If there were a contest to find the U.S. Navy ship with the shortest career from commissioning to sinking, the USS Lakatoi, with just six days, would certainly be a serious competitor. Her career was so brief the vessel never received a hull number. I would never have heard about the ship if not asked to find out the truth behind a “sea story.” The tale began with an improbable premise: a U.S. Navy midshipman assigned to duty at Guadalcanal during the desperate days of 1942.

After extensive research, I found two of the four officers of the Lakatoi, a commissioned vessel of the U.S. Navy, were midshipmen. I, and others among the more than 50 men who served as midshipmen in 1941 and 1942, believe the four "mids" were the first serve in that or any capacity on board a U.S. Navy ship in nearly 100 years.

The story of USS Lakatoi and her midshipmen begins on 16 December 1941, when Midshipmen Edward S. Davis and Robert H. Dudley, USNR, reported aboard the USS George F. Elliott (AP-13) at the Norfolk Navy Yard. The Elliott operated for the next six months as a general troop transport in the Atlantic and Pacific. The ship’s assignment changed on 5 June 1942 when she started loading Marines and their equipment for the 7 August 1942 amphibious assault on Guadalcanal.

According to Dudley’s report to the Supervisor of the U.S. Merchant Marine Cadet Corps, on 7 August he was one of the George F. Elliott’s boat wave officers for the landings. The next day, he remained behind as the officer in charge of one of the ship’s 3-inch antiaircraft guns. In that day’s air attack, a Japanese plane hit by the ship’s antiaircraft guns crashed onto the Elliott. After hours of futile attempts, the uncontrollable fires forced the crew to abandon ship. Most were rescued by the USS Hunter Liggett (AP-27). On boarding the Hunter Liggett, Davis and Dudley joined their classmates Midshipmen Joseph W. Coleman and John J. Hagerty. Ordered to withdraw to Noumea, New Caledonia, with the rest of the amphibious force, the Hunter Liggett, with George F. Elliott’s survivors, arrived there on 13 August 1942.

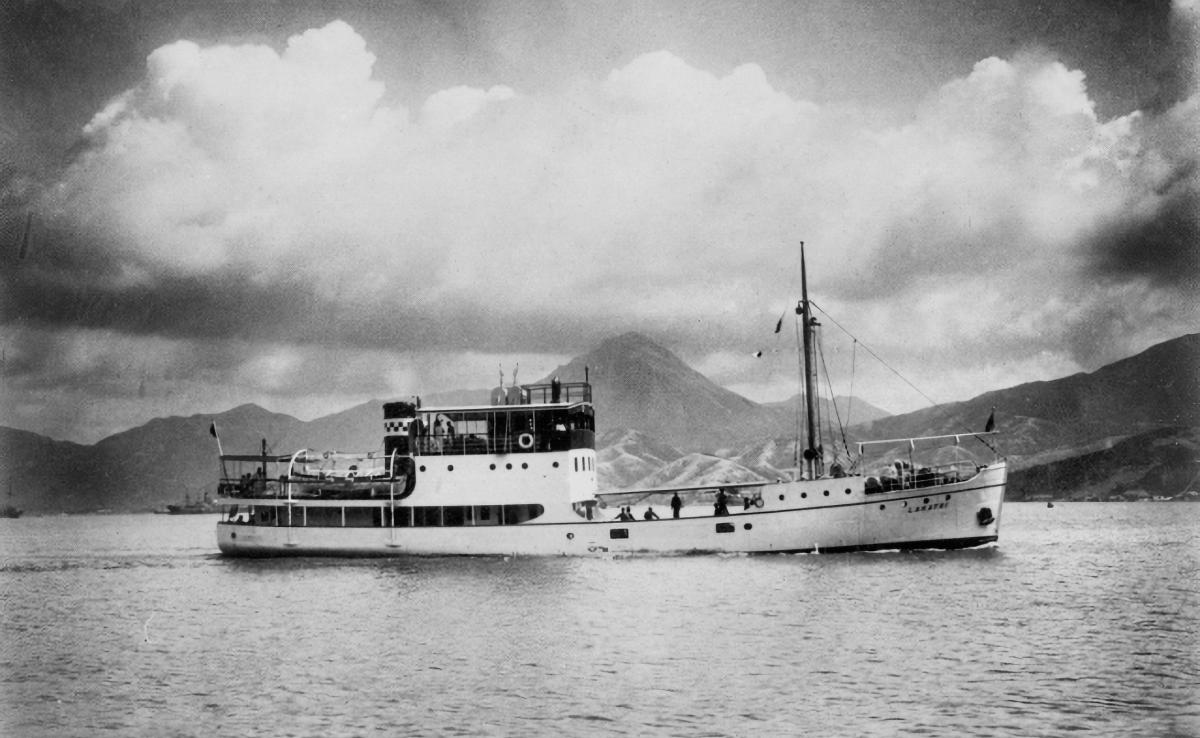

The evacuation of amphibious shipping left the Marines ashore short on supplies, especially food and ammunition. With the transports unable to return to Guadalcanal to finish discharging without a strong escort, an urgent need existed to resupply the Marines using stealthier means. One option was for smaller ships, operating without escort, to sneak in and out under cover of darkness. The test ship for this assignment was the roughly 130-foof inter-island freighter M/V Lakatoi. However, the Navy believed the Lakatoi was sufficiently “ocean going” to undertake a mission that can only be described as one of utter desperation. The ship, crewed by volunteers, was expected to sail through roughly 1,500 miles of enemy-controlled waters without being detected—and then sail back through the same waters so that they could repeat the mission.

The Navy1 requested the indefinite loan of the vessel from the Army on 14 August with the stated intention of replacing her civilian crew with Navy personnel. The following day, the Lakatoi was commissioned, with Lieutenant Commander James Ian MacPherson, USNR, in command. MacPherson, formerly the Elliott’s navigator, was an experienced merchant mariner. He selected the Lakatoi’s crew from among the Elliott’s survivors and the crew of the USS McCawley (AP-10). For his bridge officers, he selected Midshipmen Davis and Dudley. Warrant Machinist Edwin Murdock was the Lakatoi’s engineering officer.

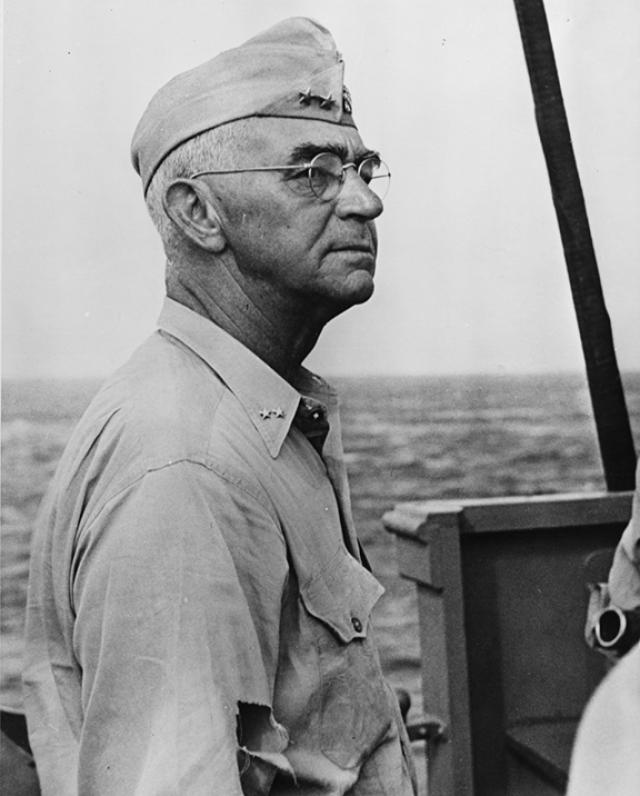

On the afternoon of Monday, 17 August 1942, the USS Lakatoi moored on the port side of Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner’s2 flagship, the McCawley, to make final preparations for her mission. Befitting the desperate nature of the enterprise, Admiral Turner personally inspected the Lakatoi with his staff. Thus, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that Turner not only knew the ship’s crew included the two midshipmen, but personally met Davis and Dudley. Further, the admiral was in frequent contact with their classmate, Midshipman Gordon R. Williams, who at the time was assigned to his flagship.

After his inspection, Turner ordered the removal of some of the Lakatoi’s topside weight and replacement of her .30-caliber machine guns with two .50-caliber guns. Ultimately, the most important change he ordered was likely an afterthought: the addition of two rubber life rafts to augment the Lakatoi’s lifeboats. Turner then ordered MacPherson to get the Lakatoi under way for Tulagi at 0800 19 August 1942. MacPherson was to use a circuitous route3 and to arrive at the southern Solomon island at day break on 25 August. On arrival, he would have just 12 hours to discharge the Lakatoi’s cargo and sail for Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides. If the ship could not make this schedule, she was to remain more than 250 miles from Tulagi and try again the next day. In keeping with the stealthy mission, MacPherson was ordered to maintain radio silence while listening for warnings transmitted to him by the Marines on Guadalcanal.

However, whatever Admiral Turner ordered be removed from the Lakatoi’s topsides, it did not include the cement slabs that had been previously placed around and on top of the wheelhouse and radio room as a form of “armor.” The Lakatoi’s civilian crew warned MacPherson that the ship rolled heavily, with the well deck forward being continually awash when the vessel was fully loaded to her maximum 9 foot draft. MacPherson reported he had loaded the Lakatoi in accordance with the available stability information, which would not have taken into account the concrete slabs. So, despite MacPherson believing the ship was properly loaded, her stability was probably impaired when all the cargo was loaded.

The Lakatoi got under way as ordered and cleared the Noumea Harbor entrance two and a half hours later. On departure, McPherson reported making 10 knots in force 5 (17 to 21 knots) winds from the southeast. However, by that afternoon things were no longer going according to plan. The ship was making three-quarters of its planned speed and rolling heavily. MacPherson’s description of the Lakatoi’s motion was ominous: “During this period vessel was rolling from 15 to 20 degrees continually, the roll period being quick but with a sluggish recovery at the end of the roll, the lee side of the well deck being continually full of water.”

On 21 August, less than a week after commissioning, MacPherson reported that the Lakatoi was laboring in gale-force winds, very rough seas and a heavy southerly swell. Shortly after noon, the ship lost her port lifeboat. MacPherson reported he put the wind and sea on the ship’s starboard quarter in an attempt to reduce rolling. These efforts proved to be fruitless. At 1305, a heavy sea struck the vessel on the port side, causing her to immediately list heavily to port and to sheer off to the left. Within two minutes, the Lakatoi broached and then capsized roughly 400 miles north of New Caledonia.4

Despite the rapid sinking, none of the crew were lost, although several were injured. Distributed among the life boat and the two rubber rafts the 29 survivors found very limited provisions.5 Because the ship sank so fast, MacPherson and the midshipmen had only the lifeboat’s compass, the sun, and stars to navigate by. One of the survivors, Coxswain John L. “Jack” Scovil, who kept a detailed log of the voyage, wrote on 25 August: “We hoped and prayed to hit New Caledonia. I was thinking of Captain Bly [Bligh] and Mutiny on the Bounty and hoped Captain MacPherson knew as much as he did.”

The gale in which the Lakatoi foundered was so intense it kept the survivors adrift for more than two days. Finally, on the morning of 24 August the wind and seas moderated. MacPherson ordered the lifeboat’s sails set and steered in the general direction of New Caledonia, towing the unwieldy rafts.

Over the next week, the survivors sailed when they could and, when not, rowed on a southerly course. They reported freezing cold at night, broiling sun during the day, and starvation rations throughout. Both MacPherson and Scovil reported a PBY patrol plane flew by them on 27 August, roughly a quarter mile away at 500 feet. However, the plane apparently did not see them, so no report was made. On 31 August, just hours before sighting the north coast of New Caledonia, one survivor died of exhaustion and exposure. Around midnight, the lifeboat with its two rafts crossed a coral reef and anchored for the night before trying to land on the beach in daylight. MacPherson reported he issued the last of the water, one ounce per man, and that in his opinion the rafts would not have lasted another day. The survivors finally set foot ashore at Passe d’Amos, about five mile east of Pam Head on the northeast coast of New Caledonia around 1030 on 2 September, after nearly two weeks at sea.

MacPherson sent the three most physically able crew members to find help, while the rest of the survivors searched for food and water. Around 1400, two of the three survivors returned with a local farmer who brought them a bucket of fresh water. The other sailor was taken by the farmer’s son to make contact with the U.S. Army’s beach patrol. Three hours later, Army doctors and medics from the Second Field Hospital arrived to assist the survivors. Four of the survivors were evacuated by motor launch because of their debilitated state, while the other 24 were evacuated by land.

The survivors remained at the Second Field Hospital until 16 September, when they boarded the USS Solace (AH-5). As the Lakatoi’s survivors suffered the loss of two ships within a very short period of time, Admiral Turner recommended they return to the United States. Most did so on board the USS Wharton (AP-7). However, the two midshipmen had left a few days earlier on board a civilian passenger ship chartered to the Navy, the MS Brastagi. In his endorsement of Lieutenant Commander MacPherson’s report on the loss of the Lakatoi, Vice Admiral William F. Halsey wrote, “The Commanding Officer and members of the crew of the U.S.S. Lakatoi displayed fortitude and heroism in keeping with the best traditions of the service.”

A month after walking ashore on New Caledonia, six of the Lakatoi’s crew, including MacPherson, Machinist Murdock, and four sailors were awarded the Navy and Marine Corps medal for their heroism. Scovil summarized their experience by concluding his log, “It sure was an experience, but I don’t want any more of it.”

1. Commander, South Pacific Force, then Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, USN

2. Commander Amphibious Force, South Pacific

3. USS Lakatoi was to follow the following track, starting with point AFFIRM. AFFIRM, 21o 30'S 168o 15' E; BAKER, 17o 48'S 167o 40'E; CAST, 13o 00'S 165o 00'E; Dog 10o 00'S 162o 00'E

4. 18o 55'S, 167o 40'E

5. Four (4) gallons of water, 20 pounds of “hard tack”, six pounds of chocolate, 1200 “Horlock Thirst Tablets”, six 1-gallon cans of tomatoes and twenty 12oz cans of peaches in syrup.

![Jack-Scovil-Typed-Dairy-P2_21[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/embed_medium/public/navalhistory/Jack-Scovil-Typed-Dairy-P2_211.jpg?itok=aE0KT0yC)