The Demologos, launched in 1815 and later renamed the Fulton after her creator, Robert Fulton, was the first steam-powered vessel in the U.S. Navy. The unique floating battery almost did not receive that distinction. Only a matter of months earlier, Master Commandant Thomas Macdonough came close to bringing a steam-powered warship to the most decisive battle of the War of 1812.

The United States and Great Britain had been at war since June 1812, and Napoleon’s defeat in April 1814 brought thousands of experienced soldiers to Canada. The War of 1812 began as a sideshow to the British government, but now it had their military’s undivided attention. That summer, Governor in Chief of British North America Sir George Prévost assembled the largest army in North America to date. After Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry’s victory at Lake Erie the previous fall, Lake Champlain was the most likely route for a British invasion.

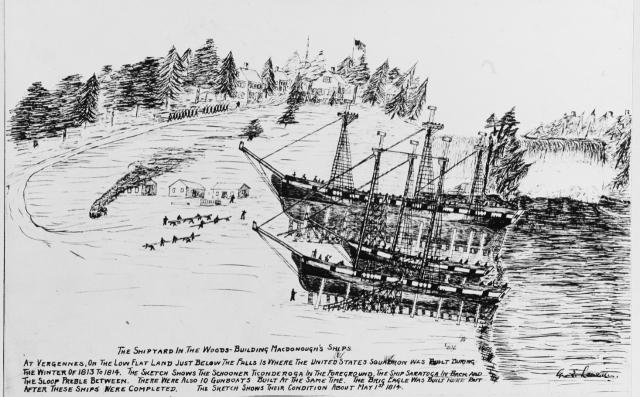

Master Commandant Macdonough had commanded the U.S. Navy on Lake Champlain since September 1812, and in the spring of 1814, he desperately needed ships. He and his British counterpart, Commander Daniel Pring, engaged in a shipbuilding race to control the lake. Macdonough had excellent shipwrights and carpenters building and repairing his little fleet. The British used the St Lawrence River to ferry materials, supplies, ordnance, and sometimes entire galleys to their base at Isle aux Noix. In February 1814, Secretary of the Navy William Jones authorized Macdonough to purchase a steamboat under construction near Vergennes, Vermont, if he deemed it necessary.1 A steamboat could be an incredible asset on a narrow lake such as Champlain. Steamboats are not limited by wind and current like a sailing vessel. In fact, a steamboat could tow many of the galleys or other vessels if necessary. A steam engine also requires fewer men to work the machinery than it does to manage sails. New York Governor D. Tompkins assured Secretary Jones that the Lake Champlain Steamboat Company has “an Engine & machinery ready for her equipment at Vergennes” and that “She may be made a most formidable & efficient Vessel of war.”2

Convinced of the merits of the steamboat, Secretary Jones campaigned for Macdonough to purchase the vessel. He envisioned the vessel cruising the lake and adjoining rivers undeterred with a bulwark protecting the engine and cannons manned on a covered gun deck.3 The vision in Washington, however, did not match the reality at Lake Champlain. Macdonough reported to Secretary Jones that his shipwrights assured him the steamboat “cannot be done within two months; owing to the Machinery not being complete, and none of it being here.”4 His shipwrights could build entire ships in that amount of time. Forty days before launching the corvette Saratoga and 19 before the brig Eagle, they were still trees firmly planted in the Adirondack wilderness. Macdonough also worried about the “extream liability of the Machinery (composed of so many parts) getting out of order, and no spare parts to replace.5 He needed another ship to arm, so he purchased the steamboat, but chose to rig her as a schooner.

The former steamer, now named Ticonderoga, relaunched on 12 May 1814. The schooner was 120 feet long and about 350 tons. She had a narrow beam for her length to accommodate for the side-wheels that were never installed. She was also almost flat-bottomed to navigate the various shoal waters of the lake. Macdonough armed and manned the Ticonderoga with ordnance, with crews cannibalizing two poor-sailing sloops and four old galleys. The schooner carried eight 12-pounder and four 18-pounder long guns, and five 32-pounder carronades.6 Macdonough placed a trusted junior lieutenant, Stephen Cassin, in command. When the Ticonderoga joined the Saratoga, the sloop Preble, and several gunboats in blocking the British squadron from entering the lake, Macdonough reported to Secretary Jones, “the Schooner is also a fine Vessel & bears her metal full as well as was expected.”7

The British were building a 39-gun frigate, HMS Confiance. Her completion would make Macdonough’s position untenable. After completing construction on the brig Eagle, Macdonough assembled his squadron at Plattsburgh Bay to await the British attack. The British squadron, now under the command of Captain George Downie, arrived the morning of 11 September 1814. The subsequent battle's main action was between Macdonough’s flagship, the corvette Saratoga, and the British frigate Confiance, but the Ticonderoga also “gallantly sustained her full share of the Action.”8 She beat back several boarding attempts by British gunboats with grapeshot from her carronades. The schooner then crippled and forced aground the sloop HMS Finch. The battle ended with a British surrender after a little more than two hours of fighting. The British defeat halted Governor-General Prévost’s invasion and secured the United States’ northern border for the remainder of the war. The victory cost the Ticonderoga six dead and six wounded.9

Macdonough emphasized speed of construction over the chance of longevity when he built his squadron. After fulfilling their purpose by removing the British from Lake Champlain, they were laid up at Whitehall, New York, immediately after the war. By 1820, the Ticonderoga, like many of the other ships, decayed and sank at anchor. The government auctioned off the wreck to salvagers in 1825. The city of Whitehall raised the remains of the hull in 1959 for a bicentennial celebration. They currently reside on display at the Skenesborough Museum.10

Macdonough had named the schooner for the British fort taken by General Ethan Allen during the American Revolution.The Ticonderoga’s legacy continues with four more U.S. Navy vessels sharing the name, including the famous World War II aircraft carrier and the current class of guided-missile cruisers. The original, however, embodies the meaning of ticonderoga—Iroquois for “between two lakes”—the most. The U.S. Navy spent the next several generations transitioning from a sail-powered to steam-powered navy, and the original Ticonderoga was the first to be “between.”

1. Secretary William Jones to Master Commandant Thomas Macdonough, February 22, 1814, in William S. Dudley and Michael J. Crawford, eds., The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History. 3 vols. (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1985), 3:396–97.

2. Governor Daniel D. Tompkins to Jones, March 10, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:398–99.

3. Jones to Macdonough, April 20, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:428–29

4. Macdonough to Jones, April 30, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:429–31.

5. Macdonough to Jones, April 30, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:429–31.

6. Macdonough to Jones, April 30, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:429–31; Howard Chapelle, American Sailing Navy (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1949), 298.

7. Macdonough to Jones, May 29, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:505.

8. Macdonough to Jones, September 13, 1814, in Dudley and Crawford, The Naval War of 1812, 3:614–15.

9. David Curtis Skaggs, Thomas Macdonough: Master of Command in the Early U.S. Navy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2003), 130–34, 143.

10. Kevin J. Chrisman and Arthur B. Cohn, “Lake Champlain Nautical Archaeology Since 1980,” The Journal of Vermont Archaeology: The Vermont Archaeological Society Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Issue, vol. 1, (1994): 159–60.