Normally, two ground crewmen would swing the crank, while the pilot sat in the cockpit ready to engage the engine. In our case, one of us had to help the doctor crank, then run around the wing, climb in the cockpit, and pull the toggles, hoping to catch the engine before having to climb down and start over. Eventually, we got them going.

On arrival at Emirau, we were greeted with mild curiosity until Guy reached down in the cockpit and passed his crew chief a can of beer, well chilled during its transit across the Bismarck Sea. Word of our cargo spread rapidly, and we became instant celebrities, though that distinction was short-lived. In the future, other trips to Manus were arranged, and I’m sure Douglas engineers would have been amazed at the sight of their sturdy dive bombers turning into flying beer trucks. My expedition with my wart was my only foray into that trade.

As for the wart, after treating it for two weeks with the salve we had procured, all pain seemed to be gone. I went to see the doc and asked his opinion. He poke at it with a scalpel, asked if I could feel anything. I replied that I could not. He poked some more with the same results and opined that it was dead. With that he handed me the scalpel and said, “Oh hell, you pare it out!” I did.